If you live outside the United Kingdom (or within it – in a bubble roughly the shape of West Glamorgan) you may have escaped the extreme weather that has battered Great Britain recently. Described as, ‘Britain’s Big Chill,’ ‘Britain’s Big Freeze’ and by those within the aforementioned bubble as, ‘what snow?’ it has been described as the coldest winter Britain has experienced for twenty-five years. Particularly impressive given that it’s spring.

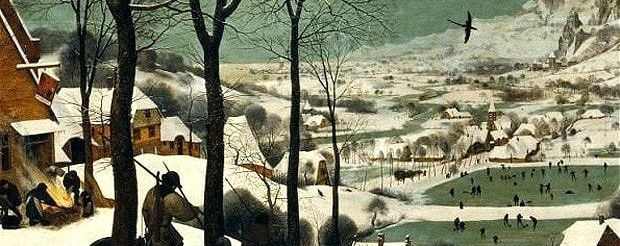

Contemporary chroniclers described the winter of 1407-8 as the coldest in living memory. Granted, that only covered a span of around thirty years, but it was still noted as particularly cold during a period that saw fifteen of the hardest winters recorded in history. ‘The Great Frost and Ice’, as it came to be called by some writers, was considered the harshest of these fifteen winters which may have occurred during a period known as ‘the little ice age.’ (Historians and climatologists disagree on dating this period).

The temperature began to drop after Saint Martin’s day (11th November) and affected much of Western Europe, with a second cold front following in December. On the whole, there was little in the way of snow. Instead, Europeans had to contend with extremely low temperatures and large-scale frost cover in what was described as an otherwise dry winter. The frost would last until February in most places, while the temperatures did not begin to rise until March.

In Maastricht rebel militia laid siege to the city, beginning their campaign in late November. They managed to ride out the cold that came the following month but in early January the harsh temperatures and heavy snowfall forced them to abandon their efforts. Unable to retreat over ground they instead turned to the river Meuse which had frozen and was usable as a crossing.

Along with the Meuse, Christmas 1407 saw a number of lakes and rivers freeze over, with many of them being used as roadways when the roads became impassable for snow or frost damage. While the freezing of such rivers as the Thames or the Seine was uncommon, it was an event that locals may have seen if not in their lifetimes, then that of their parents. For bodies such as Lake Constance, Lake Zurich, the Rhine, the Seine and the Sambre seeing them freeze over was a far rarer occurrence. Between Norway and Denmark, the North Sea was also crossable which saw a number of travellers make the journey across the sea on horseback.

The temperature seems to have risen in Britain before it did the rest of Europe. In mid-February 1408 while the frost still blanketed much of the Western continent, England saw The Battle of Bramham Moor between the forces of Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland and King Henry IV. The fact that they were able to engage in a battle and that no mention was made of any harsh conditions suggests that the worst of the winter had passed for them. Meanwhile, the rest of Europe was evaluating the cost. Trade had been massively disrupted by the frozen waterways, the disruption which continued after the weather became milder. Previously frozen rivers were now congested with ice which caused considerable flooding, damaging any nearby farmlands. Crops had frozen, livestock had died and the population of birds had decreased dramatically. In Britain, many trees across the country had burst open when the sap inside them froze and expanded.

We cannot gauge the exact temperatures of the time but if we consider the extent to which the rivers and lakes of Europe froze, the damage caused by the low temperatures and the decimation of the avian population, we can speculate that at it’s coldest the temperatures would have dropped below -25 degrees Celsius (-18 degrees Fahrenheit).

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.