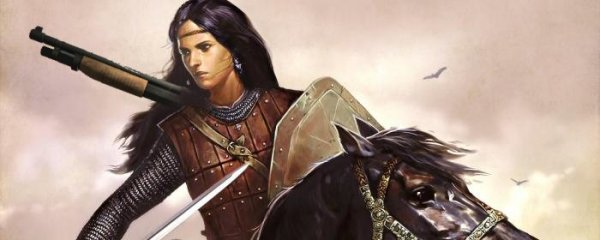

I’ve written before about how the games Mount and Blade and its sequel, Warband, are a, shall we say challenging, experience for the female character. Set in the fictional kingdom of Calradia during the 13th century this ARPG is practically a medieval simulator. After statting up your character you can go on to raise an army, gain support from neighbouring lords, engage in political intrigue, manage fiefs, I could go on. Hell, maybe I will; protect your villages from bandits and raiding parties, keep you army fed, protect your king’s interests, garrison castles, maintain your household, and I’ll stop now, you probably get the picture. The game is praised for its realism and the believable way in which society is presented (altered somewhat to make a fun video game). As the medieval world was dominated by men, the game is that much harder ot play as a female character, something which the game warns you of when you choose this option. As a woman you are faced with a struggle to be taken seriously, even after you have distinguished yourself many times over. Your dialogue options with other women especially, are extremely limited. Whereas men can befriend noblewomen which can then prompt them to work in their favour, increasing their relationships with other lords, dialogue between two women is limited to; who are you and where is your husband? If you want to impress a lord you have to do it yourself which in itself is harder as a woman.

In Calradia, while women are not unheard of as soldiers they are generally confined to a domestic sphere the latter of which accurately reflects the medieval world. There are almost no mentions of women acting as soldiers or leading armies in the medieval West, but that would make for a very short video game if you showed up and were immediately told to go home.

In Calradia, while women are not unheard of as soldiers they are generally confined to a domestic sphere the latter of which accurately reflects the medieval world. There are almost no mentions of women acting as soldiers or leading armies in the medieval West, but that would make for a very short video game if you showed up and were immediately told to go home.

Women of the time were restricted by law in many ways. As a general rule they could not hold their own land, or for that matter anything of their own. Their wealth and property was owned on their behalf by their father until they married upon which it became the concern of her husband. There were of course exceptions; heiresses and widows could manage their lands in their own right and be considered the legal owner. Those who argue that women were oppressed during this time point to the heiresses and widows who were forced to marry by their male relatives so that they could claim her wealth for their own, and such things did certainly occur. But they were the exception rather than the rule. If a widow or an heiress was to marry again, she was perfectly capable of arranging her own marriage if she so desired a husband.

Although a noble or gentry woman’s sphere of influence was mostly domestic this in turn gave them a considerable amount of power. While in the strictest legal sense a woman had little power and must defer, in all matters, to her husband, in practice this was simply not the case. We can liken it to underage drinking laws here in the UK, where it is illegal to drink alcohol under the age of 18. And if you can find me an underage teen who hasn’t imbibed alcohol I’ll buy you a drink (providing you’re old enough to drink it). The point is that future generations would be mistaken to look back and claim that nobody ever drank alcohol under the age of 18 because the law told them not to. While the law may have said a medieval woman was subservient to the whims of her husband this did not mean that every man kept his wife in a state of constant autocratic subjugation. Marriage was very much an equal partnership. Women were indeed “limited” to a domestic sphere but to dismiss that as irrelevant grossly underestimates the demands of medieval domesticity.

When we think of running a household our mind summons images of menu planning with the cook, making sure the masters shirts are ironed and other such placating tasks. But the medieval woman was the mistress of the household not the housekeeper. The image of wealth was everything so the household had to convey the appearance of luxury and there were numerous tasks involved in keeping the household runnning at considerably less expense than would ever have been let on. Amongst other things she kept the properties clean and presentable, kept the larders stocked for the best price, she managed the servants, tenants and any other employees attached to their land. She was responsible for the family’s relationships with everyone in a world where ‘it’s not what you know but who you know’ was absolute. To that end she arranged the education of her children with the children of other nobles in order to network early on, she would arrange their marriages to advance the family’s standing, while also hosting the children of other nobles to further their own education. While her husband would technically need to approve these decisions, the household was very much the woman’s domain and she an essential part of its running.

A letter from Margaret Paston to her husband dated from the 15th century, reveals that she has equipped the garrison of their home with crossbows so that they can better defend themselves. Meanwhile letters from Honor de Lisle dated to the following century, shows how she solely managed to place one of her daughters in Queen Jane Seymour’s employ after sending the pregnant Queen some quails to satisfy her cravings. Having a daughter in the Queen’s service guaranteed the Lisles an inside view of the court while potentially gaining the ear of the Queen and so by extension; the king. The former was solely responsible for the safety of her home, while she might write to her husband to inform him of her decision she does not ask his permission or opinion, she simply acts where she sees fit. In the latter we see a woman engineering a situation whereby she can advance the family, without any input from her husband. In fact, it is doubtful he was even told of what was going on until his daughter was already installed as a lady in waiting.

A letter from Margaret Paston to her husband dated from the 15th century, reveals that she has equipped the garrison of their home with crossbows so that they can better defend themselves. Meanwhile letters from Honor de Lisle dated to the following century, shows how she solely managed to place one of her daughters in Queen Jane Seymour’s employ after sending the pregnant Queen some quails to satisfy her cravings. Having a daughter in the Queen’s service guaranteed the Lisles an inside view of the court while potentially gaining the ear of the Queen and so by extension; the king. The former was solely responsible for the safety of her home, while she might write to her husband to inform him of her decision she does not ask his permission or opinion, she simply acts where she sees fit. In the latter we see a woman engineering a situation whereby she can advance the family, without any input from her husband. In fact, it is doubtful he was even told of what was going on until his daughter was already installed as a lady in waiting.

In this regard Mount and Blade: Warband has it spot on. One of the easiest ways to increase your standing with the other nobles is to host a feast, something which your wife arranges providing she is given the necessary items to do so (food and drink etc). In my case, playing as a woman, I can suggest to my husband that we should host a feast, which he will agree to and then promptly hand the whole thing over to me. I may be but a woman but that by the standards of the time I am an organisational legend. So while historically and legally a woman could do little, in practice, although she had to marry, marriage was an equal partnership. On her part because that was the sphere in which she had the greatest influence, on his part because to offend your wife had considerable ramifications. True, there are stories of women who offended their husbands and suffered for it. He could leave her penniless or imprisoned and these stories are not to be discounted and some women did, of course, suffer at the hands of their husbands. But this was of course, the exception rather than the rule. Although a woman didn’t have the power to hurt his person an offended wife could potentially ruin him socially. So much so that there are instances of monarchs involving themselves in marital disputes where the husband and wife were at odds, because their arguments could disrupt the kingdom.

My character in Mount and Blade actually has a lot to be thankful for in regards to her marriage. She has married a noble’s son even though she has no property to offer in way of a dowry. With the exception of organising feasts she offers little in the way of domesticity, though maybe she would be more inclined to if she and her husband actually had a castle to call home. Meanwhile the other wives can supply their husbands’ army with food and keep the home fires burning, my character is off trying to win wars as a mercenary to fund her grain business.

I regret nothing.