When considering the question of Elizabeth I’s virginity, one name comes to mind immediately and before all others: Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. If Elizabeth had sex with anyone it would surely have been him. He was, after all, the great love of her life and those feelings were certainly requited. He was at her side ’til death did them part and for a long time, he was the main contender for her hand in marriage. When he wasn’t actively pursuing her for himself, he was the major obstacle between the queen and any foreign match she might make exercising an unofficial power of veto over any potential suitor. At times they argued and their quarrels are as legendary as their relationship but there’s no doubt that Elizabeth adored him and the feeling was mutual. Did this however mean that the Virgin Queen gave up her claim to virginity for him? Naturally, we can’t say anything with certainty but we can at least consider their circumstances and whether they were likely to fall into bed with each other.

Elizabeth and Dudley had known each other from childhood. They were close in age with Elizabeth born the year after him. Dudley was a part of her brother’s entourage and we know that as children they were friends, possibly even what a modern onlooker might describe as best friends. They were close enough that she confided in him at eight years old that she intended never to marry and would remain a virgin for life.

When Edward VI became king, Dudley’s father would become one of the most powerful men at court which naturally brought Dudley himself into prominent circles at a court that Elizabeth was welcome at with increasing ceremony. The two were still friends but there was no hint of anything romantic between them. Elizabeth’s name had been linked, to her detriment, with Thomas Seymour, and Dudley had found love with a gentry heiress, Amy Robsart. Dudley and Amy were married in a royal palace in the presence of the king in 1550. We don’t know if Elizabeth was a guest but she would most certainly have known about the event.

When the king died, they would both suffer under his successor, Mary. Both were imprisoned in the Tower of London for offences related to treason. That isn’t to say they could have bonded during their time there as they were kept in separate sections. Elizabeth’s stay overlapped only briefly with Dudley’s much longer sentence before she was moved to Woodstock where she would remain under house arrest for another year. Despite their separation, their closeness remained and Dudley was noted by King Philip of Spain (at the time also King of England) that he was a particular friend of Elizabeth’s.

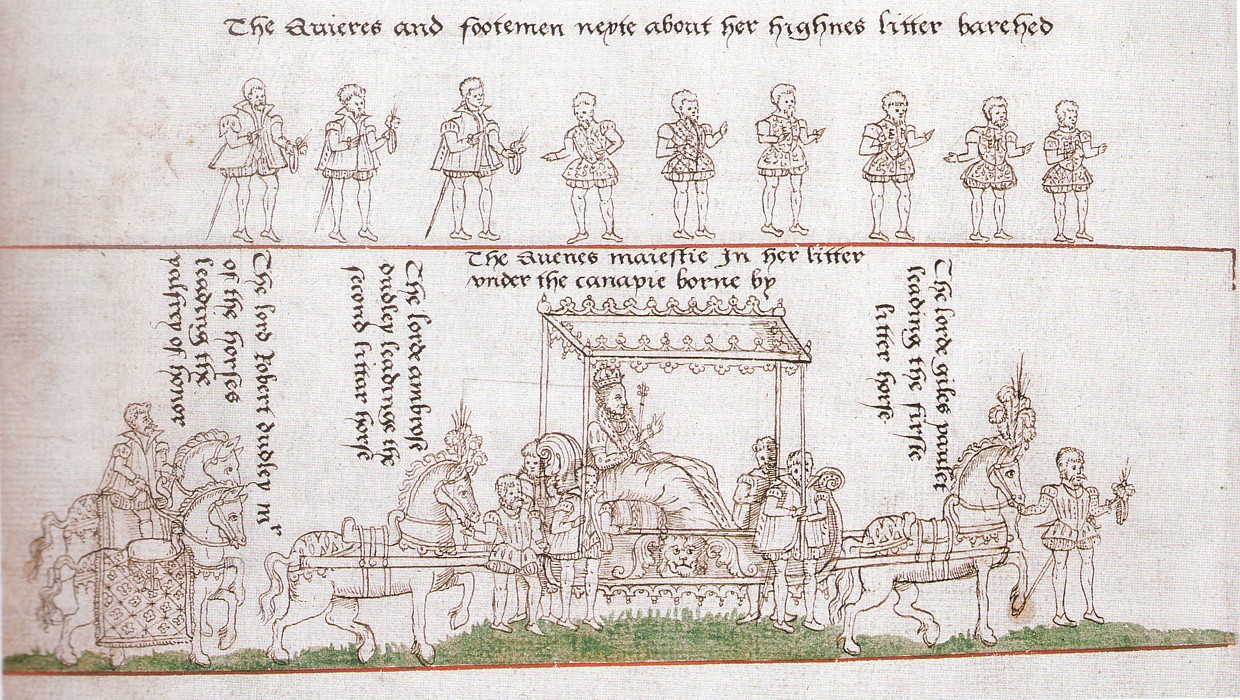

On 17th November 1558, Mary I died, Elizabeth became Queen Elizabeth I and Dudley immediately rose to prominence. The day after Mary’s death, he was present to see Elizabeth receive the Great Seal and created Master of the Horse which immediately established the favour in which he was held. In a practical sense, he was extremely well suited to the role. His jobs included ensuring the queen got to where she needed to go (and being Robert Dudley ensured she did so in style). He arranged the courtly entertainment and festivities, which included a leading role in the coronation, quite literally, and it required constant attendance at court. It took only until April 1559 for Dudley’s name to be linked with Elizabeth’s in a manner beyond that of courtly relations.

Before we start looking at Dudley and Elizabeth’s relationship it’s important to note that even though their obvious love for each other would last until his death (and indeed, for her part beyond it), the idea that they were lovers was only really widespread in the early years of her reign. Beyond 1565, Dudley’s prominence at court was an established fact and his position as favourite largely unassailable. The idea that he was actively the queen’s lover, however, was by this time confined to the occasional outlandish rumour and wasn’t believed by anyone in court circles as a certainty. For those first seven years, however, the opposite was true and their relationship was such a scandal that they became the primary subject of gossip across Europe. In general terms, if Elizabeth I had slept with anyone (and as we’re dealing with terms like virginity, we’re talking about penetrative sex with a man because historians are apparently extremely limited creatures) it was Robert Dudley and it was between the years 1559 and 1565.

So let’s consider those years.

The issue of Elizabeth’s marriage was an immediate one, as it was generally accepted that a queen couldn’t reign alone. She’d surely have to marry and share the power with a man. The question of who that man would be would dominate Elizabethan politics for the first half of her long reign. In April 1559, the Spanish ambassador, Count Feria, wrote to Philip of Spain to say that the queen and Dudley’s marriage was surely imminent and rather than press his own suit, he’d do better to ingratiate himself with Dudley.

The sentiment was shared by most of the court. Everyone had noted how favoured Dudley was beyond that of a normal favourite. Dudley had no official political power having not yet been elevated to the Privy Council but he was still thought to influence Elizabeth’s decisions. His attendance on her was almost constant and they were said to visit each other day and night in each other’s chambers. Dudley’s rooms were almost always closest to the queen’s and throughout her reign when she went on progress, he was housed in the same building as her unless it couldn’t be avoided. Everyone seemed to be holding their breath and waiting for Elizabeth and Dudley to announce their intent to marry.

There was of course the issue that Dudley was in fact already married. Amy Dudley was not in attendance at court with her husband but she was still very much alive. Incidentally, much has been made of Amy’s absence from court but it wasn’t wholly uncommon for prominent courtiers to attend the queen without their wives. The fact remained that Dudley had a living wife and unless he divorced her or she died, he wasn’t at liberty to marry. In Feria’s letter of April 1559, he mentions that Amy was sick with a ‘malady of the breast’ and likely to die soon. This is however the only instance of such a claim and there’s no other supporting evidence to suggest that Amy was ill at this point.

Dudley and Elizabeth remained so close that in November of that year, her beloved companion Kat Ashley, argued with her over his presence. She begged the queen to send Dudley away and told her that their conduct was a scandal across Europe. Elizabeth refused and argued that she and Dudley had never done anything improper and were hardly given the opportunity to given that she was accompanied by her ladies at all times, including at night while she slept. She also pointed out that if she chose to take a lover nobody would be able to deny her, which probably wasn’t the reassuring witty smackdown she thought it was. Regardless, Dudley wasn’t going anywhere.

By January of the following year, it was widely believed that Dudley would divorce his wife and marry the queen. His position at court was solidified even more when Elizabeth’s primary advisor, William Cecil, spent some time in Scotland negotiating diplomatic terms. He returned to find that Dudley was acting as all but king in name. Punishments were doled out to people caught perpetuating gossip regarding the queen and Dudley. One woman found herself in the Tower for suggesting that Elizabeth had borne Dudley’s child. Another man was subjected to minor mutilation for claiming the two had been caught in flagrante. Far from quieting the rumours, such punishments only served to enforce the idea that they were entirely true. The situation became so intolerable for some that Cecil considered resigning his post.

Courtly love was common enough among monarchs but Dudley and Elizabeth took the tradition of flirting beyond what was allowed by convention. They visited each other in their rooms without prior notice. They kissed openly on the mouth, which wasn’t unusual in England seeing as it was the courtly greeting of choice, but Dudley did so without invitation and often instigated it himself. They met in private frequently (as Elizabeth did with many of her counsellors) and she was known to slip out with her ladies to watch Dudley when he participated in sports. He was her partner in dancing, hunting, and all manner of courtly activities. During an evening on the Thames, she shared a boat with Dudley where they invited the new Spanish ambassador to marry them. In jest, of course. With him seemingly sharing the power of the crown, it was natural to assume that he was also sharing her bed.

In September 1560 the unexpected happened that threw the rumour mill into a frenzy. Amy Dudley died, leaving Dudley a widower and free to marry. The circumstances of her death could fill a book of their own so for our purposes, we’ll just consider the most basic of implications. Ostensibly, she fell down a staircase and broke her neck but rumours were rife that Dudley had killed her in order to prepare the way for marriage to the queen. An inquest cleared him and any third party of guilt but that was hardly enough to still the rumours. If they had been lovers while his wife lived then surely now would be the time for Elizabeth and Dudley to marry and make their relationship public.

The fact that they didn’t has gone a long way to supporting the idea that the queen and Dudley were not lovers after all. When encouraged to marry a foreign power, Elizabeth flattered, diverted, and dissembled. When pressed to marry Robert Dudley, she flat out refused, and at one point even offered him in marriage to her counterpart Mary, Queen of Scots. The court was baffled by this turn of events and if those who knew her couldn’t figure it out, it’s no surprise that five hundred years later we’re still in the dark as to why she made such an offer. The two were obviously very much in love and now they were relieved of the only obstacle to what could be a long and happy marriage. Instead, Elizabeth was offering her would-be husband to her cousin.

Rumours that they were lovers and that Dudley was to be king died off somewhat when quite simply, it didn’t happen. In 1562 it began circulating that Elizabeth and Dudley had in fact married in secret but there was still no sign of a coronation on the horizon. There was however the potential for a funeral. [Dramatic Music].

In the autumn of 1562, Elizabeth fell ill with smallpox and her prognosis was not good. She became delirious, slipping further and further into a fever while the tell tale red blisters of the disease appeared. It looked as though the queen would die, though she would rally briefly enough to name her successor. To the horror of everyone but the surprise of nobody, she named Robert Dudley as Lord Protector. As a decision, it was nonsense that would never have been honoured but it does show that at the moment of her death she was thinking of him and his security if she were gone. Of particular note, however, is her confession in which she affirmed that she and Dudley had done nothing improper.

Though her illness was severe, it eventually abated. The queen was left scarred but alive, and the scars weren’t so bad that they couldn’t be covered by what passed as makeup at the time. Life returned to normal at court. Elizabeth continued to evade the subject of her marriage and Dudley remained her favourite. His miniature was kept close at hand, wrapped and labelled as ‘my Lord’s portrait’. When she elevated him to the peerage in 1564 and created him Earl of Leicester, she took a moment during the ceremony to caress his neck, and he continued in his general familiarity.

In 1565 Dudley proposed marriage again but Elizabeth deferred and asked that he ask her in a few months. In true Elizabeth fashion, she then went out of her way to favour one of Dudley’s rivals to provoke him. He may have proposed again but she didn’t accept. From this point on, their relationship seems to have settled into familiar and loving affection. Dudley was still housed in the rooms beside hers, they still dined together privately, and their letters were still attentive, but the frenzied gossip that dominated the early years of the queen’s reign had died down. From this point onwards rumours that they were lovers or about to be married were few and far between. When Mary, Queen of Scots suggested in the late 1560s that Elizabeth intended to marry Dudley, it didn’t raise much of a reaction. By this time, Dudley’s wife had been dead almost ten years and they still hadn’t made any steps towards marriage.

Dudley’s name was eventually linked with other women. In 1568 he was involved with Lady Douglas Sheffield who bore him a son, also called Robert Dudley. His relationship and the resulting child hardly raised an eyebrow at court even though it wasn’t specifically hidden. His marriage in 1578 was the source of a number of arguments between himself and Elizabeth but he eventually returned to court and continued to live in the queen’s favour. He was at her side at Tillbury as they waited for news of the Spanish Armada and dined with her in the weeks that followed. His health however was poor and at the end of August 1588, he left court to take the waters at Buxton. On the 28th he wrote a letter to Elizabeth but he would never see the reply. On the 4th of September, he died en route to Buxton. Elizabeth marked the letter as ‘his last letter’ and kept it beside her for almost fifteen years before her own death in 1603.

“I most humbly beseech your Majesty to pardon your poor old servant to be thus bold in sending to know how my gracious lady doth, and what ease of her late pains she finds, being the chiefest thing in this world I do pray for, for her to have good health and long life. For my own poor case, I continue still your medicine and find that amends much better than with any other thing that hath been given me. Thus hoping to find perfect cure at the bath, with the continuance of my wonted prayer for your Majesty’s most happy preservation, I humbly kiss your foot. From your old lodging at Rycote, this Thursday morning, ready to take on my Journey, by your Majesty’s most faithful and obedient servant,

R. Leicester

PS Even as I had writ thus much, I received Your Majesty’s token by Young Tracey.”

The million-dollar question then. Elizabeth and Dudley had clearly been in love but had they been lovers? Again, I stress that we can’t know for certain one way or the other but if we consider the evidence and speculation of the time then the answer is, rather surprisingly: no.

If the queen and Dudley had engaged in a physical affair then it would have been a short-lived thing. Elizabeth was correct when she told Kat that a thousand eyes watched her day and night. She was left alone with Dudley in few and extremely rare circumstances that hardly lend themselves to longevity when conducting an affair. Further, it’s unlikely that the queen would have risked a pregnancy especially during a time when she could not marry the father, which happened to be the time that everyone considered them to be sleeping together.

Her testimony in 1562 that they hadn’t done anything improper can probably be taken at face value. We can’t underestimate the religious mores of the day. From a modern standpoint which takes a more cynical view of religion and confession, there’s a tendency to dismiss things said at times like these and chalk them up as easy lies. But Elizabeth was on her deathbed and it’s highly unlikely that she would have ended her life on a lie to protect a reputation she hadn’t seemed too bent on protecting in life.

If we therefore accept that they hadn’t been lovers before 1562, we turn our attention to the years that followed and ask if they were likely to have had sex during that time. Again, the answer is no. If they hadn’t indulged at what was considered the height of their passion then it’s unlikely they would have fallen into bed together when their relationship and indeed her reign had settled somewhat. Also, if they were interested in pursuing a physical relationship then they could have just gotten married and saved themselves the hassle of sneaking around. By this point, even parliament had accepted Dudley if it meant getting the queen down the aisle but she was resolute.

Ultimately, our greatest proof that Elizabeth was committed to the course of virginity is in that she didn’t marry, not even when she had the chance of marrying the man everyone supposed was her lover. We know there was no secret marriage as rumoured or Dudley wouldn’t have married elsewhere. The same can be said of an affair. If Dudley were enjoying the queen’s physical affections then he probably wouldn’t have gone involving himself with other women. As a not altogether unrelated aside, if the two of them had been having sex at the start of her reign, they might have been able to restrain themselves in public and saved it for the bedroom, thus putting an end to the rumours anyway.

Personally, I believe the queen did have a sexual relationship with Dudley even if it didn’t involve the penetrative sex that the definition of virginity is so dependent on. That said, I wouldn’t exactly be surprised to learn that their relationship was entirely innocent. The question of whether Elizabeth and Dudley had sex is tied up in all sorts of gender politics and courtly conventions of the time when what is clear is that the two shared a deep and passionate love that may not have been consummated but was no less fulfilling for it.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.