Aaaaaand I’m back, just in time for the lead up to Christmas. The tree is up, the Muppet Christmas Carol has been watched and will be watched at least another fifty times before the twenty fifth, and right now I am attempting to avoid Home Alone. T’is the Christmas season indeed!

Surprisingly though, the birth of Jesus only appears in two of the four gospels. The books of Mark and John omit His birth going straight to the start of Jesus’ ministry, so we must go to Matthew and Luke for our fix of stables, angels, shepherds and travelling kings. As it begins with the birth of Jesus, the book of Matthew opens with Jesus’ genealogy demonstrating his descent from Abraham and King David. There are forty five names here, forty of whom are men. The remaining five (obviously) are women and include Mary, Jesus’ mother. However the choice of the other four women that appear in Matthew’s account are interesting in itself, as it omits the mention of other prominent women from the Old Testament from whom Jesus is descended. Interestingly the four women in question; Tamar, Rahab, Ruth and Bathsheba (“the wife of Uriah”) have very little in common. So much so that scholars are still debating why these women were included while others, many more well known matriarchs were omitted.

There have been suggestions that the four are gentiles and thus illustrate that Jesus’ ministry was not limited to the Jewish people. However one of the more prominent arguments is that the women were at some point, sinners (and of course being women in the Bible this sin is naturally sexual in nature) thus showing God’s forgiveness in action and that no one is outside of salvation. If God can use women who have sinned to bring forth His own son then there’s hope for the rest of us lowly mortals. There is certainly a preoccupation with the early Church and the naming of prominent women in the Bible and early Christianity as prostitutes, adulteresses or seductresses, something which we see in all of these four women.

Tamar

The earliest woman mentioned is Tamar, who appears as the focal character in Genesis 38. Unlike many of the women that we will see, Tamar is not a passive voice in a male dominated narrative, she actually takes matters into her own hands when her father in law fails to deliver on his promises to her.

She is initially found by Judah (one of the twelve sons of Jacob) to be a wife for his eldest son; Er. Before they can settle into marriage and have children, God smites Er for being wicked. We don’t know what he did, but true to the custom of the time Judah then gave Tamar in marriage to Er’s brother Onan (take note Henry VIII). Onan however was not sold on the idea of having children that would be considered those of his deceased brothers and so even though he slept with his wife, he opted to repeatedly pull out so she could not fall pregnant. God saw this and another smiting soon followed leaving Tamar widowed a second time.

With further shades of Catherine of Aragon, Judah decided to betroth Tamar to his next son Shelah but wait until either he was old enough to marry or God smote him too, allowing Tamar to return to her father’s home to wait. Like Catherine, Tamar waited long past the age where Shelah was old enough to marry, but where Catherine simply waited longer, Tamar decided to take matters into her own hands. While the now widowed Judah went out to shear his flock one day, Tamar disguised herself as a prostitute and waited on the road. Judah saw her and invited her to sleep with him, offering her a goat as payment. As he did not have a goat to hand, she accepted his seal, cord and staff as a pledge until the goat arrived and slept with him. After they parted ways she discarded her disguise and returned to her home.

When Judah returned home he sent a messenger out to find the prostitute complete with goat, but the messenger had no luck, as the nearby farmers insisted that there was no prostitute that regularly plied her trade on that road. Some months later it was discovered that Tamar had become pregnant, which caused something of an uproar considering she was an unmarried widow and had therefore, presumably, prostituted herself. When Judah was told he commanded that she be burned for her sin, though before this could happen Tamar sent him a message complete with his staff, cord and seal saying that they belonged to the father of her child. Of course Judah recognised his belongings and had Tamar freed, interestingly claiming that she had shamed him and he described her as ‘more righteous than I,’ because he had reneged on his promise to marry her to Shelah.

However dubious her activities, Judah acknowledged that she was in fact right to seek him out and fall pregnant by him in order to bear children under her first husband’s name. Although confusing, this was the custom of the day, and Tamar was invited to live in Judah’s house where she gave birth to twins (one of whom; Perez, would continue the line to Jesus) though she did not become his wife and they did not resume their relations. She had nevertheless completed her duty to her first husband by bearing children by another in his family, however questionable the actions of disguising herself as a prostitute to sleep with her father in law with the intention of falling pregnant. Although she is acknowledged as having undertaken these actions out of loyalty to her first husband and therefore Judah’s family, the fact that she engaged in prostitution still seems to have stuck to her name which seems to be something of a contradiction. Either she is justified and therefore righteous for following the custom of the day or she is a prostitute, something which cannot be condoned regardless of her motivation and the results.

Rahab

Rahab is one of the more well known women in the list, next to Ruth who has her own book in the Bible. According to the book of Joshua she lived in the city of Jericho as an innkeeper, though in keeping with the Bible’s tradition of naming prominent women as harlots, renting out rooms obviously did not provide enough income and she is also called a prostitute.

The Israelites had recently finished their forty years wandering the desert with Moses and were preparing to enter the land of Canaan. The Israelite leader Joshua dispatched two spies to recon the fortified city of Jericho, while there they hid in Rahab’s inn. When the king learned that there were spies in the city, he sent soldiers to search for them. When they approached Rahab’s inn she had already hidden the spies under flax in her rooftop. She offered to hide them from the king’s soldiers in exchange for the safety of herself and her family when the Israelites came to take the city. With the agreement struck, Rahab misdirected the soldiers and helped the spies escape.

After they had escaped Rahab hung a red cord from her home so that the Jews could recognise the house and spare her family, which they did. When the Israelites had taken the city Rahab stayed with them and went on to marry a descendent of Judah and birth Boaz (who is to become significant in about two minutes). Rahab is interesting because her role has been studied and revised and her story is supposed to illustrate an unyielding faith in God. She was not an Israelite, yet she recognised the power of their God and aided the Israelites in His name. Further emphasis is put on the fact that as a prostitute she was a sinner and yet the depth of her faith overcame her sinful ways. Yet, however much Rahab is looked at, the notion of her as a prostitute is never revised or reconsidered. Even though she evidently owns an inn and is involved in the flax industry nobody seems to have asked the question whether her role as a prostitute is accurate. Instead it is accepted even though she evidently has two other avenues of income.

Ruth

Ruth is probably the woman in this list that we know the most about as she has her own book of the Bible. Ruth is held to be an example of ‘loving-kindness’ and loyalty and is also the problem with trying to group the female ancestors of Jesus as ‘sinners’ as Ruth is popularly considered an exemplary convert.

Ruth lived in Moab where she married into a Hebrew family. Naomi, her husband and two sons had moved to Moab to escape a famine in their homeland and it was one of these sons that Ruth married. After a long but childless marriage Ruth’s husband died, along with his father and brother leaving Naomi, Ruth and another wife Orpah as widows. Naomi decided to return home, releasing Orpah to return to her own family. Ruth however, despite being released from her familial obligations to Naomi, decided to follow her back to Bethlehem. Even when Naomi assures her that she is still young and can remarry where she chooses, Ruth rebukes her assuring her mother in law that she is going to accompany her, become part of her family and adopt the God of Israel as her own.

The two women go to Bethlehem and Ruth converts to Judaism. Because they have no money Ruth takes to picking up crops that farmers have let fall to the ground during the harvest. This is a dangerous job for a woman, but the field’s owner; Boaz, assures Ruth that she will be safe and encourages his workers to let her work unhindered and gives her a gift of grain. Boaz is a relative of Naomi’s deceased husband and Naomi instructs Ruth to dress in her finest and sneak into Boaz’s tent to sleep at his feet in the hopes that he will want to marry her. When she is discovered Ruth reminds Boaz that as a relative of her deceased husband he is entitled to marry her in order to beget children for the family (the same Levite custom we saw earlier in the story of Tamar). There are some small obstacles to their marriage, but these are overcome allowing Ruth and Boaz to marry; their son Obed becoming the grandfather of King David.

The character of Ruth is particularly revered by Jewish converts and she is held to be an example to them. Her loyalty to her mother in law’s family leads her to marry Boaz, even though, upon her widowhood, she became a free woman and able to marry whom she chose. Where then do we get the notion that she was a sinner? It is a bit of a stretch but because she took it upon herself to get Boaz’s attention she dressed herself up and approached him, she can be seen as a seductress. Even though Boaz refers to her as a virtuous woman she is still thought of by some as tainted by the sin of sexual promiscuity through her ‘seductive’ actions. This probably says a lot more about the preoccupations of the early Church than Ruth herself, and also bodes ill for those of us who put on our best clothes for job interviews or meeting important people (harlots that we are).

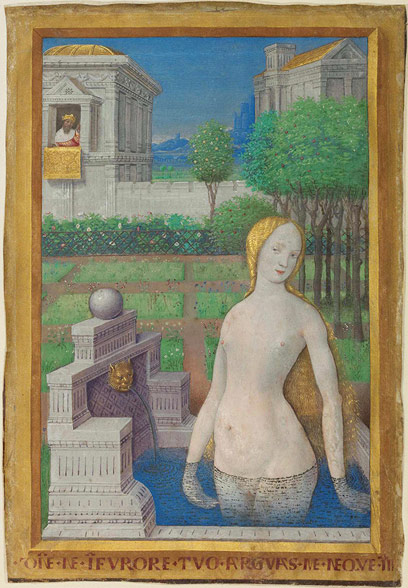

Bathsheba

Bathsheba is probably the most famous of King David’s wives and is also known as, ‘the adulteress’ as she conceived David’s child while married to another man. However, Bathsheba is also a rather passive character in her own story without words of her own for us to consider, and so scholars have been debating how far she is responsible for her own adultery, and there is certainly enough material here to keep feminist interpreters busy until Judgement Day.

The story, without interpretation, as presented in 2 Samuel has David walking along the roof of his house when he glimpses a woman taking a bath. Filled with desire for her he finds his messengers and asks who she is. They tell him she is Bathsheba, the wife of one of David’s soldiers Uriah currently on campaign with the king’s army. David has her brought to him, sleeps with her and she falls pregnant. David immediately resolves to try and hide the fact that she is carrying his child by recalling her husband from the war and keeping him in the palace for a few days, in the hope that during this time he will sleep with his wife and the child can be passed off as legitimate. The oblivious Uriah, however, has no desire to receive favour over the rest of his comrades and so he refuses to go home to his wife, choosing to live as though still on campaign. After David’s repeated efforts to have Uriah sleep with his wife are foiled by Uriah’s integrity, David sends the soldier back to the campaign with a message for the general. Unknown to Uriah the message contains a death sentence; instructing the general to place Uriah on the front lines where he is certain to be killed. As expected, Uriah is killed in battle and Bathsheba widowed. After a period of mourning David marries her, but God was so angered by David’s actions that their first child died shortly after birth. Bathsheba went on to have other children and their son Solomon became king after David and an ancestor of Jesus.

Though Bathsheba is often cast as a willing accomplice to David’s desire, a close reading of the texts must question to what extent this is true. It has been suggested that Bathsheba knew that her house would have been visible from the palace and therefore she deliberately bathed to attract the king, though this in turn begs the question of how she knew the king would be walking along the roof of his palace in order to time her bath so perfectly. This is assuming that it was Bathsheba’s choice in terms of timing, when it is stressed that this was not a standard bath, but specifically to cleanse herself after menstruation. It is also suggested that Bathsheba went with the messengers to see the king of her own volition and therefore bears responsibility for what happened, if she is not reaping the rewards of her plan to ensnare David.

However once again, her compliance is really dependent on a number of factors that require a little bit of imagination. Firstly she would have to be aware that the king intended to sleep with her, which in turn would suggest that she was aware that he was watching her bathing. Secondly it assumes that there would be no other reason for the king to summon her, she may have thought it completely innocent, and considering that her husband was at that time fighting in the king’s army, this is not too much of a stretch to imagine. Finally, even if Bathsheba were aware of David’s intentions how far was she, a woman and currently without her husband to protect her during a time when women’s rights were extremely limited, able to refuse the king, who had complete dominion over her and her family.

There is also the fact that the text states that ‘he slept with her’. Not ‘they slept with each other’, or ‘they lay together’, quite specifically he slept with her, which many an interpreter has taken to mean a lack of consent on Bathsheba’s part. We must also consider that when she hears the news of her husband’s death, Bathsheba mourns deeply which suggests a level of affection for Uriah.

The prophet Nathan, when condemning David on behalf of God, emphasises that the sin is David’s as he sought Bathsheba out, he slept with her and he killed her husband in order to marry her and that God is punishing David, not Bathsheba.

The argument that these women have all committed a sin falls down a little when it is noted that each one is justified in the text that apparently condemns them, if they have sinned at all. Tamar seduces her father in law in accordance to the custom of the time, Rahab may not have actually been a prostitute, Ruth dressed up nicely and lay at a man’s feet again in accordance with Levite custom and Bathsheba may not have been a willing accomplice in her own adultery. Yet as with most women in hagiography and the Bible they are tainted with these sins in order to show the all loving nature of God. The argument that these four women are named because they were not Jews and Jesus’ ministry was not restricted to the Jewish people certainly seems to make more sense as we can see immediately that the four women were not Jews, rather than sifting through their brief stories wondering just where it was that they sinned.