My little one has been sick this week, which has seen me sat underneath her, getting sucked into the YouTube rabbit hole to avoid watching Thomas the Tank Engine on repeat. Endless repeat.

I ended up watching quite a lot of videos about creepy things that had happened in history, but unfortunately, later discovered that most of the events were proved to be unsubstantiated or hoaxes. So here goes a new series: Creepy History. A look at specific instances of creepy stuff happening, that forms the basis of the mass of creepy urban legends we have today, starting with Ghost Ships.

For as long as we’ve had ships, we’ve had ghost ships. They tend to vary in degrees of creepiness; from ships seen in the distance, never to be seen again, to ships crewed by the damned, luring sailors to the gates of hell. In reality, “ghost” ships are, more often than not, ships abandoned at sea for mundane reasons and left to drift. Any ship found without crew is considered to be a “ghost” ship, and are a surprisingly frequent occurrence. Usually, they can be traced back to their owners, reasons are given for their abandonment and they are either returned or scuttled. The most recent example of a ship designated a “ghost ship” is the Cuki, found ashore on Melbourne Beach. With only a velvet rose and a mannequin holding an enigmatic sign (“beatings will continue until morale improves”), speculation was rife as to the ships mysterious origins. The rather uninspiring truth was that the ship was caught in the strong winds of Hurricane Irma and blown hundreds of miles from its port, which while impressive given the distance it had travelled, is hardly the stuff of nightmare fuel. Such stories are common among ghost ships, but that is not to say that there aren’t documented ghost ships that transcend the mundane and enter the realms of the creepy or at least, mysterious. Such tales are not, as you might expect, limited to a time before radio communication or even (if you can believe such a thing) a time before Facebook. Lunatic Piran, the boat of veteran sailor Jure Sterk, was found in 2009 with no sign of its only occupant aboard, but with no indication of why he would have abandoned ship. Sterk is now presumed lost at sea and his unexplained disappearance proof that the sea can continue to mystify us, even in such an age of interconnectivity.

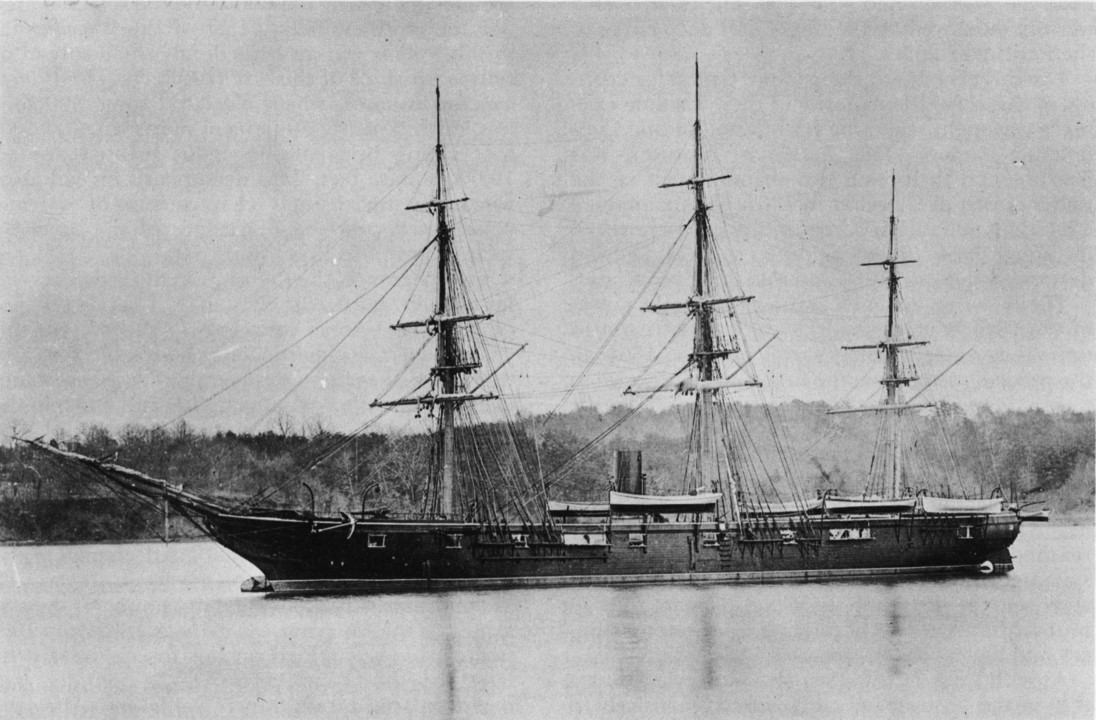

Sea Bird

One of the earlier ghost ships, the story of Sea Bird would see much embellishing, and many elements of its tale would be used in later stories of different ghost ships.

The brig was on its way into Newport, Rhode Island, around 1750 when those on the beach noticed that it was approaching under far too much sail, and looked to crash on the shoals. Crash it did not, and the gathered crowd watched the ship drift around the rocks until it came to a calm stop near the beach.

Aboard there was coffee still boiling, breakfast laid out, and the ship’s cat and dog were waiting to greet the search party. Of the crew, however, there was no sign. The ship was in fine condition, with no sign of any damage or foul play, though the ship’s longboat was missing. The most recent entry in the captain’s logbook stated that they had sighted a landmark just a few hours before the ship had drifted ashore, and later fishermen would say they saw the crew on deck around the time the captain made his entry in the log. But the longboat never reappeared and neither did the crew.

The most likely explanation was that the helmsman panicked after realising how quickly they were approaching the shoals, and the crew evacuated in the longboat, but it remains a mystery how they managed to do so, so close to the shore, in an area with heavy fishing traffic, in fair weather and daylight, and yet disappear completely, while nobody on shore sighted the boat leaving.

Sea Bird was sold, renamed and the remainder of its sea life was spent making far less unremarkable voyages. Though the legend says that shortly after the ship came ashore, it would go out to sea again in search of its lost crew, and would disappear just as they had.

Mary Celeste

In 1884, a piece written in the first person, titled ‘J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement‘ appeared in The Cornhill magazine, a reputable literary journal. ‘J. Habakuk Jephson’s‘ statement was allegedly the testimony of the only survivor of the “Marie Celeste”, a ship sailing from Boston to Lisbon in 1873. The story was reported as fact by some American newspapers, and it became incredibly popular, far more popular than the actual story of the Mary Celeste, a ship sailing from New York to Genoa in 1872. The story was published anonymously by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who did not expect it to be taken as seriously as it was. However, because the story reached a far wider audience than that of the actual ship, we have Doyle to thank for the Mary Celeste being the archetypal ghost ship.

Of the real Mary Celeste, we know a fair bit, given that there was an official inquiry in order to determine salvage rights. The Mary Celeste left New York in November 1872, heading for Genoa, carrying a cargo of methylated spirits (denatured alcohol). As well as the small crew, the Captain’s wife and daughter were also aboard, none of whom would be seen again after they departed New York. Over a month later, in early December, the Dei Gratia, a similar trade ship that left New York shortly after the Mary Celeste, discovered the latter. While some newspapers of the time reported that the search team discovered the galley fire lit, food still steaming and a log entry a mere hour before the Dei Gratia arrived, they actually found an abandoned ship with all evidence pointing to the occupants escaping in the only lifeboat. The issue was less a question of how, but of why?

There were no signs of any violence, and the ship was largely undamaged, save for the knocks it took from drifting. The captain’s log gave no indication as to why they would need to abandon ship, with the last entry marking their position almost four hundred miles away, some nine days before it was discovered. The captain of the Mary Celeste, Benjamin Briggs, was well known for his competency, and as the only indication that there was anything wrong with the ship was some flooding of the ship’s hold (which had had little impact) there was nothing to suggest why he should have abandoned ship.

An inquiry at Gibraltar focused on the notion of foul play, suggesting the crew broke into the ship’s cargo and killed the captain, and his family, in a drunken rage. However, there were no signs of a scuffle, the cargo was undrinkable, and any marks aboard used to corroborate the theory were found to be natural damage from drifting at sea. Other theories suggest that the captain acted out of mistaken judgement, feeling the ship was about to run aground, that the cargo posed a danger to them, or that the ship was taking on water at an alarming rate, he had the crew evacuate, only to be lost in bad weather as a result. Natural disasters, piracy, insurance fraud/conspiracy have all been suggested to explain the disappearance of the crew, but it is unlikely the truth will ever be known.

Zebrina

Built in England in 1873, Zebrina was found run aground in Cherbourg in 1917. Having departed Falmouth for Saint-Brieuc, France with a shipment of coal, the journey should have been a simple one, and one the ship had completed numerous times before. The circumstances of it being found off course at Cherbourg, with no crew or any indication of where they might have gone, baffled authorities then as it continues to baffle now.

Despite some minor damage caused by the impact of running aground, Zebrina was found to be in good condition, with all her emergency gear and lifeboats still aboard. The ship’s log was found in its proper place with, again, nothing to suggest what might have happened to the crew.

The prevailing theory is that the ship was attacked by a U-boat (it was 1914 after all) and that the crew was taken off onto the enemy craft before it was to be destroyed. Zebrina was of course, not destroyed, or had taken any kind of torpedo damage, nor had the enemy commander taken control of the ship’s papers, and so it was further suggested that the U-boat had bidden a hasty retreat, leaving Zebrina adrift, upon sighting an allied vessel. If this were true, and the crew had been too caught up in their situation to record even a sighting of an enemy U-boat, it still begs the question of what happened to the crew. It was assumed that the U-boat was sunk itself, with Zebrina’s crew aboard, by a British Navy patrol. That said, post-war research failed to turn up a likely candidate for which U-boat might have encountered Zebrina, nor one that might have been sunk by the Allies with its crew present.

Other theories suggest that the crew abandoned ship believing themselves to be under imminent attack, though how they escaped given that all of the lifeboats remained is anyone’s guess. Alternatively, a strong wave washed the five crew overboard, which is also unlikely given how undamaged the deck and rigging was, upon its discovery.

Another theory suggests that Zebrina was actually a heavily armed Q-ship, a ship designed to look helpless to lure U-boat’s in before they opened fire and destroyed them. If this were true, the crew would have numbered in the twenties rather than the five recorded, but the ship’s cargo was removed at Cherbourg, and there is nothing to suggest that this was anything more than the Swansea coal it set out with.

Carroll A. Deering featuring SS Hewitt

Carroll A. Deering‘s last voyage was eventful, to say the least, even before it was discovered aground with its crew missing. In late August 1921, Deering departed Virginia for Brazil, carrying a cargo of coal. At Delaware, the Captain and his first mate, (who was also his son), were let off, when the former fell ill. The two were replaced with Captain W. B Wormell and Charles B. McLellan, and the ship once more set sail in early September. It made a successful delivery and Wormell allowed the crew to go ashore, something he himself did, during which time he complained to a friend about the crew’s behaviour, with the exception of the engineer. They set sail two months later, stopping at Barbados, where McLellan followed his captain’s example and complained of both captain and crew to friends. Unlike the captain, however, McLellan proceeded to get riotously drunk and was arrested for such, when he started shouting about how he was going to kill the captain. Captain Wormell, apparently not one to bear a grudge, had him bailed and they set sail once more.

Deering was sighted twenty days later, by a lightship which recorded the encounter. The keeper spoke with a man described as having a foreign accent, (Deering‘s crew was largely Scandinavian) and was told that they’d been caught in a storm and lost their anchors. He asked if the keeper could report this to Deering‘s company, which he would have done, had his radio not been broken. The keeper took note that it was a member of the common crew with whom he spoke, rather than the captain or the first mate, and also that the remaining crewmen were visible in an area of the ship they normally wouldn’t have occupied.

Shortly after Deering had passed, the keeper sighted an unidentified steamer (thought to be the SS Hewitt, which was following a similar course to the Deering), which proceeded past him, despite his signals.

Deering was found, a few days later, run aground on Diamond Shoals, while the SS Hewitt would vanish completely. Onboard Deering, there was no sign of the crew or the lifeboats. If the crew had evacuated in this way, they had taken all of their personal belongings, papers (including the ship’s log) and the navigational equipment, leaving the ship quite empty, though there was evidence that the following day’s meal was being prepared when the crew had departed.

The investigation into the disappearance of the crew was exhaustive and included a number of other ships that were unaccounted for along the same path, SS Hewitt among them. While the majority were deemed to have been sunk by hurricanes and storms, Deering and Hewitt had both been seen to clear the bad weather. Theories of the crew’s disappearance ranged from piracy and smuggling (including specifically Russian communist pirates) to simply perishing in the lifeboats, after the ship ran aground. The known disagreements between captain and crew, and the notes made by the lightship keeper suggested that there had been a potential mutiny, wherein the crew had killed the captain. Certainly, the only remaining papers – a nautical map, showed that the captain had marked their location until the 23rd of January, at which point a different hand took over. The theory suggested that the crew then abandoned ship and assumed new identities, but there was no evidence aboard to suggest a fight or murder had taken place.

The enquiry was closed in 1921 having failed to reach a conclusion regarding Deering, and Hewitt, the same year Deering was scuttled to prevent it posing a danger to other ships.

MV Joyita

With far more claim to be considered “unsinkable” than a certain other ship in history, this did not stop the crew of the Joyita meeting with assumed disaster. A luxury yacht turned merchant vessel, Joyita left Samoa with sixteen crew, nine passengers and some not particularly valuable cargo in October 1955. Only one of the ship’s two engines were working and it was the last anyone would ever see or hear of those aboard.

Heading for the Tokelau Islands, where it would unload its cargo and passengers, and take on new cargo for the return, the alarm was raised three days after Joyita failed to appear after a journey that should only have taken two. No distress signal had been received in the vicinity and a search and rescue mission failed to turn up any sign of the ship, despite covering an area of almost a hundred thousand square miles. Joyita was sighted, over six hundred miles from her route, five weeks later by another merchant ship, listing so much that she was partially submerged, though not sinking.

The ship was taken to Suva, Fiji, where no explanation could be found for the disappearance of those aboard, and the remaining evidence succeeded in raising more questions than it answered. The radio at least was found to be transmitting on the international distress channel, but it was soon found that this had been futile, given that the radio’s cable was damaged, so it didn’t have the range to reach anyone who might have helped. There was damage to the ship, and the crew had thrown up a makeshift awning near the bridge, possibly to provide shelter. Much of the cargo was missing, as were the navigational instruments, the ship’s log and it’s firearms, not to mention all four of Joyita‘s lifeboats. One of the passengers had been a doctor, and his bag was found on deck, containing his instruments as well as bloodied bandages.

Evidence aboard pointed to the ship losing power at night, less than fifty miles from its destination. Joyita had apparently begun taking on water but was in such a poor state of repair (see also: broken radio) that the pumps were unable to combat the flooding.

Despite the condition of the ship, investigators were still at a loss to suggest what had happened to those aboard Joyita. Although the ship had been taking on water, the ship was (here’s that word again) as unsinkable as a ship could hope to be, something which the captain (and assumedly the first mate, if not the crew) would have known. Therefore, despite the flooding occurring below decks, it would have still have been a safer option to remain aboard and wait for the help that would inevitably have come when Joyita failed to make port. While enquiries found the captain to have been negligent in his upkeep of the ship and its equipment, and guilty of carrying passengers with the wrong license, his fate and that of the crew and passengers has never been determined.

As the ship’s clocks, which were all tied to its generator, had stopped at 22:25, the most likely theory was that the crew and/or its passengers began to panic at the prospect of rising water and a long, dark night ahead of them. The captain would have known that their chances of survival rested on staying aboard their extremely buoyant ship, and so there have been some suggestions that he was incapacitated or injured (possibly by the crew or the passengers), which explained the bloodied bandages, or that he’d been forced off at gunpoint, when panic had taken firm hold. A friend of the captain’s suggested that the tensions between the captain and his first mate had erupted and the two had scuffled, possibly falling overboard, before Joyita began taking on water. It is assumed that the crew and passengers were lost in the lifeboats, or that they had tried and failed, to make for some nearby land. The missing cargo would then have been taken off by another vessel, who left the abandoned Joyita in the state they had found her in.

Another theory is that the ship was deliberately stripped of its heavier cargo and passengers while the crew attempted to keep Joyita afloat enough to repair one of the engines. They failed in their endeavour and those aboard met different fates; some succumbing to injury, exposure, illness etc, others drowning and some possibly lost when tempers became too frayed.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.