Recently, I wrote about Lady Jane Grey and her extremely unhappy marriage to a man she despised. By contrast, her sister Katherine would have two marriages to men she loved deeply, and who loved her back, but by dint of her place in the succession, and Elizabeth I’s seeming determination to snuff out love among her ladies wherever she found it, neither of these marriages brought her much happiness.

Marriage #1: Henry Herbert

Like her sister, Jane, Katherine Grey’s marriage was engineered by the Lord Protector, John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. While his plot was centred around Jane Grey and her marriage to his son, he shored up alliances through a series of marriages between his allies and prominent nobles. Among them was William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke. Dudley had ousted Pembroke from court during his ascendence and Pembroke was continuously looking for an opportunity to return to power. When Dudley began arranging marriages, Pembroke offered his son, Henry Herbert into the mix. As well as heir to the Earldom of Pembroke, Henry’s mother was a sister of Catherine Parr tying him to the royal family through Henry VIII’s sixth marriage.

Twelve-year-old Katherine and fifteen-year-old Henry were married in a triple wedding alongside Katherine’s sister Jane in May 1553. The ceremony was lavish though young Henry was still mourning the loss of his mother a year earlier and was apparently in poor health. After the wedding, Katherine and Henry went to Baynard’s Castle, Pembroke’s London residence, where they would live under the same roof but in separate quarters. Given the bride’s age and Henry’s health, there was no rush to consummate the marriage.

Katherine was still at Baynard’s Castle two months later when her sister became queen. Pembroke remained Dudley’s ally only for the first few days of the coup. Once Dudley was no longer physically present to enforce his will, Pembroke and the Privy Council gathered at Baynard’s Castle and declared for Mary Tudor. With Dudley’s plan in ruins and those who had supported it almost certainly facing charges of treason against the newly declared Queen Mary, Katherine’s parents went to Baynard’s to meet with Pembroke. Their hope was to convince him, as they had convinced others, to turn Dudley into the scapegoat for the entire situation, saving themselves and their family.

While Pembroke might have agreed to turn on Dudley, he no longer wanted to be connected to them and his son’s marriage to Katherine was an inconvenient tether. An annulment would have been relatively simple to acquire and so he informed his son and daughter-in-law of his plan. He did not anticipate their reaction. Despite their age and the fact that they had been married for only two months, Henry and Katherine were deeply attached to each other. Neither agreed to the annulment, protesting that they had consummated the marriage and were fully husband and wife.

It’s unlikely that this had actually happened, as Pembroke well knew, but he delayed the annulment process until it was confirmed that Katherine was not pregnant which could be the only proof of consummation. In the meantime, Katherine was sent back to her mother to ensure that the couple couldn’t fulfil their protests. Despite their devotion, Katherine and Henry’s marriage was annulled the following year with Queen Mary’s permission. The same year saw Katherine’s sister and father go to the block for treason, while Pembroke rose in court for his role in suppressing a rebellion which sought to overthrow Mary in favour of Jane (again).

The Queen’s Cousin

Despite their precarious position, the reduced Grey family did not fall into despair. Katherine’s mother, Frances, was the queen’s first cousin and quickly reconciled with her. Within six months of the executions, Frances was back at court with both her daughters in attendance. Katherine was now third in line for the throne behind Elizabeth Tudor and Mary, Queen of Scots. Katherine was however the English favourite when compared with the Catholic and French Mary which raised her profile somewhat.

On the night before her execution, Jane had written a letter to Katherine. It was everything one would expect from Lady Jane Grey in that it was a long treatise on how her sister should prepare her soul for martyrdom. Katherine might be about to escape any connection with the plot to put Jane on the throne, but she was still a Protestant. Jane knew that the Catholic Queen Mary wouldn’t suffer Protestants at court and so she expected to see her sister in heaven soon. Despite Jane’s assurances that God would not take into account Katherine’s youth when condemning her if she were to follow Mary’s Catholic policy, Katherine did just that. While she never engaged in a public renunciation of Protestantism, she and her mother both went to the Catholic mass and acted the part under Mary’s reign. We don’t know her feelings on the matter but Katherine clearly didn’t have the same unrelenting devotion to the Protestant cause as her sister. She seems to be happy to keep her head down, appear Catholic, and tacitly support Elizabeth’s succession without ever drawing attention to it. She was a popular girl at court, in attendance on the queen, with her own rooms and attendants. The only thing Katherine seemed to have any strong opinions on was her marriage to Henry Herbert. Their marriage had been annulled but both spoke of the other often and thought that if they could get the queen to agree then they would remarry.

A year after arriving at court, Katherine’s mother was sent away. She had married again and while her choice of husband, namely her Master of Horse, Adrian Stokes, was lowborn enough to ensure the match didn’t threaten the succession, she hadn’t sought the queen’s permission and so lost her position. Her daughter Katherine was put into the care of Anne Seymour, Duchess of Somerset. Her husband, now deceased, had been the brother of Queen Jane Seymour and Edward VI’s uncle. He had been the first Lord Protector of the young king’s reign until Dudley had ousted him. Anne Seymour had gone to the Tower with her husband and remained imprisoned there after his execution. She was released when Mary became queen and quickly recovered her position.

For Katherine, little changed. She remained at court and already knew the Duchess of Somerset well. She was, in fact, the best friend of the Duchess’ daughter, Lady Jane Seymour. Both girls had grown up together, were close in age, and had the unenviable shared experience of losing their fathers to the executioner’s block. They were known for being extremely close and in the summer of 1558 when influenza swept through the court, Katherine and Jane went to one of the Somerset’s London houses; Hanworth Palace. Jane’s brother, Edward Seymour, the Earl of Hertford, was also present and romance quickly blossomed between him and Katherine.

We don’t know when exactly it was that Katherine turned her attention from Henry Herbert or why. By the time Katherine and Edward Seymour (whom she affectionately called Ned) began their summer affair, Henry was abroad fighting alongside the queen’s husband. They might have already given up hope that the queen would allow them to remarry or maybe they simply lost interest. Whatever the reason, Katherine and Hertford quickly fell in love.

Before the summer was over, it’s likely Hertford proposed marriage. The Duchess of Somerset quickly intervened. She demanded that Hertford break off any kind of relationship with Katherine but to her surprise, he refused. With the worst of the epidemic over, The Duchess was saved when Katherine and Jane returned to court before Katherine had given her answer.

The Queen’s Heir(ish)

Events at court quickly left Katherine no time to consider her relationship with Hertford. Queen Mary had been ill since May and her health continued to decline. Within eight weeks of Katherine and Jane’s return to court, the queen was dead and Katherine had a leading role in her funeral. She shifted from a prominent position at court under Mary, to a prominent position at court under the new Queen Elizabeth. She was now tacitly second in line to the throne, behind only Mary, Queen of Scots.

In the early months of Elizabeth’s reign, Hertford seems to have pulled back from Katherine, probably at his mother’s behest. In the meantime, the Spanish ambassador recognised Katherine’s political usefulness and approached her about possible marriages to a Hapsberg noble. Katherine agreed though she was unaware of how far Spain was prepared to go and, at one point, there was a plot to kidnap her. Ultimately, the negotiations she was aware of and those she was not, fell through when the King of France died, changing the political face of Continental Europe.

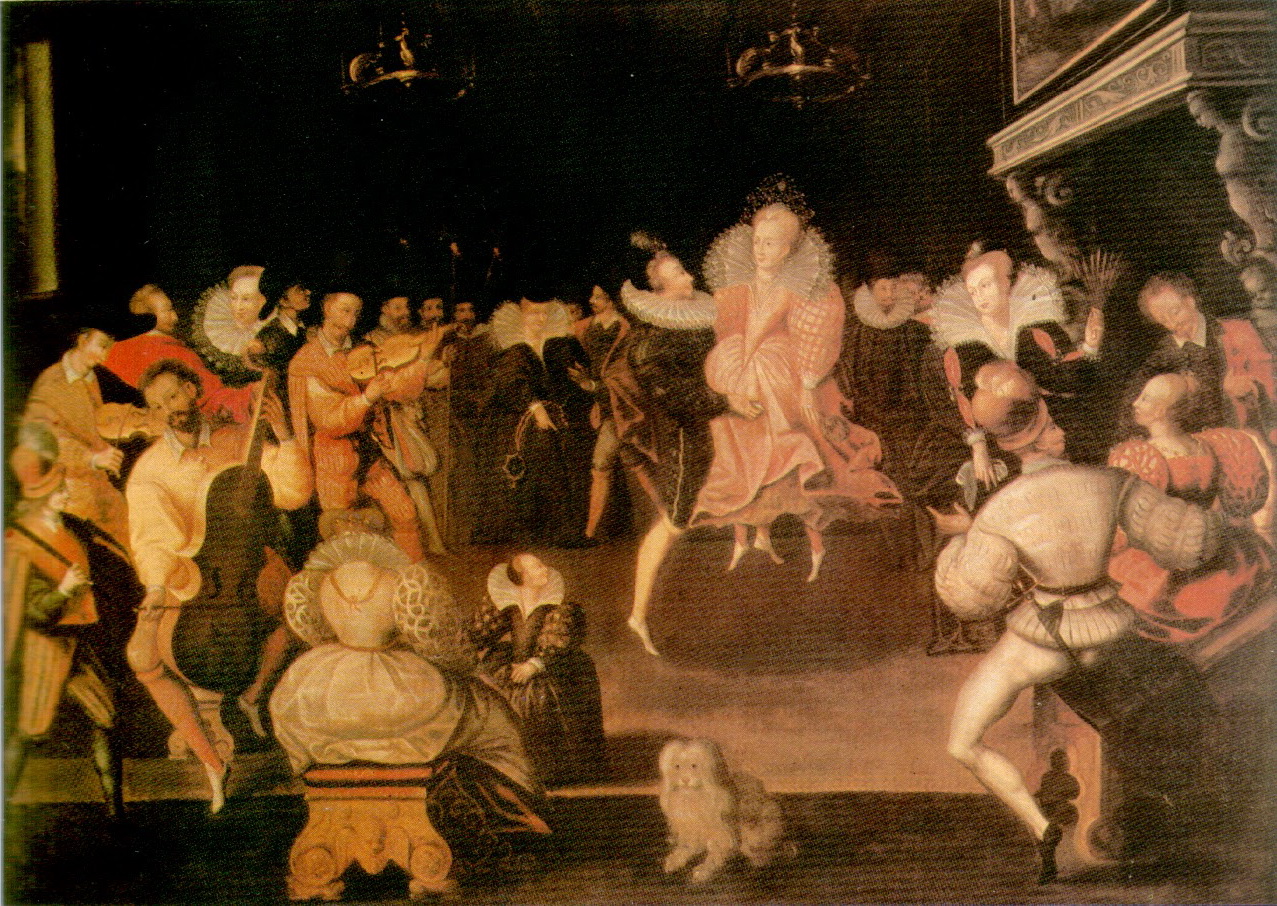

The following summer, Elizabeth went on the first progress of her reign. Katherine, naturally, went with her and was reunited with Hertford despite the Duchess of Somerset’s interference. Their initial romance quickly became something more and it was widely remarked that they were in love. Elizabeth was oblivious to this development being thoroughly engrossed with her own romance with the married Robert Dudley.

After the progress ended and with the court returned to London, Hertford rode to Frances Grey’s house at Sheen and asked for permission to marry Katherine. Frances agreed but with conditions. Firstly, she would speak to Katherine and determine that it was what she wanted. Secondly, Hertford would secure political support for the match because she thought it unlikely Elizabeth would agree.

While Katherine visited her mother and assured her that she wanted nothing more than to marry Hertford, Hertford returned to court and began approaching his allies within the Privy Council. The response was lukewarm. The match was an excellent one on paper; Katherine was high in the ranks of succession and Hertford was distantly descended from Edward III. Hertford was the nephew of Queen Jane Seymour and his father had been the first Lord Protector to Edward VI. Any child of theirs would be of royal blood and more importantly, far more Protestant than Mary, Queen of Scots. Any child of theirs would also potentially threaten the illegitimate Elizabeth.

At the time, Elizabeth was being formally courted by Erik of Sweden. In the hopes of securing her potential husband’s support, Hertford befriended Erik’s proxy and brother. Erik’s suit, like those of all Elizabeth’s suitors, came to nothing but neither Hertford nor Katherine gave up on each other. Hertford wrote her frequent poems and they knew that if they were patient enough to garner support, they would be allowed to marry.

Shortly after Hertford’s proposal, Frances died, pressing pause on any thoughts of marriage. While Katherine mourned her mother, there was talk of Elizabeth adopting Katherine which made her marriage the purview of the Privy Council. This allowed Hertford’s supporters on the council to legitimately recommend him as Katherine’s husband.

In the meantime, Elizabeth had continued her public flirtation with Robert Dudley. Their behaviour was a scandal across Europe and it put her throne in jeopardy. With Elizabeth on the brink of ruin, her greatest advisor, William Cecil, approached Hertford and offered his support for a marriage between him and Katherine. A Protestant Katherine was preferable to the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots for the Privy Council and with Elizabeth’s reign reaching breaking point, sides had to be chosen.

Once again, events conspired against the happy couple. Robert Dudley’s wife died in suspicious circumstances. An inquiry was launched into her death and while it cleared him of any wrongdoing, he would be forever tainted by the scandal. Having already risked her throne without marrying him, Elizabeth accepted that marriage to Robert would open her up to accusations of complicity, if not the murder itself. With her reign stable again, Cecil once more approached Hertford. This time he warned him off Katherine altogether as the queen would never approve and they would never again gather as much support as they had just lost.

Unaware that Cecil had withdrawn his support, Katherine was faced with sudden silence from Hertford. With rumours that he had transferred his affections to another woman, she wrote him a furious letter forcing him to respond. Hertford wrote back assuring her of his love and once again asking her to marry him, this time without the queen’s permission.

Hertford then attended court under the guise of visiting his sister. With Jane as a witness, in her chambers, Hertford and Katherine were formally betrothed. They promised to marry as soon as the opportunity presented itself; namely, when the queen next left court. In a ceremony as binding as a wedding, Hertford gave Katherine a diamond ring, kissed the almost bride, and the two were practically married.

Marriage #2: Edward Seymour

In December 1560, a little over a year after Hertford had visited Frances Grey to ask for Katherine’s hand, the two were finally married. The queen had decided to take a brief hunting trip to Whitehall and the two seized upon the opportunity of her absence. Katherine feigned illness and asked that Jane be allowed to remain with her while she recovered. The queen agreed and plans for the wedding were put into place. They agreed to meet at Hertford’s house at Cannon Row as soon as the queen had departed where they would be married with Jane as a witness.

On the day in question, Hertford quickly had the house cleared of servants by giving them all an impromptu day off but some of them were still present when Jane and Katherine arrived shortly afterwards. There was a brief round of greetings before Jane almost immediately left to retrieve a priest Hertford already had on standby. They returned swiftly and the wedding was underway.

As part of the ceremony, Hertford gave Katherine a ring of five gold links inscribed with the lines of a poem he had written for her. The priest married them, received a generous purse from the groom’s sister, and then Jane left the couple to consummate the marriage. The two remained in bed until it was time for Katherine and Jane to return to court. By now the servants had returned and were well aware of what was occurring within their master’s bedroom even if they didn’t understand the extent of it.

Now that they were married, Katherine and Hertford had to keep the secret. They didn’t spend the night together but this was all they allowed for. They met frequently and each time would retire together, something which was difficult to keep from the wider court. Soon, Katherine was fending off questions from relatives and friends about her familiarity with Hertford, while Hertford himself had come to the attention of Cecil.

Afraid that Hertford and Katherine’s feelings might overwhelm them, Cecil arranged for the couple to be separated. Hertford was to go on a tour of the European courts where he would hopefully learn a great many things that would prove useful in his service to Elizabeth. However, before the appropriate papers could be prepared, disaster struck with the death of Jane Seymour.

Katherine and Hertford were devastated by her loss and not just because she was the only witness to their wedding. They had long since lost track of the priest that married them and without Jane, there was nobody beyond Katherine and Hertford to say the event had ever happened. But Jane had also been close to both of them. She was Katherine’s best friend and a beloved sister. Their feelings were complicated by Hertford’s imminent departure for the Continent and something else; Katherine suspected that she might be pregnant.

On the day that Hertford left, he met with Katherine but she still couldn’t confirm that she was pregnant. He left her with some money and a promise that he would return immediately if she found that she was with child. He also gave her a will that affirmed their marriage and her right to his property in the event of his death. They shared a kiss and then Hertford was gone. Katherine went inside where she was met by Cecil. He wanted to reassure her that Hertford’s absence was necessary and remind her that she shouldn’t attach herself to him.

The warning came too late. Katherine was indeed pregnant.

Discovery

Katherine was entirely alone at court. With Jane dead she had nobody to confide in and with her husband abroad she had no protection. She wrote several letters to Hertford but they went without a reply. The passing weeks became months and Katherine still hadn’t heard from him. Her pregnancy was advancing and she needed a solution.

At this point, Katherine’s former father-in-law, the Earl of Pembroke offered his son in marriage to her… again. With talk of Katherine becoming Elizabeth’s formal heir, as well as her de facto position in the succession, she was once again an excellent choice for his son’s bride. On top of that, he could easily capitalise on their prior relationship and the fact they had spent so many years trying to get themselves into this very position. With no word from Hertford and so few options, Katherine readily accepted.

Henry was delighted. He immediately showered her with gifts, sending her tokens of his devotion, and letters reassuring her of his affection. Katherine was reserved in the responses, still holding out hope that Hertford would return suddenly and she would be saved. To this end, she wrote him yet another letter telling him that she was carrying his child. While this letter did indeed make it to Hertford in France, its contents were also made known to Henry Herbert.

Henry was not impressed, to say the least. In his next letter, his affection was replaced by condemnation as he denounced Katherine as a whore. Not only did he know about her pregnancy but he knew that she was prepared to marry him in order to cover the fact. He demanded the return of the gifts he had given to her. On paper this was so Henry wouldn’t be connected with Katherine or Hertford when the scandal was revealed but it wouldn’t be a stretch to think part of it might have been related to the legitimate hurt he felt at her betrayal. When Katherine failed to respond in any way, he followed up with another letter, this one threatening to reveal her situation to the court.

Ultimately, he kept her secret but it was a short-term solution. Katherine was now heavily pregnant and struggling to hide it. She had only a couple of months left before the baby was born and the queen discovered the clandestine marriage. With no one else to turn to, Katherine revealed her situation to one of her friends at court who was known for keeping a level head. In the face of such a revelation, her friend did not keep a level head. In fact, she berated Katherine extensively for not speaking with the queen beforehand and the following morning, Katherine was excruciatingly aware of the gossip that followed her. She now had no option but to tell the queen before she inevitably discovered it from someone else.

With no other options before her, Katherine approached Robert Dudley. He was the only person who could deliver news of any calibre to the queen without a loss of her favour and he was, through the marriage of their siblings, still Katherine’s family. They weren’t close friends but she needed someone to protect her from Elizabeth’s wrath.

She approached Dudley in his rooms after the court had retired for the evening and revealed her situation. Dudley was horrified and not just because she was so heavily pregnant. She was standing in his private chambers which adjoined those of the queen. If Elizabeth overheard them or if they were caught then her favour would most certainly be lost. He needed to get her out of his rooms and to that end, he promised her everything. Intercede with Elizabeth? Sure. Put in a good word for her and Hertford? Absolutely. Whatever she needed.

At the very earliest opportunity, Dudley went straight to Elizabeth and told her everything. Katherine and Hertford’s marriage was revealed along with the advanced pregnancy.

Elizabeth was livid. Her cousin of royal blood had married without permission and was carrying a child. In doing so, she had disrupted the succession as well as plans Elizabeth had been entertaining for a Scottish marriage. But worst of all for Katherine, Elizabeth didn’t believe that this was a love match gone too far. She thought that this might be part of a larger plot against her.

The Queen’s Wrath

On the day that Elizabeth discovered the marriage, anyone suspected to have been involved with or have knowledge of the event was taken to the Tower of London to be questioned. The exception was Robert Dudley who had convinced the queen that he had known nothing until Katherine had revealed it to him the night before. Katherine had judged that correctly at least. She herself was imprisoned in the Tower of London and questioned extensively but she refused to say anything, not even to speak in her defence.

Across the Channel, Hertford had received all of Katherine’s letters but for some reason had let them all go unanswered. Contrary to how this appears, he doesn’t seem to have abandoned Katherine. Instead, it seems that his character was to avoid situations until they became unavoidable as we see in his reaction to the queen’s discovery.

Aware that his wife had been arrested and imprisoned, that the queen was livid, and that he had been recalled to England, Hertford treated the queen with the same respect he had treated his wife; he ignored all her letters and hoped that the situation might resolve itself.

It was not the most successful of strategies. The queen dispatched Sir Nicholas Throckmorton to drag Hertford back to England. Hertford managed to delay the return by a few more days but even after Throckmorton put in a good word for him with the queen, Hertford was taken straight from port to the Tower of London. He was not allowed to see his wife who was kept in separate rooms but Sir Edward Warner, Lieutenant of the Tower, allowed him to send her some tokens, flowers, and messages, reassuring her of his devotion.

The questioning continued but with the only witness to the marriage dead and no way to track the priest, little information was forthcoming. It was clear that nobody knew anything and Hertford’s mother was swift to disavow any knowledge of the event. Warner continued to question Katherine but in the summer of 1561, he wrote to Elizabeth stating that in the time she had been there, she had never suggested that anybody else at court had knowledge of her wedding. Eventually, it was accepted that there had never been a court conspiracy to dethrone Elizabeth in favour of Katherine. Despite this, the couple remained in prison.

On the 21st September 1561, Katherine gave birth to a baby boy who was named for his father; Edward Seymour, Lord Beauchamp. The birth of a son and heir complicated their position but Katherine and Hertford were overjoyed. Although they were prisoners, they were quite comfortable, and through the sympathy of Sir Edward Warner, the couple were allowed to visit each other frequently. When Warner wasn’t available, Hertford bribed the guards. The inevitable happened; in 1562 Katherine fell pregnant again.

The End of Life…

The birth of little Edward Seymour had strengthened Katherine’s claim to the throne and a severe illness that almost ended Elizabeth’s life, as well as her reign, forced the issue of succession. While there were a handful of lesser candidates, the most obvious contenders with the largest support were still the queen’s cousins; Katherine and Mary, Queen of Scots.

Elizabeth survived her illness but found herself under renewed pressure to name her successor and marry so that she could secure the throne herself. Elizabeth had no intention of doing either and it was while she was defending herself in this regard to parliament that news of Katherine’s pregnancy reached them. The timing could not have been worse for the couple who once again found themselves on the receiving end of Elizabeth’s wrath.

The investigation into Hertford and Katherine’s wedding was renewed. The only witness was still dead, and the priest still could not be found, but this time the couple had new support from the public. While there was still no proof of their marriage, they had both sworn, to the Archbishop of Canterbury no less, that it had happened. For many, this was enough to legitimise their marriage as was the fact that they had been allowed to visit each other and conceive a child in prison. For his role in the affair, Warner was remanded to his own prison.

Around February 1562, Katherine had her second child. To further insult an already furious queen, this one was also a boy. His parents named him Thomas and like his brother, he was baptised at the chapel within the Tower’s grounds where his aunt’s beheaded body had been laid to rest. On the same day, Hertford was taken before the Star Court to finally answer the charges against him. He was found guilty of seducing a virgin of the queen’s blood, impregnating her (twice), and breaking the conditions of his imprisonment. He left the court with a crippling fine but with his marriage still intact. He was not, however, allowed to visit his wife upon his return to his rooms.

In the summer of the following year, the family was broken up as the plague struck London. Elizabeth and the court retreated from the city and Katherine successfully begged the queen to allow the same for herself and her family. Elizabeth agreed but strict conditions were imposed. Hertford and little Edward were sent to the Duchess of Somerset’s home while Katherine and Thomas went to Katherine’s uncle, Lord John Grey.

The separation was particularly hard on Katherine though she was buoyed by her uncle and Cecil’s support for a petition to the queen that would hopefully result in forgiveness for the young family and a return to courtly life. Despite the rules prohibiting the couple from communicating, they exchanged a handful of letters, including a scandalous one from Katherine that detailed her hopes for the queen’s imminent pardon so that they could get back to sharing a bed.

Elizabeth, however, could not be moved. She firmly rejected the petition in a blow from which Katherine never recovered. To make matters worse, in the coming years, the family were moved and further separated. Hertford was sent from his son while Katherine and Thomas were placed in a series of new houses to act as their prisons. In 1567, she was moved to Cockfield Hall in Suffolk, her fifth prison in seven years.

In the years since her failed petition, Katherine had suffered greatly for the separation from her husband and eldest son. Everyone given charge of her was given increasingly harsh instructions as to her treatment but Katherine was unfailingly pleasant and everyone she stayed with remarked on the gentleness of her disposition. Elizabeth, by contrast, was seen as unnecessarily cruel to treat her cousin the way she did which only increased the queen’s hostility.

By the time Katherine reached Cockfield Hall, she was convinced that she would never be reunited with her family and began to waste away. She was only twenty-seven but could not be roused by anyone. She was completely prepared to die and to that end, it’s thought, she slowly starved herself.

In her final hours, she begged that the queen treat her sons with mercy and finally turned her attention to bequests for her husband. She entrusted to her latest jailor her wedding ring, the diamond ring Hertford had given to her upon their betrothal, and finally a third ring to remember her by engraved with her final message to him; ‘While I lived, yours.‘ She died shortly afterwards, only fourteen days after arriving at her new prison.

…But Not of Love

In a time where marriages among the nobility were largely arranged by others, Katherine was unusual to have found love with both her husbands but there is no doubt that Ned Seymour was the great love of her life. Unfortunately, whatever happiness she found with him was short-lived. Her position as Elizabeth’s de facto heir caused the queen to repeatedly punish her for the marriage, often for reasons that had nothing to do with Katherine herself. Katherine was mostly ignorant anytime somebody pushed for her formal recognition as heir but she never failed to face the repercussions from the slighted queen.

When Katherine died, Hertford was finally released from his prison and allowed back at court but his marriage went unrecognised and his sons considered bastards. Their eldest son, Edward, followed in his parents’ footsteps by falling in love with a woman he was utterly forbidden to marry. Honora Rogers was the lowborn daughter of a knight and hardly the stock the Earl of Hertford wanted for his potentially royal son. Edward would not be dissuaded, dramatically promising to kill himself when his father tried to separate them.

Ultimately, he was allowed to marry her when Queen Elizabeth intervened on their behalf. Having now thoroughly cultivated a reputation for jealousy this was a surprising move, until the court realised that such an unsatisfactory marriage damaged his claim to the throne irreparably.

Meanwhile, his brother Thomas campaigned to have their parents’ marriage legally recognised but he did not succeed in Elizabeth’s lifetime. Her animosity towards the couple didn’t soften even so long after Katherine’s death. On her deathbed she disinherited the Greys despite Cecil’s support of them in life.

In 1608, almost fifty years after his wedding to Katherine, and five years after the death of Elizabeth, Hertford finally sought the priest who had married them. The new King James recognised the validity of the marriage, allowing Hertford’s heirs to inherit the Earldom of Hertford and the related titles. Hertford himself lived to the extraordinary age of eighty-two. When he died in 1621, his grandson and heir, William Seymour, the new Earl of Hertford immediately had Katherine Grey taken from her grave in Suffolk, where she had died, and brought to her husband.

The two were laid to rest in Salisbury Cathedral where their tomb was engraved with an inscription detailing how, although separated in life, they were reunited in death, but had never been anything but in love.

Coming soon: the unhappy marriage of the final Grey sister; Mary. Until then you can join me for behind the scenes research and all manner of other historical tidbits at my Patreon.