During the medieval/early modern period (and many others but I’m working to a deadline here), a woman was defined by her marital status. As an adolescent, she was unmarried and therefore a virgin. As an adult, she’d marry and would either die a wife or survive a widow. The sex lives, imagined or real, of courtiers and royals, are a common subject for modern historical fiction and will inevitably touch upon the person’s marriage. Few people remained single at this time and those who did usually took vows of celibacy and retired to a religious institution. Fictional marriages however are rarely representative of the state of marriage at the time and as a disclaimer let me just say that this will focus on the marriages of royals and courtiers as shown in fiction, and isn’t a study of the institution during the Tudor years.

Typically, a fictional Tudor marriage is shown to be oppressive and restrictive for the woman and if we take a legalistic view of it we can certainly see how this is the case. On paper, Tudor men had complete power over their wives. Upon marriage, a woman’s dower lands became the property of her husband for him to administer as he saw fit. If she outlived him she would regain those lands (or the equivalent if her husband had traded, sold or lost them) and hope that he had looked after them in the meantime. She lived where her husband chose for her to live and if her behaviour offended him, he could have her sent away to a house of his choosing, regardless of how fit it was for purpose (see also: Katherine of Aragon) or in extremes he could put her in a convent. She could own no property in her own right and be reliant on her husband for her income and to pay her household’s wages. It’s a dire picture if we consider it from a purely legal standpoint. He paid for her clothes, her attendants, her food. He administered her lands for better or worse. There was nothing to stop him beating her and he could exercise his rights to her bed whenever he chose.

With this rather bleak picture of marriage, it’s hardly a wonder that the most common image of a period woman is one of oppression. A common theme therefore in historical fiction is the heroine balking at the idea of marriage and trying to assert her independence by marrying a man of her choice for love. The idea being, of course, that a man who loved her would never subject her to such a restrictive lifestyle.

To accept this view though, shows a very limited level of research. Yes, a husband was entitled to all of the above, but it doesn’t then follow that all men, or even the majority of men, became tyrants keeping their wives in constant penury. As a general rule, marriage was an equal partnership with husband and wife working together to advance their standing.

As a modern Western audience, we instantly sympathise with the bride trying to escape her arranged marriage. Inevitably, she represents the more modern ideals of marrying for love, and claiming her freedom, while her family usually insist on forcing through the bad match. In the BBC adaptation of The Other Boleyn Girl we have the family trying to marry off a young and attractive Mary Boleyn to an aged and overweight suitor purely out of Anne Boleyn’s spite. Again, just because a family could do this doesn’t mean they always would. The overwhelming majority matched a bride and groom of similar ages, or at least with a reasonable age gap.

We have an image of young girls being practically sold to rich and lecherous old men but this was a rarity and a potential scandal when it happened. When twenty-five year old Owen Tudor married twelve year old Margaret Beaufort, it wasn’t particularly noteworthy. When he then presumed upon his marital rights and actually got her pregnant, it was abhorrent that a man of his age had done such a thing to a child. When forty-nine year old Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, married fourteen year old Catherine Willoughby it was unusual enough that the Spanish ambassador included the news in his dispatches, such was “the novelty of the case.” It really wasn’t the norm and in cases that involved a young bride, she would usually live with her husband’s family until she or the couple were old enough to share a bed.

Kinship was all to the families of the Tudor court. Marriages were arranged in order to strengthen family ties and give themselves greater connections which would ensure mutual protection and prosperity. Sons had equally no say in their choice of their partner though they had the consolation that upon marriage they could do what they wanted with their potentially equally reluctant brides.

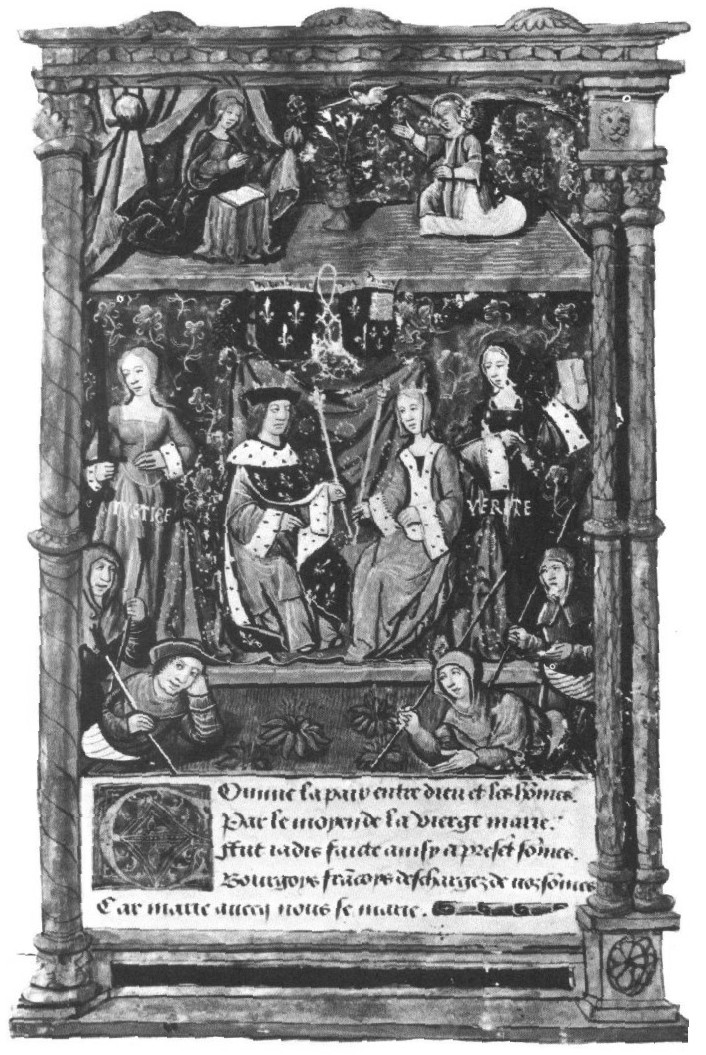

That said, the Tudor court was littered with women who made their own marriages in defiance of the wishes of their family, the monarch, and sometimes both. Princess Margaret, Princess Mary, both Anne and Mary Boleyn, Mary, Queen of Scots, Katherine and Mary Gray, Elizabeth Vernon, Elizabeth Throckmorton, Lettice Knollys… the list goes on but these are just some of the women who defied authority and married according to their own wishes. The very name Tudor comes from Henry VII’s grandmother, Catherine Valois, marrying her servant, Owen Tudor, in secret. When these marriages were discovered there was usually some fallout. Punishments ranged from banishment, disowning, fines, imprisonment, but a marriage was a marriage and while some of the couples were separated, they remained husband and wife.

Women were clearly and undeniably subordinate to men but this isn’t to say that they garnered no respect from society. In marriage, this respect was paramount. Legally, a husband owned their property but it often fell to the women to administer them as she did the household. As children, girls were sent to neighbouring households to learn such skills. The briefest of glances at the Lisle letters or the Paston letters will show women running estates without intervention from their husbands.

It was also a married woman’s purview to oversee the nursery, which among the upper classes did not involve actually nursing the children. They decided where, when, and how their children were educated. Marriages were made among mothers, often with fathers having as much input as to put his seal to it when the time came, assuming he hadn’t already granted his wife the legal power to do that without him.

As ever there were exceptions and in the worst case, a woman could take her husband to court for abuse and neglect. It wasn’t an easy process and divorces were rare and hard to come by but it was at least a theoretical possibility. Mary Talbot and Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland were quickly married in 1525/26 with neither particularly inclined towards the match. By 1528, the marriage had broken down completely and everyone knew it. Mary’s father feared that she was being abused which prompted Northumberland to lock her away and forbid her communication with her family, which reassured nobody. Mary however, retaliated by returning to her father and refusing to meet with her husband. She sued for divorce and had her request not hinged upon a precontract with a certain Queen Anne Boleyn, she may well have succeeded. As it happened, Northumberland died soon after anyway and Mary survived him by almost thirty five years in comfort. #Winning.

Another element of marriage in historical fiction is the wife neglected in favour of her husband’s mistress. This is especially popular in anything set in the Tudor period where we just need to look at Catherine of Aragon who “shut her eyes and endured” while her husband cavorted around the court with her ladies, culminating in his marriage to Anne Boleyn. While women (especially queens) were supposed to be virtuous the fact was many women did take lovers or live as the mistress of more powerful men. Anne Stafford, for one, lived in open adultery with William Compton until his death. It wasn’t the norm and invited scandal but it was something that happened. On the flip side, if a woman didn’t like her husband’s treatment of her over that of his lover, she had the ability to make his life very difficult.

All in all marriage was not the oppressive yoke some fiction would have us believe. While in theory men had complete control over their wives, in practice their wife was a partner to assist in the advancement of his ambitions and manage his domestic concerns. This is not to say of course that every wife enjoyed domestic bliss, but when fiction gives us a heroine flying in the face of her family to pave her own way with the man she loves, the alternative of an arranged marriage was not as abhorrent or restrictive as we may initially think.