Unlike most of the posts I write, this one is not tied into something in modern media, I just happened to be researching prostitutes (as one does), and thought I’d share because it’s my blog and why not? Ha!

Researching prostitution during the Middle Ages is not an easy ask, particularly in Medieval England. Prostitution was not necessarily a woman’s sole career choice and there are many examples of women who used prostitution to supplement their everyday income. A lack of centralised law across England provides a consistently different attitude towards prostitutes across the country, an attitude which was already significantly different to that on the continent. As a general rule Europe seemed to be far more lenient and accepting of the occupation as a necessary public utility and, although many countries engaged a policy of restriction, it was aimed against the clientele of the prostitutes and not the prostitutes themselves. In particular married men, clergy and Jews were forbidden to patronise them and faced heavy fines if caught doing so, while the admitting brothel faced no repercussions for allowing them entry.

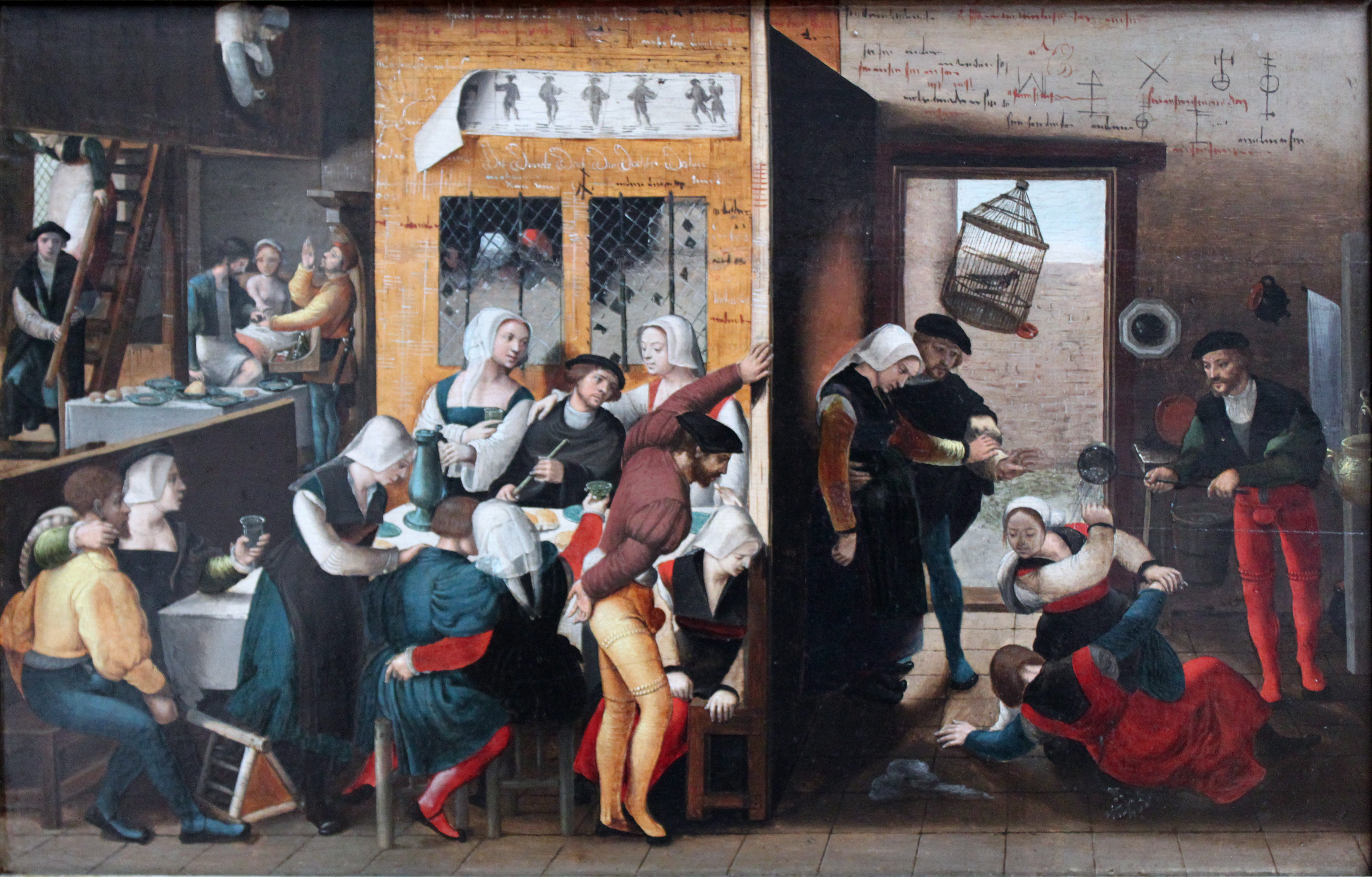

In early Medieval France prostitutes faced public humiliation in an attempt to repress the trade. However, in later centuries there developed a clear recognition that men, especially those who were unmarried had needs. In recognising these needs the authorities also saw how money could be made from providing them with the necessary services, and so public brothels, managed by town officials came into being. Providing they paid a weekly sum to the authorities these women were allowed to ply their trade without interference or harassment. The rest of Europe was largely tolerant of sex workers. The rationale being that allowing brothels to operate accorded the authorities some level of control over the industry, created specific areas where men could go to indulge discreetly, protected innocent women and limited the disruption caused by prostitutes who advertised themselves in the street. The idea of publicly operated brothels never caught on in England, which maintained a negative attitude towards the occupation and punished anyone involved; the women themselves, those who allowed it to operate and the clients. England had more prosecutions for prostitution than any other European country, even more than certain areas of Italy which had outright banned the trade.

The medieval prostitute almost never undertook her occupation to sate her uncontrollable lust, the motivation was almost always financial. While there were a number of full time prostitutes, there were also women who simply used it as a means to bolster their primary source of income during particularly hard times, more disturbingly there were those women who were sold by their family members in order to generate funds for the family. As there was no strict definition of what constituted a prostitute, there was also a lack of consistency in the legal treatment of them. While in London the area of Stewside was unofficially designated the medieval equivalent of the Red Light District, in Coventry any single woman renting a room for herself could be arrested under suspicion of prostitution, which prompted the authorities to outright ban single women from renting rooms. In towns where prostitution was rife but uncontrolled, any woman wandering the streets after dark was presumed to be available for sale and cases of mistaken identity resulting in violence were common. As such numerous towns/cities demanded that prostitutes dressed themselves in specific clothes to distinguish themselves from the general populace, with most requiring the ladies to don a striped hood. Particularly successful whores found themselves prosecuted for breaching sumptuary laws (laws which restricted the clothing – colour, material etc, that certain classes could wear) rather than the act which earned them the money for the finery in the first place.

The punishment of prostitutes across England reveals a lack of concerted effort to deal with the “problem” and more a series of superficial measures meant to act as mild deterrents, rather than to eradicate prostitution completely. In Southampton a number of women pooled their resources and all moved to the same street to rent rooms from where they could sell themselves. They seemed to have operated there for a number of years before the local religious community made a particularly loud complaint forcing the authorities to move the women on, but they faced no actual punishment. The most common sanction found in the town ordinances across England, involve the town bailiff removing the doors and/or windows of the woman’s home rendering it uninhabitable and certainly an unattractive place for a potential rendezvous. Later this would be replaced by more obvious methods of public humiliation where the woman was taken outside of the city walls and expelled. Pimps or brothel owners also faced public humiliation but were also at risk of the more severe punishments of fines and prison sentences.

During the later medieval period the Christian notion of the ‘reformed prostitute’ took hold, fueled by the cults of Saint Mary of Egypt and Mary Magdalene, and public opinion softened towards whores. Instead of being women to be reviled, these women were now the subject of charity, and public funds were set up to assist women trying to escape a life of sex work. Despite this in many areas women known to sell their bodies were not allowed membership of their local church until they had set aside their life of sin, though we should also point out that there are numerous, numerous records of churchmen being caught with prostitutes. The punishment for which was severe (for the churchmen). All in all the attitude towards prostitution was entirely contradictory. On one hand they were a necessary utility required (and approved of) to provide a service for unmarried men while on the other they were peddlers of sin, needing to be expelled from the city lest they sully the reputation of a town by their deeds. Better indeed to have been a prostitute in Europe and enjoy an interference free, entirely legal life, albeit at a price…

Selected Bibliography

Printed Primary Sources

Trans. Henry Thomas Riley, Liber Albus: The White Book of the City of London, (John Russel Smith 1862)

Trans. & ed. P.J.P Goldberg, Women in England 1275-1525, (Manchester University Press, 1995)

Secondary Sources

P.J.P. Goldberg, Women, Work and Life Cycle in a Medieval Economy, (Clarendon Press, 1992)

Henrietta Leyser, Medieval Women: A Social History of Women in England 450-1500, (Pheonix, 2002)

James A. Brundage, Law, Sex and Christian Society in Medieval Europe, (University of Chicago Press, 1987)

Ruth Mazo Karras, Common Women: Prostitution and Sexuality in Medieval England, (Oxford University Press, 1998)

Edith Ennen, The Medieval Woman, (Basil Blackwell Ltd, 1989)

James A. Brundage, ‘Sex and Canon Law’ in Handbook of Medieval Sexuality ed. Vern L. Bullough and James A. Brundage (Garland Publishing, 1996) pp 33-51

Ruth Mazo Karras, ‘Prostitution in Medieval Europe’ in Handbook of Medieval Sexuality ed. Vern L. Bullough and James A. Brundage (Garland Publishing, 1996) pp 243-261

Barbara A. Hanawalt, ‘The Female Felon in Fourteenth Century’ in Women in Medieval Society, ed. Susan Stuard (The University of Pennsylvania Press, 1976) pp 125-141

Ann J. Kettle, ‘Ruined Maids: Prostitutes and Serving Girls in Later Medieval England’ in Matrons and Marginal Women in Medieval Society ed. Robert R. Edwards and Vickie Ziegler (The Boydell Press, 1995) pp 19-33

P.J.P Goldberg, ‘Women’s Work, Women’s Role in the Later Medieval North,’ in Profit, Piety and the Professions in Later Medieval England ed. Michael Hicks (Alan Sutton Publishing, 1990) pp 34-51

Jane Tibbetts Schulenberg, ‘Saints’ Lives as a Source for the History of Women 500-1100’ in Medieval Women and the Sources of Medieval History ed. Joel T. Rosenthal (The University of Georgia Press, 1990) pp 285-321