The position of royal mistress, even a recognised maîtresse en titre was fraught with difficulties. The lucky, or perhaps more aptly, unlucky woman would have to work tirelessly to maintain the king’s interest. She would have to dispose of rivals without reducing herself to nagging the king or displeasing him in any way lest she herself be dismissed. Her political adversaries would be constantly trying to replace her and this was without the most basic demand of satisfying the king’s every whim. It is no wonder that some mistresses made bids for the throne, some successful others less so. At least as queen she was, in theory, unassailable or at the very least granted a measure of security her previous position would not have allowed her. Here we take a look at some of the women who tried to make the leap from first lady at court to first lady of the land, some of whom succeeded, others however were less than successful.

Inês de Castro

(1325-1355)

A Galician noblewoman, Inês Perez de Castro arrived in Portugal in 1340 to join the household of the recently married Constance of Castile. Constance had been married to King Afonso IV of Portugal’s heir Peter, though upon her arrival, he fell in love with Inês and immediately began neglecting his wife in favour of her maid. Their relationship had negative political implications as Peter’s treatment of Constance alienated an already fragile Castilian alliance while advancing Inês’ family. Afonso was satisfied that the relationship would run its course and while Peter still visited his wife’s bed enough to father their three children, he did not interfere.

A Galician noblewoman, Inês Perez de Castro arrived in Portugal in 1340 to join the household of the recently married Constance of Castile. Constance had been married to King Afonso IV of Portugal’s heir Peter, though upon her arrival, he fell in love with Inês and immediately began neglecting his wife in favour of her maid. Their relationship had negative political implications as Peter’s treatment of Constance alienated an already fragile Castilian alliance while advancing Inês’ family. Afonso was satisfied that the relationship would run its course and while Peter still visited his wife’s bed enough to father their three children, he did not interfere.

Five years later, Constance died shortly after giving birth to their third child and Peter refused to marry any of the women his father attempted to negotiate for, claiming that he would only marry Inês, with whom he would go on to have four children. Despite Afonso’s continued attempts to keep the couple apart, Peter defied his father and began living with Inês as though they were married. In 1355, while Inês was alone with her children, Afonso despatched assassins to kill her, which they did in front of her children, which infuriated Peter.

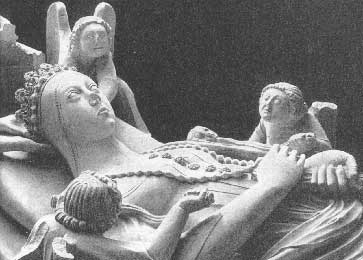

Peter led a brief revolt, but was reconciled to his father after his mother intervened. Though he gave the appearance of forgiveness, upon his accession to the Portugese throne in 1357 he had the assassins found, publicly tortured and executed. He then went on to announce that he and Inês had indeed been married in secret, though he could not provide a date, neither could the supposed witnesses. Despite only the king’s word on the matter the court had no choice to accept Inês’ posthumous coronation. Allegedly he had Inês’ body exhumed and crowned Queen of Portugal, forcing his court to kiss her hand, and legitimising their children together.

Anne Boleyn

(1501/7-1536)

The most well known ‘mistress’ to become queen, Anne Boleyn courted King Henry VIII of England for six years before he married her. Refusing to give up her virginity, Anne kept the King interested by making herself his indispensable courtier; advising him on politics, religion, matters of state while also entertaining him relentlessly and setting herself up as the most popular woman at court. Unlike many of the other mistresses who attempted to, or actually became queen, Anne Boleyn is unique for making her bid for the throne while Henry was still married to a queen who was neither sick nor dying. While Henry’s wife, Catherine of Aragon, after a lifetime of unsuccessful pregnancies and stillborn births was unable to have children, the notion that the King could successfully divorce her was bold to say the least. The Queen’s utter refusal to consent to such an act and the lack of foreign support meant that Anne was committed to her eventual marriage but without giving in to the demands of the King for far longer than anyone would have expected.

The most well known ‘mistress’ to become queen, Anne Boleyn courted King Henry VIII of England for six years before he married her. Refusing to give up her virginity, Anne kept the King interested by making herself his indispensable courtier; advising him on politics, religion, matters of state while also entertaining him relentlessly and setting herself up as the most popular woman at court. Unlike many of the other mistresses who attempted to, or actually became queen, Anne Boleyn is unique for making her bid for the throne while Henry was still married to a queen who was neither sick nor dying. While Henry’s wife, Catherine of Aragon, after a lifetime of unsuccessful pregnancies and stillborn births was unable to have children, the notion that the King could successfully divorce her was bold to say the least. The Queen’s utter refusal to consent to such an act and the lack of foreign support meant that Anne was committed to her eventual marriage but without giving in to the demands of the King for far longer than anyone would have expected.

Ironically, when she eventually gave into his physical demands before they were married she fell quickly pregnant, which facilitated the divorce and her marriage. Unwilling to allow a potential son to be illegitimate Henry and Anne were married in secret, followed by a more legal ceremony in January 1533. Although she attained the throne she was Queen for just three years, as Henry quickly lost interest in her after securing her as his wife. Her failure to produce an heir is thought to have been the catalyst which led to accusations of treason, witchcraft, incest and adultery which led to her execution one thousand days after becoming Queen.

Karin Månsdotter

(1550-1612)

Born to two commoners Karin made her court career beginning life as a waitress then a household servant before joining the court of the King of Sweden’s sister as a maid. In 1565 the King, Eric XIV of Sweden installed Karin as his official mistress, dismissing the number of women he was involved with at the time and treating their children as though they were his legitimate heirs. Karin can be considered one of, if not the first officially recognised, royal mistress of Sweden and Eric’s faithfulness to her was considered greatly unusual. So much so that Karin was suspected of witchcraft in bewitching him.

Born to two commoners Karin made her court career beginning life as a waitress then a household servant before joining the court of the King of Sweden’s sister as a maid. In 1565 the King, Eric XIV of Sweden installed Karin as his official mistress, dismissing the number of women he was involved with at the time and treating their children as though they were his legitimate heirs. Karin can be considered one of, if not the first officially recognised, royal mistress of Sweden and Eric’s faithfulness to her was considered greatly unusual. So much so that Karin was suspected of witchcraft in bewitching him.

Having failed to secure a marriage with a foreign princess, Eric secretly married Karin in 1567, though she was not recognised as Queen of Sweden, despite a formal wedding and coronation in 1568. Despite the rumours of witchcraft Karin was considered a gracious queen. Eric, however, was becoming increasingly unstable and eventually overthrown by his half brother in the same year as her coronation. Karin initially shared her husband’s imprisonment where she gave birth to two more children which forced their captors to separate them. She remained under house arrest until her husband’s death in 1577, upon which she was released. Karin was allowed to live in the royal palaces in Finland, where she became much loved and respected.

Catherine Henriette de Balzac d’Entragues

(1579-1633)

The daughter of a royal mistress herself, Henriette d’Entragues, caught the eye of King Henri IV while he was grieving for the death of his beloved, long term mistress; Gabrielle d’Estrées. In fact at the time of Gabrielle’s death Henri was preparing to marry her, her sudden death after delivering a stillborn son left him utterly devastated. Henriette took advantage of these circumstances, pushing herself to the centre of Henri IV’s court and replacing Gabrielle in his affections.

The daughter of a royal mistress herself, Henriette d’Entragues, caught the eye of King Henri IV while he was grieving for the death of his beloved, long term mistress; Gabrielle d’Estrées. In fact at the time of Gabrielle’s death Henri was preparing to marry her, her sudden death after delivering a stillborn son left him utterly devastated. Henriette took advantage of these circumstances, pushing herself to the centre of Henri IV’s court and replacing Gabrielle in his affections.

While Gabrielle had been known as sweet and affectionate, Henriette was grasping and tempestuous. Before she surrendered her virtue to Henri she demanded the outlandish sum of one hundred thousand crowns, which was granted. Henriette had two children by Henri, one of whom was legitimised. She demanded that he marry her and secured a note written in his own hand, promising such terms, even though at the time he was involved in negotiations to marry Marie de’ Medici. She was not humble in her achievement however, flaunting the letter in the face of the scandalised courtiers. Henri did not honour his promise, and instead married Marie, causing Henriette to fly into a rage, even though at the time she was heavily pregnant.

Although exhausted by her tantrums, she remained Henri’s mistress, falling pregnant at the same time as his new queen. They both delivered sons within weeks of each other, but the King was overjoyed with Henriette. Later when the Queen delivered a healthy daughter Henriette followed some weeks later with a daughter of her own. She was expected to serve the Queen as a lady in waiting yet was continually disrespectful towards her, which prompted the Queen to try and rid her from court. Henriette was too popular with the King and instead her attempts only alienated herself from her husband. Henriette would cause her own downfall in 1608 when she involved herself in a Spanish plot to place her legitimised son on the throne. When Henri died two years later, Marie immediately exiled Henriette from court where she would remain until her death in 1633.

Françoise d’Aubigné

(1634-1719)

The widowed and penniless Françoise d’Aubigné was preparing to undertake a journey to Lisbon where she would take up a position as a lady in waiting to the Queen of Portugal, when a chance meeting with a Madame de Montespan secured her a position closer to home, at the French court. The beautiful, yet cold, Madame de Montespan was the secret mistress of Louis XIV and took an immediate like to Françoise, convincing the King to give her a pension and offering her a position looking after their illegitimate children, when they came. Françoise was an extremely pious and older woman, thus Madame de Montespan did not consider her one of the rivals for the King’s affections, especially as the former insisted on dressing in mourning clothes for her husband and garnished them with only the minimal amount of jewelry, mostly made up of crucifixes.

The widowed and penniless Françoise d’Aubigné was preparing to undertake a journey to Lisbon where she would take up a position as a lady in waiting to the Queen of Portugal, when a chance meeting with a Madame de Montespan secured her a position closer to home, at the French court. The beautiful, yet cold, Madame de Montespan was the secret mistress of Louis XIV and took an immediate like to Françoise, convincing the King to give her a pension and offering her a position looking after their illegitimate children, when they came. Françoise was an extremely pious and older woman, thus Madame de Montespan did not consider her one of the rivals for the King’s affections, especially as the former insisted on dressing in mourning clothes for her husband and garnished them with only the minimal amount of jewelry, mostly made up of crucifixes.

While initially, Louis vocally disapproved of Françoise’s appearance he could not fail to notice the love and care which she lavished on his children, while their disinterested mother resorted ever more frequently to tempestuous outbursts. Louis would reward Françoise for her diligent efforts with a grant of money which she used to purchase a house at Maintenon, prompting the King to create her Marquise de Maintenon which incurred the wrath of Madame de Montespan, even though Françoise refused to become Louis’ mistress.

After a rather spectacular downfall on Madame de Montespan’s part (she was found to have poisoned her lover with the remains of child sacrifices amongst other horrific crimes), Françoise became his recognised mistress though she cultivated the friendship of his Queen whom she encouraged Louis to respect.

The two were married two or three years after the Queen’s death, though Françoise was never crowned nor recognised as the Queen of France. She did exercise political power, however and was responsible for a great deal of political dealings behind closed doors. After her husband died in 1715 she retired to Saint-Cyr where she lived until her own death four years later and was buried in the same place, having lived comfortably off the pension provided by the new King.

Marie Emilie de Joly de Choin

(1670-1732)

Unlike many mistresses who were ladies in waiting to the king’s wives, Marie was lady in waiting to King Louis XIV’s favourite, albeit illegitimate, daughter. While there, Louis’ heir the dauphin, another Louis, fell in love with her even though she was considered quite ugly for the time. After Louis’ wife died she became his mistress, even though she was already having an affair with a Count from Luxembourg. The lovers devised a plan which would have given them eventual power over the French throne, though both were banished from the court when their coup was discovered, but Louis remained infatuated with Marie and their relationship continued.

Unlike many mistresses who were ladies in waiting to the king’s wives, Marie was lady in waiting to King Louis XIV’s favourite, albeit illegitimate, daughter. While there, Louis’ heir the dauphin, another Louis, fell in love with her even though she was considered quite ugly for the time. After Louis’ wife died she became his mistress, even though she was already having an affair with a Count from Luxembourg. The lovers devised a plan which would have given them eventual power over the French throne, though both were banished from the court when their coup was discovered, but Louis remained infatuated with Marie and their relationship continued.

The two were secretly married, though she did not receive the estate expected of a Dauphine. Instead she lived on a comparatively meagre pension, made all the more so by her miserly husband. She did not take on any additional titles, lands, revenues or even involved herself in the political life. To her credit Marie did not avail herself of any of the privileges of her position and though she was legally Louis’ wife, she did not make any outward display of royalty, though she entertain the court and visiting dignitaries. In 1711 Louis died before his father, thus the couple did not take the thrones of France. Despite being left a fortune by her husband, Marie refused it and instead retired to live a private life off a meagre royal pension, where she was praised for her quiet living.

Catherine Dolgorukov

(1847-1922)

Catherine first attracted the attentions of Tsar Alexander II of Russia in 1864, when she was just sixteen years old and still in school. Alexander was married with six children as well as having fathered a number of illegitimate children with at least three different mistresses. Despite her age the two became inseparable though not physically intimate until 1866 after which Catherine remained in close proximity to her lover and would have four children.

Catherine first attracted the attentions of Tsar Alexander II of Russia in 1864, when she was just sixteen years old and still in school. Alexander was married with six children as well as having fathered a number of illegitimate children with at least three different mistresses. Despite her age the two became inseparable though not physically intimate until 1866 after which Catherine remained in close proximity to her lover and would have four children.

Although she did not engage in politics, outside of having liberal opinions, the relationship was heavily disapproved of. Alexander had a fear of assassination, which given how often attempts were made on his life was unsurprising, so he had Catherine and their children moved into his own household shortly before his wife’s death. He then scandalised his family by marrying Catherine just thirty days after his wife, the Empress Maria, died, though he did not give her the title of Empress. Their children, though legitimised, were not given any rights to the throne. Despite these measures, Alexander’s family and the Russian court still feared that Catherine intended to put her own children on the throne. The marriage, however happy, was short lived as Alexander was assassinated the following year. His body, torn apart (literally) by an explosion, was brought back to their home where he died in Catherine’s arms. The family continued to alienate her, so much so that she and their children were forbidden entry to the funeral and they had little to do with her after she retired to France where would live for a further forty one years.

Wallis Simpson

(1896-1986)

Unlike most mistresses whose main obstacle to the hand of the king was his wife, Wallis Simpson’s controversial problem stemmed from the fact that she herself was married, rather than her lover. Wallis was introduced to the then Prince of Wales, Edward, in 1931 by his mistress Lady Furness. Although she was at the time married to her second husband, she became his mistress in 1934, quickly securing his affections and isolating him from his former lovers. Their relationship is thought to have been one of domination on her part, as Edward seemed unusually devoted to her. He lavished gifts of money and jewels upon her and spent a considerable amount of time in her company, neglecting his royal duties and causing friction within the royal family by insisting that their relationship was platonic, despite evidence to the contrary.

Unlike most mistresses whose main obstacle to the hand of the king was his wife, Wallis Simpson’s controversial problem stemmed from the fact that she herself was married, rather than her lover. Wallis was introduced to the then Prince of Wales, Edward, in 1931 by his mistress Lady Furness. Although she was at the time married to her second husband, she became his mistress in 1934, quickly securing his affections and isolating him from his former lovers. Their relationship is thought to have been one of domination on her part, as Edward seemed unusually devoted to her. He lavished gifts of money and jewels upon her and spent a considerable amount of time in her company, neglecting his royal duties and causing friction within the royal family by insisting that their relationship was platonic, despite evidence to the contrary.

In January 1936 King George V died, leaving Edward as Edward VIII to hear his proclamation in the company of Wallis. They continued to spend their time together while rumours circulated that Edward intended to marry her, something which the British court and government felt was completely unacceptable, though the idea was popular in Wallis’ native America. Wallis filed for divorce from her second husband in October 1936, rather ironically on grounds of adultery on his part. With the prospect of the marriage suddenly very real, the government was forced to intervene.

Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin and others were involved in negotiations with the king where they tried to convince him, unsuccessfully, out of the match. Wallis’ position as mistress was only partially the issue. Far more problematic was the fact that she had two living husbands, while the Church of England (of which Edward was the head) did not recognise divorce. In the face of this, her sexual relationship with the King as well as other gentlemen at the same time, were the tip of the iceberg.

Left with the choice of his throne or the woman he loved, Edward abdicated and the two were married shortly after Wallis’ divorce was confirmed. They were granted obligatory titles of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor though Wallis was barred from using the styling ‘Her Royal Highness’. The two went to live in France where they remained unpopular in Britain for their Nazi sympathies. Although they were married until the Duke’s death in 1972, they were thought to be unhappy. They were never accepted by the royal family, and it was thought that Wallis’ ambition for the throne was greater than her love for Edward but that they were forced to remain together because of the lengths they had gone to to get married. In her widowhood, supported by her late husband’s estate and an allowance from the Queen, Wallis was increasingly plagued by ill health before she died herself in 1996.