I decided to do a sort of concise overview of the various deaths that affected the Tudor dynasty. Even though they were the ruling monarchs, the causes of their deaths is often unknown and limited by sixteenth century knowledge of medicine. Most of them died of an illness, or quietly in their sleep, at odds with the drama with which they are remembered. In writing this, I decided to omit the six wives of Henry VIII, as their deaths are so well documented, we still have a rhyme to remember them by.

Edmund Tudor

d. 1456 (age 26)

Even though Edmund Tudor was the father of Henry VII, the first Tudor king, he isn’t known for his massive contributions to the dynasty. In fact, beyond bedding his twelve year old bride (a scandal given that he was twenty-five) and immediately getting her pregnant, he didn’t do much else. He was in fact dead within the year, two months before his son was born. Edmund may have been half brother to the king but the Tudor name came from his father, Owain Tudor and the Tudor claim to the throne came through his young bride, Margaret Beaufort.

The Wars of the Roses were in their infancy when Edmund, Earl of Richmond went to Wales in June 1456 to quash a rebellion by Gruffudd ap Nicolas. Although successful, Edmund was still in Wales when William Herbert took South Wales on behalf of the Yorkists. Herbert moved on, leaving Edmund imprisoned in Carmarthen castle where he was struck by the plague and died shortly afterwards. There were suspicions of murder but no evidence of foul play was discovered in the subsequent investigations.

Jasper Tudor

d. 1495 (age 64)

Edmund’s brother, Jasper, Earl of Pembroke took responsibility for his nephew and was the major support for Henry Tudor during his years in exile. Not much is known of his life under Henry VII. He was restored to the titles that had been stripped from him and married to Catherine Woodville, an aunt of Henry’s wife, Elizabeth of York. The same lack of information surrounds his death.

We don’t know specifically what Jasper Tudor died of but he was in his early sixties, a fair age for the time. He died at his castle in Thornbury on the 21st December 1495. He was buried at Keynsham Abbey though his tomb was lost with the dissolution of the monasteries.

Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales

d. 1502 (age 15)

The eldest son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, Arthur died at his seat of Ludlow Castle just four months after moving there with his new bride, Katherine of Aragon. It’s unclear what exactly he died of. The consensus used to be that he died of the sweat, a particularly aggressive form of influenza. However, there were no outbreaks of the sweat nearby at the time and Arthur suffered for a month with his illness, whereas the sweat tended to kill its victims within a day or two.

It’s also been suggested that he suffered from tuberculosis which was fairly common for the time, or just some general illness that afflicted him and Katherine. He weakened over March and died on the 2nd April. In 2002 his body was exhumed and tested to see if it could be determined what exactly his cause of death was but even modern science failed to identify his mystery illness.

Elizabeth of York

d. 1503 (age 37)

After receiving news of their son’s death, Elizabeth comforted her husband by assuring him they were still young enough to have more children. Indeed they were, Elizabeth fell pregnant within months of the tragedy. At the end of January the following year, she went into the Tower for her confinement. Only days later, and far too early, she went into labour and her eighth child, Katherine Tudor, was born.

Unfortunately, Elizabeth’s condition deteriorated quickly after the birth. Her husband summoned some of the finest doctors in the country but nothing could be done and a little over a week later, Elizabeth died of a common enough infection that affected women post-childbirth; puerperal fever. The baby, Katherine, died close to her mother.

Henry VII

d. 1509 (age 52)

Losing his wife affected Henry VII on a profound level. The two of them had been undoubtedly in love and in the immediate aftermath he fell ill and almost died himself. His mother nursed him back to health however and he lived. Six years later, however, during the season of Lent, Henry’s health began to fail again. In February 1509, the king’s court moved to his palace at Richmond. Although he was still capable of carrying out his duties, his immediate circle recognised that the king was in decline.

He prayed with increasing urgency for the forgiveness of his soul (which was par for the course when one felt the end approaching) and promised that if he should survive he would turn over a new leaf, removing his more controversial councillors at court. He managed to push through the symptoms for almost two months but by the end of April it was clear that the end was very much nigh.

Henry took to his bed where, in great pain, he struggled to breathe and eat. Even then he seemed determined to live. Even as his confessor and closest attendants gathered around him to mark his death, he hung on for another twenty-seven hours, although by now he was in great pain and couldn’t breathe without an unnerving rattling sound in his throat. At some point during these hours, he had his son brought to him where he passed some final words of advice. Finally, at eleven pm on the 21st April, Henry VII died.

His death was kept a secret for two days while the councillors around him moved quickly to secure their own interests. During this time, they continued to act as though the king were still alive. The news had to break eventually though, and having delayed until the great men of the realm could be summoned to court (or so they said as their political enemies were arrested) the death of Henry VII was announced and Henry VIII was king.

Margaret Beaufort

d. 1509 (age est. 66)

Having returned to court when she received news that her son had taken ill, Margaret Beaufort was back at court two months later for the coronation of her grandson, Henry VIII. The death of her son hadn’t seemed to hastened her own end, despite her considerable age for a woman of the time. She was in good health at the coronation and “full of joy” where she foretold great things for the new king. She also mentioned that ‘some adversity’ would follow but probably didn’t expect it to be immediate.

At the feast that followed, Margaret ate and drank with everyone else but apparently did so with too much gusto. She ate a cygnet which disagreed with her and she was taken back to the rooms where she was staying. Her decline was rapid and uncomfortable. She sent for Bishop Fisher who administered last rites. Her servant reported, rather romantically, that she passed as the bishop lifted the wafer before her.

Henry, Duke of Cornwall

d. 1511 (age 7 weeks)

Born on the 1st January 1511, Henry VIII’s first child was born and the kingdom went wild. He’s important to mention because his birth was seen as a huge boon to his father’s reign. Henry hadn’t yet been on the throne for two years, the dynasty was hardly secure. Henry married Katherine of Aragon in 1509, within a year she was pregnant, and she delivered a healthy baby boy. The baby was named Henry, created Duke of Cornwall and the celebrations were immense. They included a tournament, thanksgiving processions, street parties, military salutes, and grand feasts.

The cause of baby Henry’s death went unrecorded but given how high infant mortality was, we can assume it was a common enough complaint of the young. Henry is significant because his death had the potential to be limited to a personal tragedy to affect his parents early in their reign. However, given that Henry and Katherine didn’t go on to have a living son and the sheer upheaval the country would see as a result, his life would have changed British history drastically.

Mary, Queen of France

d. 1533 (age 37)

Henry VIII’s younger sister, Mary, had once been the Queen of France but died the wife of his best friend, Charles Brandon. The two were secretly married after the death of her first husband and lived happily together. In 1528, Mary, along with many others at court, fell ill with the sweating sickness. She lived but never fully recovered, suffering from recurring illness for the remainder of her life.

In the spring of 1533, Mary’s daughter, Frances, was married at what would be the last function Mary would attend. After the wedding, Mary returned to her home at Westhorpe where she immediately took to her bed. Within a few months the secret marriage of her brother to his lover, Anne Boleyn, was announced, and Charles Brandon was tasked with organising Anne’s coronation. Brandon managed to visit his wife once during the preparations, where he would have seen that her condition was deteriorating.

Mary died on the 25th June of an illness that was likely tuberculosis, though cancer has been offered as an alternative cause of death. Some contemporaries believed that it was the news of Henry’s marriage and Anne Boleyn’s elevation that killed her, given that the enmity between the two women was well recorded.

Margaret, Queen of Scotland

d. 1541 (age 52)

Henry’s other sister, Margaret had been Queen of Scotland through her first marriage but had gone on to marry twice more to far less advantageous gentlemen. At the time of her death she was married to Henry Stewart, Lord Methven whom she had taken as a lover and divorced her first husband to marry. Stewart proved as bad a husband as the man she divorced and in her later years, Margaret seemed determined to divorce him too. Incidentally, at the time, he was living with his own lover who he married after Margaret’s death.

Margaret suffered a stroke in October 1541. The doctors seemed optimistic that she would recover and she seems to have retained the power of speech and enough of her faculties that she agreed with their diagnosis. Within a day however it was clear that she was not as well as she might have hoped and she sent for her son, James V of Scotland. In the meantime, she told her confessors her wishes and gave a message to be passed on to her son if he didn’t make it before she passed. He didn’t, and four days after her initial stroke, Margaret died at Methven Castle. James arrived shortly afterwards and disregarded her last wishes. He claimed what property she had left to her daughter for himself but did at least provide for a lavish funeral. Twenty years after her death, rebels desecrated her tomb and burned her skeleton, leaving her ashes to be scattered around the Abbey in which she’d been buried.

Henry VIII

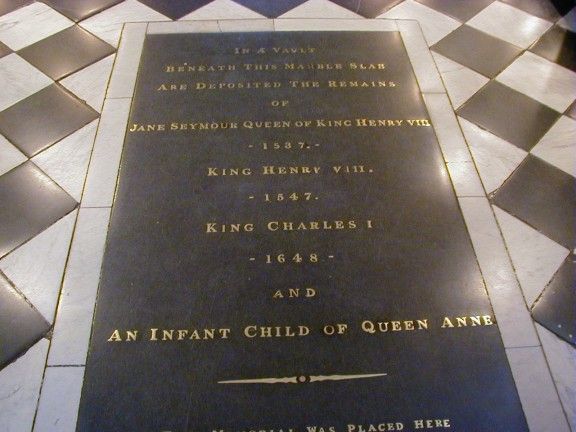

d. 1547 (age 55)

Henry VIII is arguably one of the most dramatic monarchs in British history, but his death is shrouded in a degree of mystery. In 1547, age 55, Henry VIII’s health was poor to say the least. He was obese, suffered from recurring bouts of gout, had a diet lacking many vital nutrients and vitamins, and had long suffered with a leg injury from a jousting accident that flared up and brought him to bed many times.

At the end of January 1547, Henry fell ill and it was apparent to everyone that the end approached. However, Henry had made it treason to comment on the death of the king and so nobody wanted to tell him. In the end, it fell to the groom of the stool, Sir Anthony Denny, who told the king that it didn’t look like he was going to recover. Henry asked for the Archbishop of Canterbury to come and hear his confession, but by the time he arrived, Henry was unable to speak. He did however make it known that he died in the Christian faith. There are no records to support the stories that in his last moments he cried out for Katherine of Aragon and/or Jane Seymour. Nor are there records to suggest a dog broke into the room and started lapping at the king’s blood fulfilling a macabre prophecy made during his marriage to Anne Boleyn.

We don’t know specifically what he died of but it’s accepted that whether it was scurvy, a pulmonary embolism or renal failure, it was exacerbated by his poor health and obesity. He died in the early hours of the morning on what would have been his father’s ninetieth birthday. As with his father, his death was kept a secret for two days while the surrounding courtiers moved to secure their power before the new king assumed the throne.

Edward VI

d. 1533 (age 15)

Although sometimes described as a ‘sickly child’, Edward VI’s final illness was a somewhat isolated, if not lengthy, affair. In January 1533, Edward began suffering with a cough. In the coming months, this cough would become worse until he had to take to his bed. While he had moments of rallying and being well enough to take some small exercise, on the whole he was said to be wasting away and wasn’t expected to recover. During this time, he still had the aggressive cough and doctors were concerned by the discoloration of his phlegm. His legs and head became swollen, he was attacked by a recurring fever, he couldn’t eat, and could only sleep after being administered an opiate.

On the 1st July, Edward made his last public appearance, shocking those who saw him by how thin and wasted he had become. His condition continued to deteriorate even though it couldn’t have gotten much worse. His body had almost completely failed, his nails and hair were falling out, and having willed the succession to his cousin Lady Jane Grey over his sister Mary, he was heard to wish for death.

He died on the 6th July 1533 and once again his death was kept secret so that Lady Jane Grey’s succession could be assured. Edward’s illness had struck his lungs but may not have been tuberculosis. It seems likely that it was an infection, possibly from a tumour, that started in his lungs and possibly led to septicaemia.

Mary I

d. 1558 (age 42)

Mary would suffer from debilitating and recurring illnesses from her adolescence. Her mental health suffered along with her physical health and, as an adult, she had two phantom pregnancies. Her second pregnancy was met with scepticism than her first. The swelling of her stomach was thought to be dropsy (or a build up of fluid) and eventually she was forced to concede that there was no baby.

Although she recovered from this episode, she was ill again in the following summer. She couldn’t sleep and suffered bouts of depression. Her swelling returned with a fever that left her confused and her sight diminishing. Although she had some periods of lucidity, it was clear that she was not going to recover.

This time, there would be no deathbed coup. Instead, her courtiers flocked to the house of her half-sister, Elizabeth, whom she had confirmed as her successor. Her disinterested husband, Philip of Spain, sent his representative, Count Feria back to England with a doctor, having heard of his wife’s illness. Disinterested to the end, Feria’s true mission was to make haste to Elizabeth and begin overtures as a prelude to marriage, even as Mary lay dying.

By now, Mary could not see but despite the pain of her illness, when the end came, she passed peacefully in the early hours of the morning on November 17th. As ever, the cause of death is disputed but is thought to be linked to ovarian cysts or a tumour (possibly cancerous) hence the earlier phantom pregnancies. It may also have been a virulent form of influenza that was sweeping the country at the time

Elizabeth I

d. 1603 (age 69)

The closing years of Elizabeth’s reign were marked by personal tragedy. She was, by now, an old woman and those around her were themselves succumbing to old age and infirmity. Losses were becoming more common and close together. William Cecil, her most trusted advisor, arguably the rock upon which she built her reign died in 1598. In 1601, she was forced to execute her favourite, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex for treason, which affected her deeply. The death of the Countess of Nottingham, her loyal servant for almost fifty years, seemed to be the final tragedy.

In January 1603, Elizabeth conceded that she was unwell and retired to Greenwich. There, she refused to eat, drink, or sleep, and instead would stand for hours on end with her finger in her mouth. When she was eventually forced to lie down, she refused to take to her bed claiming that she saw horrors within it. Instead, she lay on the floor of her chamber, supported by cushions. Her ladies called for doctors but Elizabeth wouldn’t see them or allow them to give her anything that was supposed to help her. She slipped into occasional bouts of delirium, hallucinating visions of friends and enemies whether they were dead or alive.

Eventually, she was carried to her bed where she declined. In her final days, she was unable to speak but could still react to the prayers being said to her, shaking her head when those praying did so for her long and continued life. On the 24th March, she passed quietly in the night. Her cause of death is unknown as she didn’t allow for a post-mortem but we can assume it was the effects of old age, exacerbated by her refusal to eat, drink and sleep which undoubtedly contributed to her fragile mental state.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.