BBC’s new historical drama,’The White Queen began on Sunday, with an impressive 5.3 million viewers tuning in to watch the whirlwind romance between Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville.

A great deal of modern historical fiction deals with Henry VIII and his choice of wives, but it is the commoners turned queen that command the most attention; Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Catherine Howard and Katherine Parr. It is not surprising then, to consider that the Plantagenets are to be the next historical family to grace our screens, after all, while to us the idea of a king marrying a commoner is now happily familiar, Edward IV did it first.

The affair between Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville is certainly one that can easily be dramatised, with very little fictional flourishes needed. In true Romeo and Juliet style, Edward was a Yorkist king, Elizabeth was a Lancastrian widow. Elizabeth’s first husband had recently been killed in a battle with Edward himself, leaving her largely destitute and dependent on the king’s charity. They were both young, attractive and new-come to the throne, a throne which was by no means secure and Edward would spend most of his life defending it, in a drawn out war that pitted cousins against each other. The White Queen has all the ingredients to make it a fascinating drama, without the need to add dramatic details and so far, that is largely what we have seen.

The Marriage

Historically, Edward and Elizabeth’s wedding was almost every bit as scandalised as the show has made out. They were almost certainly attracted to each other from the outset, the fact that in a nineteen year marriage Elizabeth birthed ten children suggests that there was a very real connection between the two.

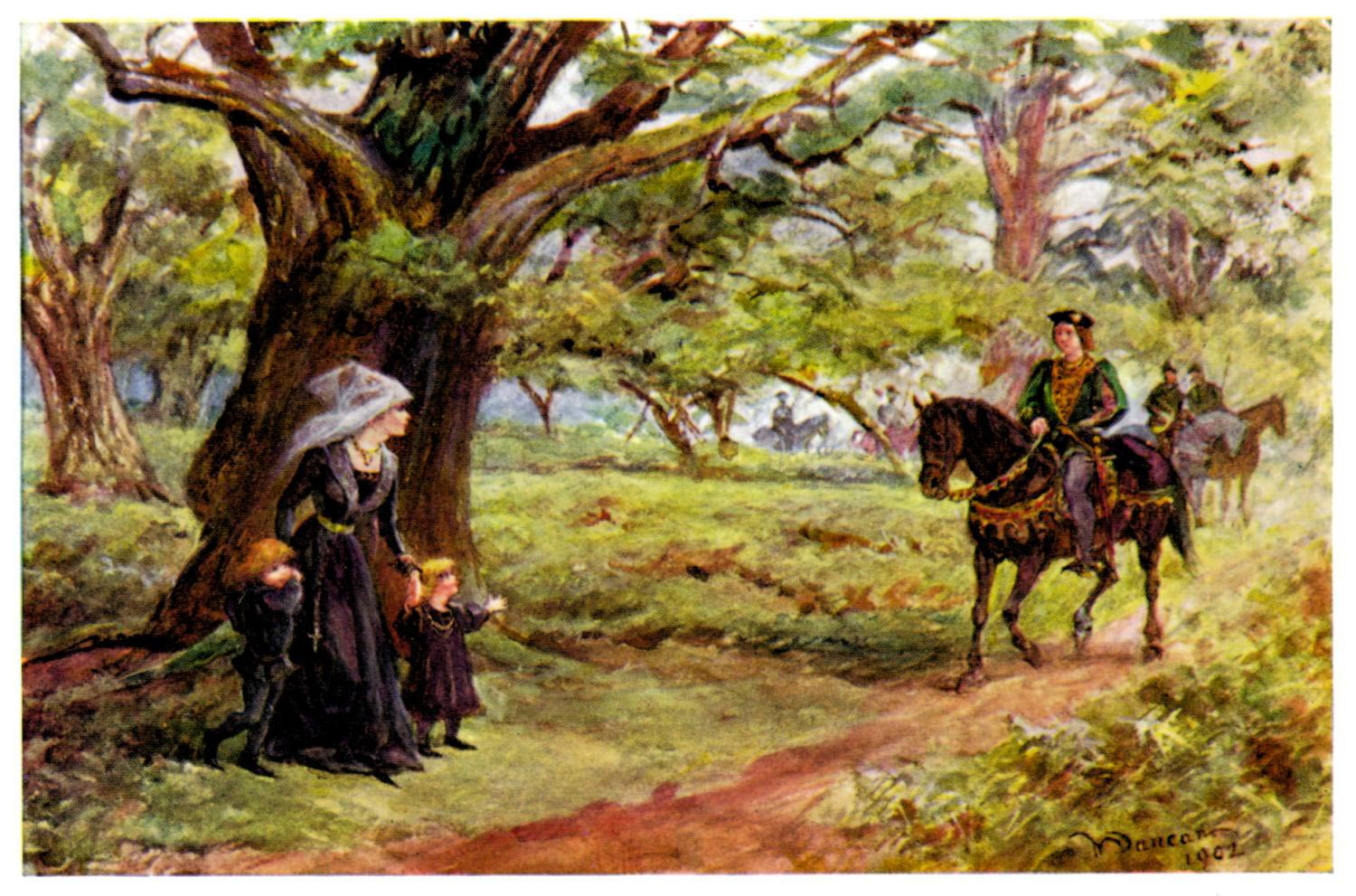

Their meeting under the oak tree at Grafton probably did not happen as literally as legend suggests. Edward IV was, somewhat surprisingly, already on very good terms with Elizabeth’s parents, despite their Lancastrian leanings. In the first year of Edward’s reign he gave them £100 for no especial reason, other than possibly taking a shine to their daughter.

Rather than waylay Edward on the road, we know that Edward was visiting her father and either through his or her mother’s introduction, Elizabeth, who would have already been known to the king in name if not in person, was among those who greeted him. Elizabeth was renowned for her beauty while Edward was famous for womanising. It is hardly surprising then, that Edward asked Elizabeth to become his mistress, historian David Loades (The Tudor Queens of England Continuum: 2009) claims that the story of her having to defend herself, against his attentions, with a dagger is certainly credible.

Obviously her refusals encouraged him, and Edward felt strongly enough about her to marry in secret, the first English king to marry at home, rather than a foreign princess. The news did not break until four months later and despite the initial disgruntled backlash, the marriage was accepted.

Accuracy vs Authenticity

So far there has been nothing wildly inaccurate and it seems that the greatest criticism has been one of authenticity rather than accuracy. Within minutes of the episode’s climax Twitter positively exploded with viewers pointing out mistakes, not in accuracy, but in appearances. While I would happily dismiss the few zips I noticed (and at one point Elizabeth Woodville’s microphone wire) to poor filming, other issues such as how clean the costumes were, the red brick houses and their twenty-first century speech have been accused of detracting from the realism.

In his review for The Telegraph, Gerard O’Donovan says that the show had ‘serious failings‘ as far as the history was concerned, ‘devoid as it was of any note of the hardship, chill and squalor of life in 15th-century England.’ And

this is certainly true. The costumes and surroundings are lavish, clean-cut and while this makes the series accessible, especially for the viewer with just a passing interest in the period, it also creates an atmosphere far removed from the period of the time. While Janet McTeer’s Jacquetta might refer to the notion that if Elizabeth were to marry the king, the rather large Woodville family would be provided for, there is no sense that without this patronage the family might struggle. There is no feeling of the constant hardships faced by courtiers dependent on royal favour to simply get by, or indeed any other hardships that might hinder the family.

As far as appearances are concerned, buildings with obvious double glazing and modern building materials just detract from the historical feel, which is surprising after the BBC announced the series was to be filmed in Belgium ‘to add to its authenticity.’ Ultimately it is hard to lose yourself in the period of the time, when there is very little of that period to get lost in.

This is not to say, however, that historical dramas should be made to look as utterly realistic as possible. It is a simple fact that having characters that hardly wash, with clothes incapable of being cleaned, living in houses that have human waste in the hallways will not be appealing to a modern audience. And that is not considering the lack of standardised English. Distracting modern speak might be, but it is at least understandable. I will just leave you with this Middle English excerpt from Psalm 23, you will see what I mean.

Lauerd me steres, noght wante sal me:

In stede of fode þare me louked he.

He fed me ouer watre ofe fode,

Mi saule he tornes in to gode.

He led me ouer sties of rightwisenes,

For his name, swa hali es.

Follow us on Twitter @HistoryRemaking