Picture credit: The Tudor Tutor

Reign, a period drama created for The CW, is two episodes in and is gaining a fair amount of mixed reviews. There are those who are quite happy to ignore the history behind the piece and enjoy the drama and entertainment value, while many are criticising the absurd acting and arguing that it is simply ‘bad’. This is of course not counting the various history buffs who are still picking bits of their brains off the wall from where their heads exploded from a complete lack of any historical accuracy. Reign is certainly creating a stir. As one reviewer put it:

Personally, I simply cannot make it out. I can’t hate it as a piece of historical work because it evidently takes little cues from history. It is certainly not the story of Mary, Queen of Scots, and is in fact, a shining example of an utterly fascinating woman in history completely fictionalised to make her ‘more interesting.’ In this instance the entire story of Mary, Queen of Scots and the setting of the French court have been repackaged to appeal to teenage girls, who apparently, according to the producers, cannot understand basic historical facts so everything has to be reduced to pulpy nonsense. Quite frankly this is more insulting than the poor script!

With such articulate gems as, “Francis had grave political objects what it meant to wed another country,” and, “We’re not telling Mary’s story … we’re telling a fictionalized accounting of Mary, Queen of Scots,” from the show’s executive producer, it really is no wonder that the story departs quite drastically from history. The costumes and setting are glamorised, looking less like a sixteenth century castle and more like a renaissance themed high school prom, an ambience not helped by the introduction of Mary’s four ladies in waiting, who all look inescapably modern. I understand that Mary having four ladies in waiting who were all also named Mary is probably confusing for a television audience. It was this prevailing logic which amalgamated the historical sisters of Henry VIII into the character of Margaret in The Tudors, lest Princess Mary Tudor be confused with Princess Mary, Henry’s daughter. This I can understand, but naming them Lola, Kenna, Greer and Aylee (names that I can assure you, are not contemporary) suggests that they aren’t taking themselves any bit as seriously as the reviewers seem to be.

I could write a very, very, very long post on the historical inaccuracies in Reign, but that would be wasting my time, because there is nothing accurate in it. So instead I will happily tell you about the actually, fascinating woman that was Mary, Queen of Scots. Why there was an attempted rape scene in the very first episode escapes me because Mary, historically, is thought to have been a rape victim. Why make up a scenario for something that might have happened? And with a man who existed! Her story is exciting enough without boiling it down to ‘herp derp sex, pretty dresses and boys’ which is apparently all that teenagers can identify with *facepalm*

Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary was born in Linlithgow, in the imaginatively named, Linlithgow Palace, the only child of James V of Scotland and his wife Mary of Guise on 8th December 1542. Six days later her father died leaving her the Queen of Scotland. Scotland was ruled by a regency council, though this was fraught with problems as there was a Catholic/Protestant divide among the lords and it often led to violence. Mary herself was betrothed to Henry VIII’s son, her cousin Prince Edward in her infancy, but this fell through and she was instead betrothed to the Dauphin of France. She set out from Dumbarton in 1548 at just five years old to live in France where she received an education befitting a future queen and ten years later she married the Dauphin, Francis at Notre Dame.

First Marriage

Henry II, King of France died the following year leaving his fifteen year old son and Mary to claim the thrones of France. Mary was also announcing herself as the Queen of England, something she had done since Mary I of England’s death in 1558. For many Catholics Mary, Queen of Scots was a legitimate alternative to the Protestant and illegitimate Elizabeth I. Her reign as Queen of France was short lived as just a year after she ascended to the throne her husband died leaving his mother in law as regent in lieu of his younger brother and Mary a young widow with little French prospects.

Despite the fraught political situation in Scotland and the fact that she had spent no time of significance there, Mary returned to Scotland where she took the throne and despite her deep mourning for her deceased husband, searched for a new husband. Numerous suits were entertained including one suggested by Elizabeth I that Mary marry Elizabeth’s favourite courtier Robert Dudley. As a Protestant and the most trusted of Elizabeth’s court (rumours of their own love affair notwithstanding) Elizabeth obviously hoped to control Mary, who, as Queen of a neighbouring power was a threat but as a rival claimant for the English throne was a continual annoyance. Mary eventually married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley who himself had a claim to the English throne through Mary’s grandmother Margaret Tudor, in the July of 1565, despite their consanguinity and vehement opposition from Elizabeth.

Second Marriage

Mary was apparently very much in love with Darnley though he soon revealed himself to be unstable. Her marriage was as unpopular among the Protestant factions of her court (Darnley was also a Catholic) as it was in England. In 1565 a number of Protestant lords led by Mary’s half brother, the Earl of Moray came out in open rebellion against the marriage, but after some short skirmishes Mary emerged triumphant.

Darnley was immature but also an alcoholic which exacerbated his tendency towards violence. He felt his title of ‘king consort’ was an insult and demanded he be made king completely which would give him the Scottish throne independent of his marriage. Though Mary’s refusal provoked him further she fell pregnant with a son; James who would become James VI of Scotland and I of England. By this time Darnley was involved in various conspiracies against his wife and in March of 1566, with a number of conspirators including the Protestant rebels he murdered Mary’s private secretary David Rizzio, in front of a pregnant Mary. Rizzio was a close friend of Mary, a friendship which had prompted rumours of infidelity on her part. Despite this, Mary reconciled with her husband and the rebels but the marital reunion was shortlived.

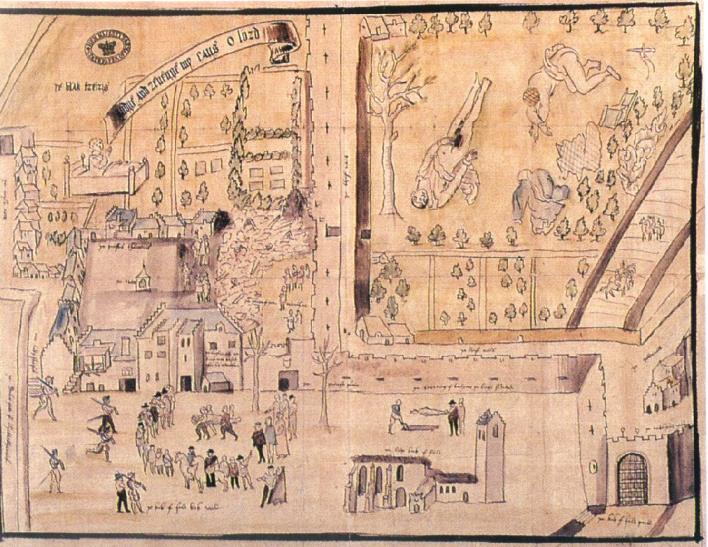

By the end of November Mary, and a number of nobles, met to discuss what could be done about Darnley whose behaviour was becoming increasingly unacceptable. Darnley fell ill towards the end of 1566 and at Mary’s request he recuperated near her, so she could visit him frequently. In early February 1567 an explosion destroyed the house in which Darnley was staying. His body was discovered in the garden, apparently thrown from the home in the blast, but there was evidence that he had been smothered and the explosion intended to cover up the murder.

Mary, a number of lords and in particular the Earl of Bothwell, a close friend of the queen, were all suspected of playing a part in the murder. Mary had been noted as visiting Bothwell while he recovered from injuries sustained during the Protestant rebellions and it was thought that he had designs on the throne. Bothwell was tried for the murder on the 12th April, but acquitted because of a lack of evidence. Shortly afterwards, Bothwell got written support from almost thirty lords and bishops for his suit towards the queen.

Third Marriage

The circumstances of Mary’s second marriage remain controversial and historians are still divided on the issue. On the 24th April Mary was traveling to Edinburgh when Bothwell, accompanied by eight hundred retainers, halted the journey, claiming that Edinburgh was dangerous and Mary would be safe at his nearby castle at Dunbar. Mary agreed, however upon her arrival Bothwell imprisoned and raped her, in an attempt to secure the crown. That she was imprisoned is undeniable, that she was raped is unknown but Bothwell was condemned for the act by contemporaries. What remains unknown is whether Mary was forced into this situation or whether she was a willing participant and the story of rape concocted to protect her honour when marrying a man she had been romantically linked with, just weeks after the same man was on trial for the murder of her husband.

On the 15th May, Mary married Bothwell at Holyrood, she also created him a Duke and lavished gifts upon him which destroyed some of her credibility in being an unwilling participant in Bothwell’s scheme and in turn divided the nobility. The lords opposed to the marriage met the queen and Bothwell in battle at Carberry Hill on 15th June 1567. Bothwell fled but Mary was taken to Edinburgh by the victorious lords. There she miscarried twins she had conceived by Bothwell and on the 24th July the lords forced her to abdicate giving the throne to her son James, at the time just a year old. She had not seen him since he was ten months old and she would not see him again for the rest of her life. Although imprisoned in the remote Loch Levan castle Mary managed to escape. She raised an unsuccessful army and fled south into England, where she expected Elizabeth I to assist her in regaining her throne.

Imprisonment in England

Needless to say Elizabeth did not assist Mary. Mary had antagonised Elizabeth with her claims to the throne of England and marriage to Darnley. It was preferable, given England’s fragile political and religious situation, that the Protestant regency continue in its rule over Scotland and upbringing of James VI.

Although Mary was imprisoned in Tutbury Castle she was still allowed a household and was kept in a manner appropriate to a visiting queen. Unfortunately the relative freedom allotted to her allowed numerous plots with the intention of either returning her to the Scottish throne or creating her queen of England, to form around her, prompting Elizabeth to curtail her allowances.

What followed was years of vacillation on Elizabeth’s part. Mary was too dangerous to return to Scotland, and in any case any attempt by Elizabeth to broach this possibility was blocked by the Protestant lords who had no desire to return a Catholic queen. Meanwhile keeping her in England proved to be dangerous in itself as numerous English courtiers plotted to replace Elizabeth with Mary, among them the Duke of Norfolk whose influence in England was considerable. The result was that those implicated in plots with Mary were executed while Mary repeatedly escaped punishment, not least because Elizabeth was extremely reluctant to execute an anointed queen, despite the entreaties of her courtiers.

Death

After eighteen years of purgatorial imprisonment in England, Mary’s activities came to a head after being implicated in the Babington plot in 1586. There is speculation that she was deliberately entrapped by Elizabeth’s spymaster, Francis Walsingham, who loosened the controls her jailor Amyas Paulet was imposing upon her, thus giving Mary the freedom to plot and Walsingham the opportunity to collate evidence. Mary was tried at Fotheringay Castle where she denied the charges with passionate defence. On the 25th October she was found guilty and sentenced to death by an almost unanimous decision. Elizabeth remained reluctant and though she did sign the death warrant the following February, she entrusted it to a low ranking councillor with the intention of keeping the warrant hidden for the moment. Two days later the Privy Council met and arranged the execution without Elizabeth’s knowledge or consent.

Mary was executed on the 8th February 1587. She was told the evening before and spent the time remaining to her in prayer. She wore red, the colour of Catholic martyrs, and was finally dispatched after three blows. When the executioner held up her severed head the hair came away revealing it to be a wig. Spectators were further confused by the movement in the body, which was revealed to be her terrier hiding in her skirts. Although Mary had requested a burial in France, Elizabeth instead had her interred in Peterborough Cathedral without any Catholic rites. In 1612 her son, James now king of England had her moved to Westminster Abbey where she remains in a chapel opposite that of Elizabeth.