Recently, I watched the 2008 film version of The Other Boleyn Girl. (Why, why did I do this to myself?) While musing on the sheer historical inaccuracy and wondering where Benedict Cumberbatch disappeared to halfway through the team, we came to a rather disturbing rape scene between Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. It’s a common theme in a lot of historical fiction to have Henry rape Anne, and this isn’t the first instance of it by far. There’s no historical evidence to suggest that Henry was ever violent towards Anne (execution notwithstanding) and so I ask myself, why do we keep seeing this distressing motif repeated in fiction?

In recent years Anne has received a far more sympathetic treatment from historians than her contemporaries ever gave her. Modern historians are generally in agreement that the label of ‘The Great Whore’ was undeserved. Recent biographies have moved away from the idea of a scheming woman using her body to ‘entrap’ the king and focused instead on her intelligence, wit and ambition. At the time those around her conceded, sometimes grudgingly, that what she was lacking in beauty she made up for in personality. George Wyatt praises her musical talents, her graceful dancing, education and the way she conducted herself in general. Anne Boleyn was, in essence, the perfect courtier so it’s not a surprise that she soon established herself as the most popular woman at court.

Despite the modern desire to consider Anne as a bright, intelligent woman we can’t just ignore the fact of her sexual appeal. Even though her dark looks were not as traditionally beautiful as the paler skinned, fair haired women Englishmen apparently preferred, we cannot deny that there was something quite obviously attractive about her. While her intelligence and learning maintained the interest of the king, this was coupled with some sort of physical attractiveness, whether it was her virginity, her sensuality or just her sheer self confidence. She wouldn’t have caught the king’s eye simply with her choice of reading material. Their earliest meeting is thought to have been the famous Chateu Vert which would become eerily prophetic; the masque being about a man’s desire for a woman who holds out against him but eventually relents allowing him access to her. Anne, ironically, was cast as Perseverance.As sexual as Anne may have been, we have every reason to believe that she was a virgin when she first slept with Henry. Although the court was riddled with flirtations and innuendo, Eric Ives suggests that the tradition of courtly love, despite the inherently sexual aspects of the game, would not have involved (as a general rule at least) any actual sexual activity. It was, after all, in place to govern courtship and allow potential partners to meet and get to know each other under the sanctions of chivalric tradition. While Anne certainly had her fair share of suitors and a rumoured betrothal with Henry Percy, later Earl of Northumberland, David Starkey dismisses the idea that they might have lain together, claiming that Anne would not have thrown away her reputation on a ‘potential’ match.

How then do we move from Anne the virgin to Anne the victim?

The poem ‘Who so list to hunt‘ by Anne’s contemporary and rumoured love interest Thomas Wyatt, presents us with the image of Anne as a hind hunted by the male courtiers, all competing to outdo each other and capturing her. While the poem adequately reflects Anne’s appeal at court and the attention she commanded, we cannot help but notice that the aim of the hunt was to capture and kill the hind, as Henry VIII, the winner of her affection, went on to do. But nothing contemporary suggests that Anne was the victim of a sexual assault.

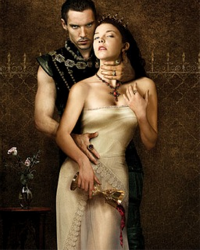

In modern films, Henry forces himself on Anne in Henry VIII (2003) and The Other Boleyn Girl (2008). Genevieve Bujold’s Anne refers to an assault in her younger years in Anne of the Thousand Days (1969), but it doesn’t form part of the main story. Henry VIII and The Other Boleyn Girl share many similarities in script (because they were written by the same man rather than because they drew from the same history) yet the violent scene is used for very different effect in both instances. In Henry VIII it is used to demonstrate the irretrievable breakdown in their relationship; Henry attacks her rather than continue an argument with her. As Anne is traditionally shown to be wilful and fiery-tempered the assault can be seen to show how Henry is unwilling to put up with her temper, preferring her instead to become a submissive wife. After leaving her, we see that Henry breaks down himself, trying to come to terms with what has happened to them as a couple. Other instances don’t tend to use it as a metaphor and wield it with far less subtlety. In the novel The Reincarnation of Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII forces himself on her because he can’t stand to think of her with another man. Following a similar theme in The Other Boleyn Girl Henry beds her against her will simply because he cannot restrain himself anymore.

During an argument, Henry tells Anne that he has broken with the church, sent Katherine, ‘a good woman’ away, and turned the country upside down to marry her, therefore she must consent to sleeping with him. When she refuses he simply has her anyway. In these cases, the assault, worryingly, is portrayed as a compliment to her. The compliment is one of possession; Henry wants her so much he is willing to force her and what woman wouldn’t be flattered by such attention. A description of Anne in the novel Brief Gaudy Hour presents her body as “a snare for any man” and here we have this confirmed on the screen. Certainly, in The Other Boleyn Girl we are given the impression that Anne has led Henry, and also herself, to this by teasing him but never giving into his advances.

Perhaps what is most worrying is that sometimes Anne falls pregnant as a result of the assault and goes on to birth Elizabeth. By the end of the film, Elizabeth is hailed as one of the greatest monarchs England has known and we are to forget that her mother was assaulted. In effect, the act is fully justified on-screen as Elizabeth I is the result and her mother was to blame by driving Henry to the act in the first place.

Thankfully this treatment of Anne Boleyn is limited in fiction and we can hope that it remains so. For the moment we, sadly, have just the few instances which largely portray it as something that is unavoidably Anne’s fault. The event is seen as the punishment for her ambition and the return she gets for holding out against the king by using her body as the ‘snare’ to trap him. Apparently, it is not enough that she lose her head in her quest for the throne, but she must be assaulted into the bargain; the price she pays for leading a man on.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.