While we know her as the ‘Nine Day Queen’, Lady Jane Grey would probably have passed into history as an irrelevant, albeit intelligent, Tudor cousin had it not been for the ambitious machinations of John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. Having schemed his way to the position of Lord Protector during the reign of young Edward VI, Northumberland spied an opportunity to increase his power base when the young king fell ill with no signs of recovering, and it extended slightly further than sending Mary Tudor a fruit basket. Aware that his power would have been severely curtailed if the Catholic princess Mary succeeded to the throne, the fervent Protestant Northumberland executed a coup to place Jane Grey on the throne. The coup was short lived (lasting only nine days in fact) though Jane Grey is still included as a monarch of Britain despite her brief tenure.

Because Jane’s reign was a short (very short) interlude between the reigns of Edward VI and Mary I, those nine days are usually glossed over despite the eventful political and military maneuvering that occurred. So I’ve dug deep and complied a chronology of Jane’s ill-fated reign (10th July-19th July).

The Claim

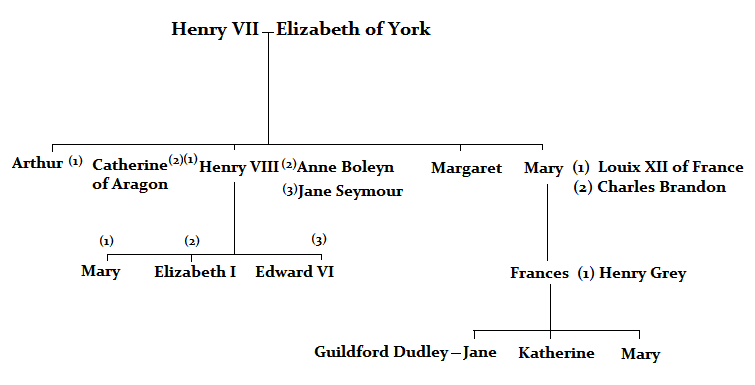

Jane’s claim to the throne was affirmed in the 1544 Act of Succession, in which Henry VIII named the Grey family (through Mary Tudor’s daughters by Charles Brandon) his successors after his daughters Mary and Elizabeth (who remained illegitimate).

Jane was born in October 1537, the same year as her royal cousin Edward VI, but despite their similar ages, they had little relationship growing up. When Edward became king in 1547, Jane joined the household of Katherine Parr, alongside the Princess Elizabeth. Yet, they too would remain seemingly indifferent to each other. Their closeness in age, blood relationship and the fact that were living and being educated together should have created at least a passing friendship but neither girl seemed to have shown any affection towards each other, save for the obligatory Christmas gift. Neither did they seem to shed any tears for the loss of the other’s company when they parted after Katherine Parr’s death. Though her husband, Thomas Seymour, initially intended to keep her household together, that notion ended pretty quickly along with his life, when he was executed for treason. Jane returned to her parents’ home, but clearly didn’t enjoy the experience, describing their company to even the briefest of visitors as “hellish.”

She was still living at home when Edward began to show signs of ill-health in 1552. By now, John Dudley had overthrown the previous Lord Protector and elevated himself to the Dukedom of Northumberland. Although genial towards the Princess Mary, her refusal to embrace religious change and her strict adherence to the Catholic faith of her mother had brought her into repeated argument with the throne. While she might have been the obvious, expected and indeed legal heir, she was not Northumberland’s first choice. Therefore, he decided, overlooking the not so fine print in the Act of Succession, she would not inherit. While it would have been preferable to place Elizabeth (the Protestant princess) on the throne, politically and legally it would have been a great deal harder to disinherit one sister for the other, than to simply disinherit both in favour of a new claimant. Northumberland’s eye fell on young Jane Grey who had numerous qualities endearing to a scheming noble; she was legitimate, she had a blood claim, she would be supposedly pliable given her age and for bonus points, she wasn’t Catholic. The fact that Edward VI already approved of her succession was really just the icing on top of a Jane Grey shaped cake.

Within a year Jane was married, against her wishes, to Northumberland’s son Guildford Dudley on 25th May 1553. By this time Edward had already drafted his own device for the succession, excluding his sisters without their knowledge and conferring the throne upon Jane, also without her knowledge. While Jane was kept deliberately in the dark, along with the rest of the court, and indeed England, she was probably astute enough to understand the implications of marriage with the Lord Protector’s son.

Edward died shortly after the wedding, on 6th July 1553, yet Jane’s reign would not begin until the 10th, four days later. During this time, Edward’s body was left unattended in his room, while Northumberland, further garnering an historical reputation as less than a stand up guy, suppressed all knowledge of his death.

Jane the Quene

Sunday 9th July

Although not counted as one of her nine days, it was on this day that Jane was informed that she was now Queen.

Jane was at Chelsea House when her new sister in law, Mary Sidney, fetched her to Northumberland’s house at Syon. There she was surprised to find Northumberland as well as numerous Earls and nobles.

While she was apparently taken aback when they started kneeling and kissing her hand, she was positively overcome when they informed her of Edward’s death and declared her the Queen of England. So much so, that she protested her inadequacies and fell to the ground, half-fainting, half-weeping. When it became clear that it didn’t matter how Jane felt about the matter and that she was indeed Queen, she started praying fervently and was given a night to come to terms with her new state. No doubt Northumberland had pre-empted the scene and had hoped she would recover sufficiently to face the public the following day.

Monday 10th July – Jane’s reign begins here

Jane and Guildford (the latter particularly well turned-out) were taken by river to the Tower of London in full royal state, much to the confusion of the common folk who had expected a more Mary Tudor-esque queen to succeed Edward. To further confuse matters, it was Jane’s mother who acted as the new queen’s train bearer, but as it was through her mother that Jane’s claim came in the first place, the natural assumption would be that it was she who would accede the throne. Northumberland had apparently struck a deal with the Suffolks, agreeing that Jane’s mother Frances would forego her claim in favour of her daughter’s.

As Jane was escorted to the Tower, messengers went into the streets proclaiming her as queen to an indifferent public. At the same time, priests also took to the street delivering sermons denouncing Mary’s claim to the throne, focusing on her illegitimacy and the threat posed by her religion. The latter claimed she would destabilise the church Henry VIII had established when casting off the shackles of Rome, but happened to leave out that the nobility had gotten quite rich after absorbing church lands into their own estates, lands they would have to give back if say – a Catholic queen returned the country to papal authority.

Mary, meanwhile, was not idle. Although she had been summoned, along with her sister, to attend Edward on the 4th, a gentleman dispatched by an unknown noble intercepted her on the 6th and told her of her brother’s death and Northumberland’s intent for Jane Grey. In a moment of uncharacteristically-decisive action, Mary declared that her and a handful of her household would ride ahead to London, but instead they made for her Norfolk home in Kenninghall. The intent was no doubt to throw off any spies Northumberland had in her household while also surrounding herself with those she trusted implicitly. Had she actually gone to London, she would most certainly have been arrested by Northumberland. She immediately dispatched a rather reasonable (all things considered) letter to the Privy Council, in which she expressed her astonishment that they had failed to notify her of her brother’s condition and even worse; his death. Furthermore, she expected them to proclaim her queen, what with all that ‘rightful heir’ business she had going on.

It was on the 10th, that the Privy Council’s rather less reasonable response arrived. They denounced her claim on account of her illegitimacy, praised the virtues of Queen Jane and informed her of their own expectations that she surrender herself immediately.

During this exchange of mail, Jane was in the Tower already signing paperwork for her coronation. The Lord Treasurer, the Marquess of Winchester and one of Northumberland’s closest allies, visited her with a selection of the crown jewels, which she was happy to try on. When he offered her a crown however, she visibly recoiled, once again protesting her unworthiness to wear such a thing. The very physical symbol of her position apparently acted as a reality check for her situation and she became inconsolable, even though literally moments beforehand she had been parading the Queen’s jewels in a room full of letters signed with her royal device.

In an attempt to soothe her, Winchester told her that it would look wonderful when her husband had one made up to match. Soothe her it did not, and instead Jane hit the proverbial roof, declaring that while she might create her husband a duke as befitting his position, she would never make him king. She finished her rather heated tirade by stating that it was not within her power anyway, and that Parliament would have to consent first.

It didn’t take long for the Dudleys to get wind of Jane’s rant, assuming they hadn’t heard it themselves from the neighbouring rooms, and they came out in force against her. Guildford and his mother both demanded she relent and Jane, demonstrating that she was every bit a Tudor, refused point blank.

There are two generally-accepted theories why Jane should fire up on this point; the first being that her dislike for her husband was well known (and probably mutual), given that she had no wish to marry him in the first place and had to be (supposedly literally) beaten into submission to do so. The second is that the idea of crowning Northumberland’s son as king really hammered home Jane’s position as a pawn in his power games to advance himself and his own family. Elevating Guildford to ‘king’ would no doubt have seen Jane relegated to a figurehead position while the Dudleys ruled England through their son.

Whatever her reasoning, Jane refused to relent and the Duchess of Northumberland (after a bout of name-calling) declared that her precious son (he may just have been a teeny bit spoiled) shouldn’t have to endure the presence of such an obstinate wife. She and Guildford attempted to leave the Tower. However, Jane summoned the Earls of Arundel and Pembroke and commanded them to prevent this. While she might not have liked him, he was her husband and Jane, apparently, felt strongly that they should be seen publicly as a supportive couple. Either that or she simply enjoyed taking the Dudleys down a notch. Although they weren’t under arrest, they were expected to remain in the Tower, and sending men to ensure they did so must have given her some satisfaction considering how they had argued just a short time earlier.

Guildford however, would chair the daily council meetings that followed and entertained ambassadors, referring to himself as ‘king’.

Tuesday 11th July

Unlike the eventful Monday, Tuesday would prove to be a relatively slow news day. Jane and her supporters were making general preparations for her coronation, while Mary waited on the Council’s response to the letter she sent the previous day.

Wednesday 12th July

It’s possible that on this day the Privy Council were sitting around a table, feeling mighty pleased over the verbal smackdown they’d given Mary Tudor, and no doubt she would be giving herself up the moment she read their letter asking her to do just that. While they might not have expected her to be happy about the situation, Northumberland was quietly confident that she would have neither the military resources, nor the necessary support required to mount a solid resistance.

The slew of letters that arrived on the 12th however, were not the missives of capitulation that they might have expected. They were, in fact, news that many influential families had come out in support of Mary, including, most notably, the Earls of Bath and Sussex. Worse still was the news that they were not just publicly declaring their support, but actually marching their forces to join her at Norfolk. We can presume this to be the very moment when the Privy Council realised that they may have made a slight miscalculation in the vehemence of their support of Jane.

Northumberland now had the unexpected task of mustering an army at no notice, having considerably underestimated Mary’s defence. There were numerous reasons why Mary was able to garner so much support, not all of which were anything to do with her. While Northumberland might have thought that the nobles had preferred their increased wealth under Protestant measures he had not counted on the number of people who had never truly converted from Catholicism. Further there was Mary’s undeniably stronger claim added to that that there were many who simply just did not want to see Northumberland as de facto king. If he had managed to arrest Mary all of these points would not have mattered, but seeing as he failed and Mary was able to establish a base from which to resist, he now faced opposition he had genuinely not expected to encounter. Initially, Jane’s father, the Duke of Suffolk was placed in command of the army (Suffolk’s loyalty was understandably not in question) but upon hearing this news, Jane became hysterical and commanded that her father remain in the Tower with her.

The Council was now in the unenviable position of having already pledged support to Northumberland, going so far as to tell Mary herself that they were fully behind Queen Jane, but completely aware that Jane’s days on the throne were numbered if Mary continued to attract such significant support. When Jane declared that her father should not command the army, members of the Council jumped on the opportunity, suggesting (very loudly and very publicly) that Northumberland himself should lead the army, what with his amazing leadership qualities and military experience. As it happened Northumberland was known for a capable military commander yet as an astute politician, he would have surely grasped the implications of the Council’s offer. If he accepted, he would save face, but the moment he left the capital the Council would no doubt extend overtures to Mary. To refuse would risk his personal reputation and require him to place someone else in charge of his forces, someone who might well defect anyway. As more of the Council joined in the chorus of, “go on Northumberland you should totally do it,” Northumberland accepted.

Thursday 13th July

The Privy Council summoned their forces, though their support came together far slower than they might have expected. Some had already declared for Mary, some were no doubt playing a waiting game and refusing to commit to either side, while some would simply have been caught off guard at having to muster their forces with no prior warning or notice.

Northumberland mapped out his campaign and informed the Council, confirming that they would arrange for reinforcements (made up of those who struggled with the immediacy of the situation and couldn’t quite remember where they left their good sword) to join him at Newmarket. He dispatched a cousin to France to barter away Calais and Ireland in exchange for military aid, assuming that France would want Ireland over a Spanish Princess. Or would want Ireland at all.

Before visiting the Tower to take his leave of the Queen, Northumberland made an impassioned speech to the councillors, stressing that they had sworn loyalty to the cause of Queen Jane and reminding them that he expected them to remain steadfast in supporting him. His speech and their oaths did indeed have some effect on the councillors, who remained tacitly loyal for a further three days, before they sold him out entirely.

Friday 14th July

Northumberland marched from London to Cambridge with 1,500 men at his disposal and a smattering of artillery. Meanwhile, Mary departed from Kenninghall in Norfolk, heading for the easily fortified Framlingham in Suffolk. Mary garnered more and more support with every passing hour. Despite this, she had the foresight to request military aid from Spain (who were far, far more likely to agree without the necessity of promising a part of the kingdom).

Saturday 15th July

Disaster strikes for Northumberland. He was still marching North to Cambridge, but by now towns and even entire counties were openly declaring for Mary. Nobles had mustered their troops, but bypassed Northumberland, heading instead for Framlingham while Northumberland’s own troops began to desert. Nobles who were actually loyal to Northumberland meanwhile struggled to gather their forces, as the common man largely objected to Jane’s accession. The crippling nail in an already pretty solid coffin came when the naval ships along the Suffolk coast, placed there by Northumberland to prevent Mary’s potential escape to the continent, declared for the princess and committed their not-inconsiderable military support and artillery to her cause. When Northumberland arrived in Newmarket, the reinforcements the council had promised were noticeably absent.

Sunday 16th July

Most of the day’s action took place in the Tower, presumably because Northumberland was sitting with his head in his hands, wondering what the hell he was going to do next, while Mary accepted more troops and shouted, “come at me, bro,” from the parapets.

In London, the Council (and probably Jane herself) had been keeping themselves abreast of the news of their campaign. News that it was not going as successfully as they might have liked prompted a few defections within the household. Most notably, the Lord Treasurer absconded with a selection of the crown jewels, while the Treasurer of the Mint, Keeper of the Privy Purse also took off with the signs of his office (specifically the Privy Purse itself) and made for Mary’s camp.

In response to this, Jane ordered the gates of the Tower closed and had the keys delivered to her personally, in the hopes of preventing further defections.

Monday 17th July

By now, it was obvious to all that Northumberland’s forces could not win in the face of both Mary’s overwhelming support and the general consensus that Mary was the rightful Queen.

Tuesday 18th July

A dozen members of the Privy Council (including five Earls) all excuse themselves, under the pretence of visiting the French ambassador. An emergency meeting was held in secret wherein the above members met with the Spanish representatives (the meeting with the French ambassador a lie? Gasp!) and declared the expected excuses of: “Northumberland made us do it!”, “We never wanted Jane anyway!”, “Mary is the true Queen”, etc.

While we might expect the Spanish to have advised Mary to kick the Privy Council into touch and have them all arrested for treason, the truth of the matter was that she simply could not imprison the country’s government. She needed them, however unpalatable that might have been, and had to work with them. She would have to accept their claims that Northumberland was the only one among them who had truly not wanted the Catholic Queen restored. To this end, they drew up a proclamation against Northumberland, authorising his arrest and offering substantial rewards to the man who managed it.

Meanwhile Northumberland’s son, Robert Dudley, who had been dispatched to Norfolk with three hundred men to secure the area for Jane, successfully ended his campaign by securing the town of King’s Lynn, where Jane was proclaimed in the market place.

Friday 19th July – Jane’s reign ends here

The Privy Council publicly confirmed the results of their meeting the day before, and declared Mary Queen to a jubilant public. The men of King’s Lynn seized Robert Dudley, who must have had one of the shortest-lived victories ever, and sent him to Mary herself, where he was arrested and attainted. The Duke of Suffolk and his (now disarmed) men left the Tower of London. Jane’s reign officially ended and she was left, quite abandoned, in the Tower.

The days that followed.

Jane’s family and supporters, predictably, fell away from her almost immediately. She herself remained in the Tower (with nowhere to go) knowing that she would most certainly be arrested. Her father declared for Queen Mary nearby, on Tower Hill, and although returned home, he was arrested soon after. Jane’s mother may have left her daughter behind, but she rode for Mary’s camp and secured an audience with her. Surprising everyone, Mary promised Frances that her family was safe and the Duke of Suffolk was immediately released after just a few days of arrest. Jane, however, remained in the Tower, eventually moved out of the royal apartments and into a more suitable suite for a prisoner. Her husband, along with numerous members of the Dudley family were also imprisoned there.

Northumberland was still in Cambridge (awaiting reinforcements) when a letter from the Council arrived for him. In it, they informed him that they had proclaimed Mary as Queen, and that he was to surrender his army and await arrest. Northumberland went to the market place, where he also declared for Queen Mary, claiming that everything that he had done until now had been under the Council’s orders, and that he was sure they had good reasons for their sudden change. The following day he was arrested and taken to London, though nearly didn’t make it, given how unpopular with the public he now found himself. The French ambassador wrote that he was in disbelief at how quickly and severely men had turned against Northumberland, claiming that such changes must have come from God, as he had never seen anything like it.

On the 3rd of August, Mary rode into London followed by a train of nobles and Elizabeth (who had very suddenly recovered from the illness that had prevented her from participating in previous events), to a positively ecstatic public.

A couple of weeks later Northumberland’s trial began, where his defence consisted of pointing out how he had acted with the complete agreement of the Privy Council. Indeed, as he was but a member of the Council he could not command them to do anything, and it was they who commanded him. At one point, he drew attention to how most of the jury was as guilty in the coup as he was. Everyone involved was well aware of the situation, and Northumberland would surely have known beyond doubt that he would be found guilty, and so he begged mercy to be extended to his family. He was to be beheaded on the 21st August.

The 21st, however, came and went without an execution. Northumberland, the Lord Protector of Edward VI, the Protestant prince, the man who had pushed through numerous Protestant reforms and who had successfully placed a Protestant Queen on the throne (albeit briefly) now declared that he had seen the error of his ways and that he was a good Catholic. His execution was delayed for a day while he converted. Just as he had been the most obvious and convenient scapegoat for the coup, so his sudden “conversion” was too good a propaganda piece for the new Catholic regime to pass up. A pamphlet of his conversion and his own words denouncing the Protestant reforms were distributed (even abroad), demonstrating how right it was that the country return to papal rule.

His conversion was not enough to save him, naturally, and he was executed the following morning after a brief speech where he once again pointed out that he had only done what the Council had agreed to. Not that he’d name names, as he was totally the bigger man, but the Council (you know who you are) were the true villains.

Jane had (of course) written to Mary apologising for her part in events, claiming that she had no intention of ever coming between her and the throne and begging forgiveness. Forgiveness which Mary had already declared she would freely offer. Jane and Guildford still had to be tried, an event which occurred in November, and though they were found guilty (Jane’s letters, signed Jane the Quene, were considered somewhat incriminating) and sentenced to death there was no immediate danger that Mary would follow through with it. Jane and the Dudley sons were all returned to the Tower, ostensibly to await the Queen’s pleasure.

In December, Jane and the Dudleys were allowed some greater freedoms. They could wander the gardens with greater ease and Jane and Guildford were allowed to spend more time together. Whether either of them actually enjoyed this is another matter. They would probably have been pardoned and released eventually, but in the following January, the famous Wyatt rebellion broke out. While Wyatt’s concerns had nothing to do with Jane and everything to do with Mary’s choice of husband (who was a little too much on the Spanish side for the English public), the Duke of Suffolk did not help matters by joining the rebellion. And to compound the issue he declared for Queen Jane, thus sealing his daughter’s fate. The Privy Council, in a reactionary move, declared that Mary had no choice but to execute Jane and Guildford, in case future rebellions attempted to restore her. Mary reluctantly had no choice but to acquiesce.

Jane and Guildford were supposed to be executed on the 9th February 1554. However, this was delayed when Mary had the idea of converting Jane to Catholicism. Jane’s faith however was not as flexible as Northumberland’s and not only did she not relent, she argued her case so succinctly with Mary’s personal chaplain that the two formed an immediate friendship. So much so that he accompanied her to the scaffold when the time inevitably came.

The night before the execution, Guildford asked if he could meet with his wife one last time. Her response of ‘let’s not eh?’ can be read in one of two ways: she was either sincere in her claims that it would be too upsetting and difficult, so why not leave it until they were dead and had each other for eternity? If, however, she still harboured disdain for him, then it’s entirely possible she had little desire to spend the last night of her life in his company, eternity together notwithstanding.

That said, Guildford was executed first, and when his body was returned to the Tower, Jane apparently bemoaned his fate, crying out, “Oh Guildford! Guildford!” Jane herself was taken to the scaffold and after reciting some appropriate verses (in English, naturally), she was blindfolded and told to kneel. After some confusion over where she was supposed to go (after all, she couldn’t see anything), she was dispatched at the age of sixteen/possibly seventeen. Her body was taken to the Chapel of St Peter Ad Vincula to be lain with her husband and those beheaded Queens of old – Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard. While Jane’s father was executed ten days later, Guildford would be the only Dudley son to be executed. The remaining Dudleys were later released, after their mother and brother-in-law successfully lobbied the Spanish king for their freedom. Freedom proved to be too much for the eldest son, John Dudley, who died at his brother-in-law’s home the day after their release.

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey – Paul Delaroche – 1833 (All picture credits: Wikipedia)