And lo, we come to the third and final sister in our exploration of the extremely unhappy marriages of the Grey ladies. Of the three Grey sisters, Lady Mary Grey was deemed the least likely to assume the role of Tudor heiress. Technically, it was hers to assume; like her sisters, she was the granddaughter of Princess Mary Tudor which gave her a claim by blood to the throne. The fact that she was the youngest of three put her on the outside track of chances that she would ever ascend the throne, as is the case of any younger sibling. But there was something about Mary Grey that seemed to rule her out completely; her height.

All of the Grey girls were slight but Mary was short to the point of deformity, at least by contemporary standards. Their varying remarks record her from “crook-backed” to “the least of all the court” which has led to modern historians attempting to try and make sense of her condition. The results are as varied as the contemporary descriptions. Lady Mary Grey might have suffered from dwarfism, scoliosis, kyphosis, or she may simply have been shorter than average. It’s thought that she was around four feet tall (about 1.2m) which was incidentally about two feet taller than the recorded dwarves of the Tudor court. Whatever her condition, if she even had one, at a time when the outward, physical appearance was seen as a reflection of the soul within, it was vanishingly unlikely that Mary would have been allowed to ascend the throne even if the rare opportunity should arrive.

You might think then, that this would surely have granted her some freedom in her life that her sisters were not allowed. You would be wrong! Although she bore all the hallmarks of a marginalised youngest daughter, Mary was given the same education and opportunities as her sisters. (With the glaring exception of Jane’s brief stint on the throne). She was thus in the unenviable position of being largely ruled out of the line of succession by public perception while being expected to conduct herself as one who might one day be Queen Elizabeth I’s heir. And this absolutely extended towards the subject of her marriage.

Betrothals, Executions, Treasons, and Betrothals

Mary was born in 1545, almost ten years after Lady Jane Grey and five after her middle sister, Katherine. She was eight years old in 1553 when the Lord Protector, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland began making marriage alliances involving the Grey family to bolster his power. Mary was not exempt from his scheming and she was betrothed to her cousin Arthur Grey, heir to the Baroncy of Wilton. He was ten years older than her, already an adult, and accompanying his father on French military campaigns.

Because of the bride’s age, the two weren’t married with the other Grey girls. Not even like her twelve year old sister Katherine who was married with the intent to consummate it later. As a result, there was no need to go through the political rigmarole of dissolving the marriage when Northumberland fell from grace and onto the headsman’s block. Arthur Grey married a woman closer to his own age later that same year and the betrothal was written off as a short lived fancy only briefly committed to paper. It had no further effect on either of them and it’s unlikely they gave it even a passing second thought.

As she was such a small child (in every sense) she shared none of the responsibility for her family’s involvement in Northumberland’s plotting or subsequent schemes. Her father and sister, Jane, were executed the following year while Mary and Katherine remained in the care of their mother who avoided charges of treason.

In 1558 Mary joined the court of her cousin Queen Elizabeth I as a Maid of Honour. Although it had not been formally acknowledged, her sister, Katherine, was considered Elizabeth’s heir presumptive by England’s Protestant elements and so both girls had a comfortable life at court. For two years, they quietly served their mistress and by all accounts, Mary had grown into a young woman of great intelligence even if she had not done much in the way of physically growing. Given how little Mary seemed to be involved in the events that led Katherine Grey to the Tower, we can assume that they weren’t particularly close confidantes. When the news broke in 1561 of Katherine’s secret marriage to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, Mary wasn’t taken for interrogation with the rest of Katherine’s inner circle and was left to watch from the sidelines with the rest of the court.

Mary was sixteen years old when the news of Katherine’s marriage broke and she watched her second sister enter the Tower of London, from which her first had not returned. As a person of royal blood, Katherine had flown in the face in the law when she’d married without permission and her choice of groom had led the insecure Elizabeth to suspect a plot against her. The years passed and Elizabeth’s anger did not lessen. In fact, it only increased when Katherine gave birth to a son and potential heir. It looked as though Katherine would never be released and Mary would have done well to have learned a lesson from her sister. She too was of royal blood, if she married without permission it would not go down well.

But reader, she did not learn this lesson.

We don’t know when Mary met Thomas Keyes though it was probably around 1562. By 1564 the two were clearly smitten with each other and were making plans to marry. There are a number of reasons why we know little about their relationship. For a start, it was conducted with enough secrecy that they avoided the court’s notice but the larger more obvious reason is that nobody was looking at them. Mary was one of the queen’s junior attendants and Thomas Keyes was on the very periphery of court life; they had the luxury of being unimportant enough so as to be ignored.

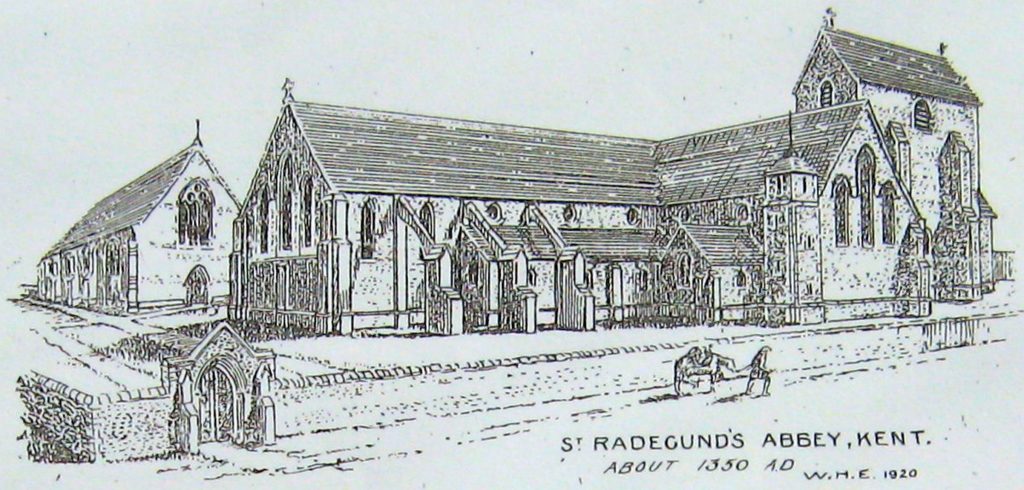

Because Thomas Keyes was such a minor member of the court, little is known of his life. We know that his father, Richard Keyes, was a military officer in the service of Henry VIII. He was involved in the construction of Sandgate Castle in Kent and was granted the lease of St. Radigand’s Abbey after it’s dissolution. After his death, the Abbey passed to Thomas along with a position at Sandgate.

By the time Keyes met Mary, he had been employed in various capacities in service to the crown. He had been an MP for Hythe in Kent, Captain of Sandgate, had assisted in the supression of Wyatt’s rebellion, and had deputised for the Queen’s favourite Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, recording the movement of horses through the Dover port. His career had led him to become the queen’s Sergeant Porter which placed him as head of her security at the palaces. He could often be found at the palace gates and was not easily missed. If Mary was the shortest person at court, Keyes was easily the tallest, dwarfing everyone at a cool six feet nine inches. He was also twice Mary’s age and a widower with children from his first marriage. But none of this apparently mattered to either of them; Mary and Keyes were in love.

Keyes courted her in the traditional sense; sending her small tokens of his esteem and affection. They might have hoped to have asked the queen’s permission and revealed their relationship sooner but there never seemed to be a good moment. Between the constant antics of Mary, Queen of Scots across the Northern border and the problem of Katherine Grey, Elizabeth’s reign seemed to move from one antagonistic succession crisis to another. Such a climate was hardly idea for Mary and Keyes to approach the queen. They couldn’t ask for permission to marry but neither would they put their lives on hold waiting for the opportune moment.

So, they didn’t.

"The Offence is Very Great"

On the 16th July 1565, Queen Elizabeth left court to attend the wedding of her cousin, Henry Knollys. Mary and Keyes had known that only a real emergency would have kept Elizabeth from the event and so planned to be married the same day during her absence.

When the day arrived a minor diplomatic incident almost kept Elizabeth away but it was swiftly rectified and to Mary’s relief, off she went. It was here that Mary revealed the one lesson that she had learned from her sister’s situation. Unlike Katherine, she was going to ensure that there were plenty of witnesses. If the queen reacted badly, there would at least be numerous people to swear that the marriage had taken place. There would be no legal wrangling as to the legitimacy of the union; Mary was going to be Mrs Keyes and wasn’t going to give the title up once she was.

That evening, in the presence of friends and family on both sides, Mary and Keyes were married. After a brief ceremony, the guests retired for a celebratory meal and the couple went to bed. They were well and truly married and nobody could doubt the legality of it. Historian, Leanda de Lisle, suggests that Mary might have banked on her choice of groom saving her from imprisonment. Unlike Katherine, she had married a man so lowborn that their children couldn’t possibly have threatened Elizabeth. Her mother had done the same and although she had been banished from court, she had been allowed to live with her husband and they had gone on to have three children together. Mary might have hoped for the same kind of response.

Mary was very very wrong.

Her idea to have more witnesses meant that there were more people to gossip and within a few months, rumours of the secret wedding were starting to circulate. On the 21st August, Elizabeth discovered the marriage while still reeling from the news that Mary, Queen of Scots had made her own marriage. The Queen of Scot’s marriage to Lord Darnley threatened Elizabeth’s throne far more than that of the lowly Mary Grey and the sergeant porter but Elizabeth was no less furious. She might have been more so given that she could actually do something about Mary Grey.

The couple were separated and imprisoned but they probably thought they might be able to recover the queen’s favour or at least one day be allowed to live together once her anger had dissipated. It’s unlikely that either of them would have entertained the idea that they would never see each other again.

Imprisonment

Unlike Katherine Grey and her groom, Mary and Keyes were not imprisoned together. In fact, because he hadn’t an ounce of noble blood, Keyes was imprisoned as a commoner at Fleet Prison. He was placed in solitary confinement in a cell far too small for man his size where he was denied even basic exercise. Mary was given a little more consideration. Though she too was put into solitary confinement she had a friendly jailor in Sir William Hawtrey who had recently refurbished his house at Chequers.

For two years, Mary wrote to Cecil, pleading for his intercession with the queen but to no avail. Elizabeth would not be moved. Mary was allowed out of her rooms for the bare minimum of exercise and served by a single lady and one groom. While undoubtedly several steps down from what she was used to, she was in an immensely better situation than her husband. His conditions were so bad that his health inevitably suffered and he wrote to Cecil even more than his wife. Keyes begged Cecil to intercede with the queen and have him released and offered all manner of things in compensation. He offered to live in exile for the rest of his life, he volunteered for military service in Ireland, and above all he offered to annul the marriage.

Unfortunately, their insistence on having a legal wedding that nobody could doubt the validity of now ensured that now came back quite roundly to bite them on the ass. They had done everything they could to ensure the queen could not annul their marriage and even with Keyes offering it, the Bishop of London found no legal reason upon which to dissolve it. In investigating the case, however, the same bishop managed to gain Keyes the one single, brief reprieve he would be granted. Upon his insistence, the queen allowed to Keyes to take some exercise in the adjoining prison gardens but this was short lived. Within a matter of months, a new warden took over at Fleet and Keyes was once again locked away, this time without any priveleges.

In the August of 1567, Hawtrey was tasked with escorting Mary to a new place. She was to suffer house arrest but this time in the household of her step-grandmother, Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk. Ahead of her arrival, Hawtrey warned the Duchess that Mary had little in the way of personel effects and that her furniture was in such poor condition that at Chequers he had furnished her rooms himself. The Duchess thought that he had exaggerated until she saw the state of her granddaughter and her luggage which prompted a hasty letter to Cecil asking for the queen’s assistance.

The situation was exarcebated by the death of Katherine Grey early in 1568, leaving Mary the sole Grey heiress. Elizabeth was not inclined to treat Mary Grey kindly but some mercy was finally shown to Keyes. After suffering under the cruelty of the warden, he was finally released. He hadn’t recovered the queen’s trust, he wasn’t allowed to see his wife, but he was at least out of the Fleet and away from a man who had once fed him meat in a sauce of dog medicine.

For Keyes, things were looking up. In 1569 he was still in disfavour but was allowed to return to his home at Sandgate Castle which he was once again appointed captain of. Mary, on the other hand, was moved into the custody of Sir Thomas Gresham, a prominent London merchant who could afford to furnish and keep Mary in a decent manner without having to bother the queen about it. She was right in that Gresham didn’t bother the court for money but he wrote repeatedly and frequently begging first Cecil, then Dudley, then anyone who would listen to have Mary removed from his care.

For as long as Mary was in their custody, Gresham and his wife, Anne, found their lives severely curtailed, unable to leave Mary alone even while she was locked away in their lesser used rooms. Matters weren’t helped by the crippling pain Gresham experienced from a severe riding injury that never quite healed or the fact that they had not long lost their only son and heir. Mary didn’t want to be there and the Gresham’s didn’t want her there. Elizabeth didn’t care and Mary remained at her unhappiest prison for almost three years.

Mary Grey, Widow

Having been released, re-appointed to Sandgate Castle, and presumably reunited with his children, Thomas Keyes turned his attention to trying to bring his wife home. He was not successful. The queen ignored all his requests but she wasn’t bothered with them for long. In 1571, three years after he’d been released from the Fleet, Keyes passed away. It’s thought that he never quite recovered his health after his stint in prison.

Mary was informed and took the news badly, as one would expect. Even Grensham felt enough at her grief to write to Cecil. But there was an underlying hope that now that Keyes was gone, there was no reason to keep Mary imprisoned. She had married without permission but following the death of her husband, there was no marriage to threaten the throne and she was unlikely to do it again. Gresham would surely be free of her company soon.

But while Gresham might have hoped that Mary would be released at the very least out of his custody, Mary was writing to the queen asking that she might be allowed to raise Keyes’ orphaned children and styled herself his widow. The result that she was moved from Gresham’s house at Bishopsgate to the house he had recently begun constructing at Osterley. And the Greshams had to move with her. If it was at all possible, this only made them hate her more.

Anne Gresham was now beyond desperate to rid herself of Mary, as reflected in her husband’s increasingly frantic letters to Cecil. Meanwhile, Mary had asked to be released into the custody of her widowed stepfather, Adrian Stokes. The queen clearly thought it was a good idea, or was at least persuaded into it by Cecil. The following year, Stokes remarried, and shortly afterwards Mary was permitted to go home.

The Greshams’ attitude towards Mary did not soften now that they had gotten their way. They were glad to see her off, rejoicing that she was gone “with all her books and rubbish.” She was welcomed into her stepfather’s new family in the home she had lived with her mother and Katherine and relished in their company. From here, Mary wrote to Katherine’s husband and sought news of her nephews, as well as her orphaned Keyes stepchildren. She had been separated from the world and her family for seven years and seemed to be determined to embrace those bonds.

Despite this, she also wanted to live a life, and so after just a few months with the Stokes, she moved into a property of her own in London. She maintained friendships with women she had known at court, pursued her interest in religion, was careful to avoid anything controversial that might lead her into disgrace again, and in the meantime she prioritised two things; restoring the queen’s favour and caring for her stepchildren.

We don’t know how many children Thomas Keyes had with his first wife. The historical record only knows of two but both his and Mary’s letter hint at more. In her widowhood, in the comfort of her own home, Mary became close to her stepdaughter Jane Merrick. They grew close enough that Jane named her daughter for Mary and Mary was invited to be her godmother. It was to little Mary Merrick that Mary left her house and estate in her will.

By the end of 1577, Mary was finally returned to Elizabeth’s good graces. She was appointed Maid of Honour once more but forbidden to use the name Mary Keyes. She was once more Lady Mary Grey, the Queen’s cousin. She returned to court for Christmas and spent a happy holiday season at the queen’s side exchanging gifts and enjoying the many entertainments. But Mary’s return was incredibly short lived. In the new year, the plague hit London and the court fled as they were wont to do. Mary however returned to her London home. Whether it was the plague or some other illness, Mary fell ill and on the 20th April, her thirty third birthday, she died.

Unlike her sisters, Mary died in the queen’s favour, something which was reflected in her funeral arrangements. She was buried in Westminster Abbey in her mother’s tomb with the full honours expected of the queen’s cousin. There were heralds, mourners, and pall bearers. Elizabeth didn’t attend as was tradition, but plenty of Mary’s friends from court did, and some of them had been witnesses at her wedding.

Mary married for love but her marriage was no less unhappy for it. Not because of her choice in groom but because of the separation they endured. Like her sister, she was clearly deeply in love with her husband and would spend her life trying to achieve that recognition. Even when the queen demanded she use the name Grey and set aside her married name, she agreed while styling herself Keyes’ widow on the side. Her relationship with Jane Merrick shows how dedicated she was to her husband’s memory, as does the portrait she had painted the year that her husband died which highlights her wedding ring. Mary Grey might have been buried under her maiden name but she never stopped being Mrs Keyes.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.