The White Queen finishes airing in the UK on Sunday, and so I can resume non Plantagenet blogging, while wondering how on earth they are going to fit so much of the final year of Richard III including the deaths of his son, wife, an alleged affair with his niece and the battle of Bosworth in an hour long episode?

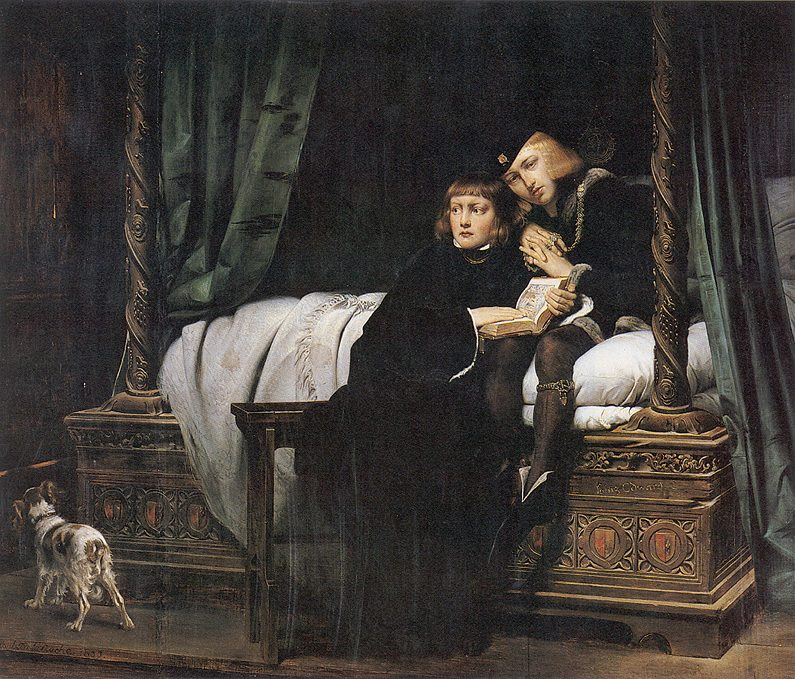

In the last episode we saw the deaths of the princes in the tower; Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, at the orders of Margaret Beaufort and the hand of the Duke of Buckingham. Since then I have had a couple of emails asking me if Margaret Beaufort killed the princes, why do so many people still think Richard did it? Welcome to the world of historical fiction.

Truth be told, we don’t know who killed the princes in the tower and we likely never will. Richard is considered the most likely suspect, as the bulk of evidence points towards his hand in it. Assuming of course, the boys were murdered, which in itself is speculation.

The Facts

On the 14th April 1483, Edward IV died. His eldest son, the twelve year old, Edward, the Prince of Wales, was at the time presiding over his court at Ludlow. Upon hearing the news, he and members of his household, including his uncle Anthony, Earl Rivers and his half brother, Richard Grey.

Upon King Edward’s death, he named his brother Richard of Gloucester as his son’s Protector. Richard then left London and met the young king on his way. Richard dismissed the boy’s household and had Earl Rivers and Richard Grey arrested, despite Edward’s protestations. Richard then escorted the boy to the Tower of London where he was to wait for his coronation. On the 16th June Richard had Edward’s nine year old brother; Richard, Duke of York, join him there from sanctuary, where he had been in hiding with his mother.

The coronation, however, never came. On the 22nd June a sermon was preached declaring that Edward IV had been pre-contracted, if not married, to Lady Eleanor Butler, rendering Edward’s marriage to Elizabeth Woodville and their resulting children illegitimate. Three days later Parliament asked Richard to assume the throne. A day later on the 26th June Richard became king.

The boys remained in the Tower, where they were seen occasionally playing together in the grounds. Over the summer of 1485, however, the sightings of them became less and less until their final sighting in August. The most common explanation is that they were murdered shortly afterwards. Rumours spread through England that the princes were dead and contemporary sources agree that by the end of the year, their death had become accepted common knowledge.

In 1674, during the reign of King Charles II, the Tower of London was remodeled. Workmen discovered the skeletal remains of two children hidden under a stair. The bones were placed in an urn designed by Sir Christopher Wren and put into a wall of Henry VII’s Lady Chapel at Westminster Abbey, with the following inscription:

“Below here lie interred the remains of Edward V , King of England, and of Richard, Duke of York. Their uncle, Richard, who usurped the crown, imprisoned them in the Tower of London, smothered them with pillows, and ordered them to be dishonorably and secretly buried. Their long desired and much sought after bones were identified by most certain indications when, after an interval of over a hundred and ninety years, found deeply buried under the rubbish of the stairs that led up into the chapel of the White Tower, on the 17th July, 1674 A.D. Charles II, most merciful prince, having compassion on their unhappy fate, performed the funeral rights of these unfortunate princes among the tombs of their ancestors, A.D. 1678, the thirtieth year of his reign.”

Later examinations of the bones revealed that the larger of the two was probably aged between 11 and 13 and the younger between 7 and 11. No further examinations have been made to carbon date the bones or to determine the gender. While the recent positive DNA testing of a skeleton revealed to be Richard III could potentially identify the bones as the princes, it is unlikely that this will actually occur. Westminster Abbey and the royal family have repeatedly denied requests to examine the bones over the years. The princes are not the only remains thought to be suspect and the Abbey apparently wants to avoid setting a precedent for testing the questionable burials. On top of this, a positive identification would not actually indicate how they were killed nor who killed them, while a negative identification would raise far more questions.

In the eighteenth century, workmen working in St. George’s Chapel in Windsor discovered two coffins buried with Edward IV, they were assumed to be the bodies of his children who predeceased him; a daughter Mary and a son George. Twenty years later two coffins were found clearly bearing the names of Edward’s children Mary and George, but no attempt was made to identify any of the remains.

The Suspects

Richard III

If the boys were murdered there are surprisingly few suspects, though Richard III is considered by many historians to have been the most likely culprit:

- It was through his actions that Edward and Richard came to the tower and while there they were in his custody, guarded by his men. It was Richard III who placed Edward in the Tower and then had his brother join him. However, it was also traditional for kings to reside in the Tower before their coronations, and his instructions for Richard to join him, may have been to provide companionship for his nephew.

- Richard III’s actions were, in themselves, suspect. He had dismissed Edward’s household and did not provide a new one for him while he was in the Tower. Richard put the coronation off numerous times, but this suggests that he was planning to usurp the throne, not necessarily murder the boys.

- While the princes were alive, Richard’s claim to the throne was tenuous. Rebellion could, and did, rise up easily, centred on deposing Richard in favour of Edward, until it was believed that they were dead.

- After the princes disappeared Richard did nothing to disprove the rumours that they were dead. As they were in his custody, it would have been in his interests to bring them out of the Tower. As he did not, it stands to reason that he knew they were missing. Further, during his two year reign, he did not launch any investigation into their disappearances or prosecute anyone for their murder.

- During Henry VII’s reign a Yorkist soldier, James Tyrrel, admitted to murdering the princes under Richard’s orders. However this confession was extracted under torture, and there is no surviving evidence regarding it, except a reference to it by Thomas More.

Henry VII/Margaret Beaufort

- Henry could not have ascended to the throne if the two princes had been alive.

- Henry was at the time of their disappearance, in Brittany. He could not have personally been involved but his mother, who managed his support in England on his behalf, may have given orders to advance his claim.

- Margaret Beaufort had spent a great deal of time and energy creating a support base for her son’s claim, however her efforts only garnered real support after the princes were considered death. This was partly because people were more receptive to Henry’s cause knowing only Richard stood in its way, and also because Margaret herself redoubled her efforts, suggesting that she knew beyond reasonable doubt that the princes were dead.

- Initially Elizabeth Woodville arranged the marriage between her eldest daughter and Henry Tudor as part of the coup to overthrow Richard III. However, she went on to allow her daughters to return to Richard’s court and encouraged her son to leave Henry’s camp in Brittany. Her newfound confidence in Richard could indicate that she knew Richard was not responsible for the disappearance of her sons.

The Duke of Buckingham

The Duke of Buckingham, Henry Stafford, is thought to have been involved in the disappearance, though if he was, it remains to be seen on whose behalf he was working.

Buckingham had been well rewarded under Richard’s reign yet in 1483 was involved in a rebellion against him in favour of Henry Tudor. Historians have put forward a number of reasons which suggest Buckingham’s involvement with the princes’ prospective murder and for the failing of relations between him and Richard III:

- Buckingham discovered Richard’s murder of the princes, knowledge which caused him to change sides in favour of Henry Tudor.

- Richard discovered that Buckingham had killed his nephews on behalf of Henry Tudor.

- Buckingham murdered the boys on Richard’s orders but later became disillusioned with Richard’s treatment of him.

- Buckingham himself had a claim to the throne, which itself would have been advanced in the absence of Edward IV’s sons.

Ultimately, we will never know what happened to the princes, short of finding a verifiable historical document that just happened to prove beyond doubt that they were indeed murdered and provide the identity of the murderer, which is unlikely to say the least.

The most likely explanation is that the princes were murdered, though even at the time, there were rumours that the younger prince; Richard, survived and had fled England. This sparked a number of pretenders to come forward, during Henry VII’s reign, claiming to be the survived Richard. The most successful; Perkin Warbeck, not only managed to convince a number of foreign monarchs of his supposed identity, but Henry VII’s agents were unable to disprove his claims. While, again, we cannot know the truth of this one way or the other, were the princes’ remains tested, it would be both fascinating and controversial if only one of the skeletons could be identified as a relative of Richard III.

Want more?

The History of the White Queen: Elizabeth Woodville

The History of the White Queen: Margaret Beaufort

The History of the White Queen: Anne Neville

Follow us for history related nonsense on Twitter @HistoryRemaking

Or on Tumblr