For Elizabeth I, the insult that she might not be chaste lasted until the very latest years of her reign. The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 put paid to the idea that her queenship was in any way diminished by the lack of a husband, and marriage negotiations had not been seriously considered since a potential match with Francis, Duke of Anjou had fallen through. For the majority of her subjects, the virgin queen was an icon. But naturally, there were always whispers about the truth of her chastity, even after her great favourite, Robert Dudley, died. Not that rumours of her indiscretions were limited to Dudley when he was in ascendance at court. For as long as Elizabeth had favourites, her enemies were prepared to accuse her of sleeping with them.

The Minor Flings: Thomas Heneage and Christopher Hatton

Of all the names connected with Elizabeth I, Thomas Heneage is probably the one who had the least cause and opportunity to share the queen’s bed. Heneage was, at best, a minor politician from a family of minor politicians but he became a courtier from the mid-1560s. He was close to both William Cecil and Robert Dudley, so it isn’t really surprising that he would find himself in Elizabeth’s good graces. In 1565, she created him a Gentleman of the Privy Chamber. His father had occupied the same position under Elizabeth’s father, but under a queen, the makeup of the Privy Chamber was quite different to that of a king. The positions available to men were extremely limited, as most of Elizabeth’s needs were attended to by her ladies. Heneage was given a rare position allowing him access to the queen beyond the public spectacle but it wasn’t this that drew rumours of an affair.

Despite his friendship with Dudley, when Elizabeth had cause to make the great love of her life jealous, it was to Heneage that she turned. When Dudley first flirted with Lettice Knollys, then the Countess of Essex, Elizabeth responded in kind with Heneage. When Dudley proposed to Elizabeth, she told him she’d consider it, right before she spent the rest of the season flirting with Heneage. When Dudley argued with Heneage, the queen only favoured him more. The pattern is undeniable and while Heneage enjoyed a relatively successful, if not blinding, career at court, his moments as favourite were limited to when Elizabeth wanted to make Dudley jealous. There is no evidence that she extended him any particular or personal favours.

Heneage was married before he came to court so he wasn’t the most likely candidate for an affair with the queen, and despite her performances, he remained friends with Dudley. When, in 1586, Heneage was chosen by Elizabeth to attend Dudley in order to revoke certain offices that he had acquired, Heneage protested the action. It didn’t do him any good but he did at least protest it.

At the same time, another gentleman at court was rising rapidly through the ranks which naturally made him the next name for the queen’s naysayers to link with hers. Christopher Hatton first came to the queen’s attention at a ball where she noted his excellent dancing skills. Thus began an exceptional court career and a close relationship with the queen that would last until his death in 1591.

According to Sarah Gristwood, ‘a delighted Elizabeth could be forgiven for concluding that here was a man who really might die for love of her.’ Such was the adoration evident in his letters to her. His prominence at court, however, never seems to have extended to the queen’s private chambers. While Mary, Queen of Scots (who was quick to accuse her cousin of infidelity with anybody she could) claimed that the two were having an affair, the accusation didn’t set the court aflame with scandal.

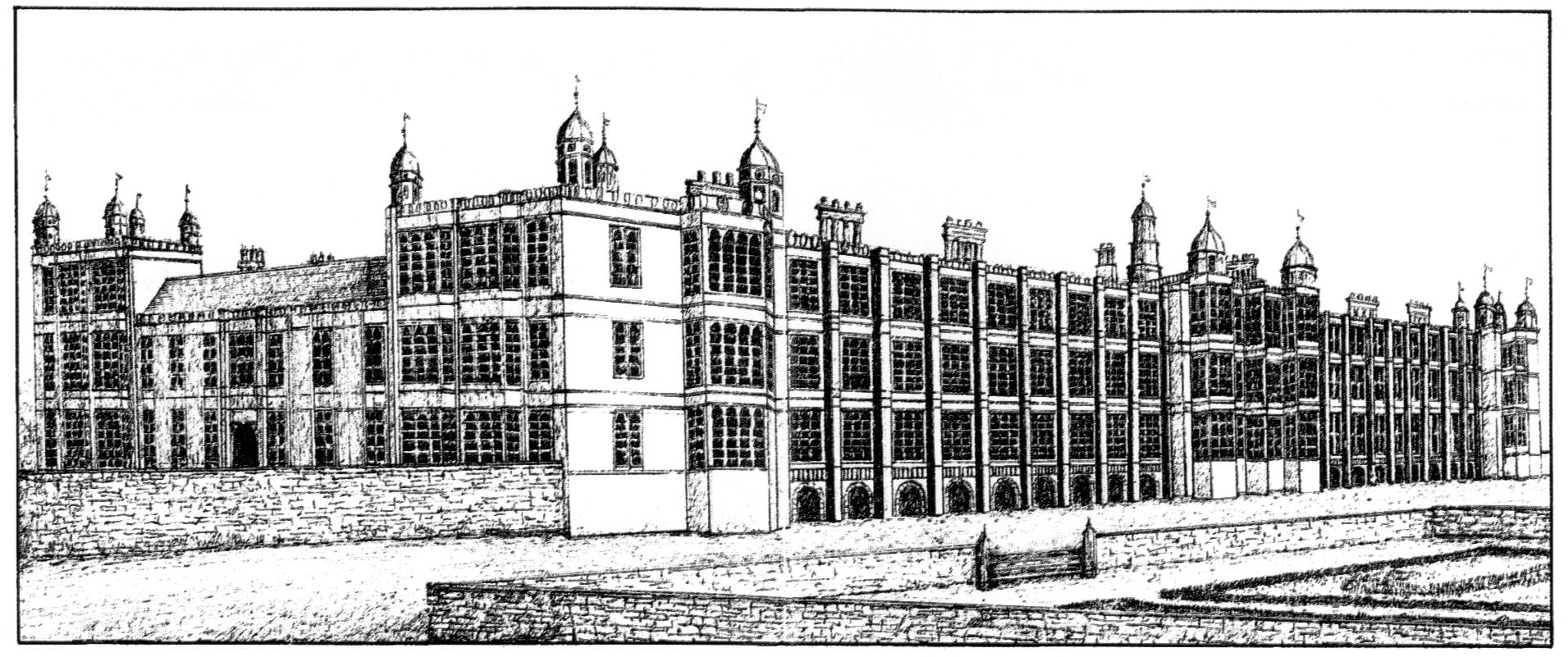

Hatton may well have been in love with the queen for his part. He never married and his letters to her were, even by the standards of courtly love, excessive in their romance. He was a constant defender of the queen and not just through the various positions that he occupied throughout his career. He led prayers for her safety and health in the House of Commons, he acted as her spokesman to Mary, Queen of Scots, and he probably spent more time at court to be near her than any of her other courtiers (save for those required for government). Later in life, his correspondence remained adoring, and he set to work building a magnificent home worthy of the queen’s presence. He practically bankrupted himself in its construction, going so far as to have an entire village moved for the sake of an improved view. When complete, Hatton vowed never to sleep a night there until the queen had. While she visited him in his final illness, at the time he was staying elsewhere and she (so subsequently he) never actually stayed at the house.

No death, no, not hell, shall ever win of me my consent so far to wrong myself again as to be absent from you one day. I lack that I live by. The more I find this lack, the further I go from you. To serve you is heaven, but to lack you is more than hell’s torment. Would God I were with you but for one hour. My wits are overwrought with thoughts. I find myself amazed. Bear with me, my most dear, sweet Lady. Passion overcometh me. I can write no more. Love me, for I love you. Live for ever.

Christopher Hatton to Elizabeth, summer 1571

Walter Raleigh

Walter Raleigh (or Ralegh, depending on how you wish to spell it) is most famous for his involvement in defeating the Spanish Armada, and for the legend which saw him laying his cloak across a puddle so that the queen wouldn’t risk getting her feet wet. His relationship with Elizabeth I is the focus of the extremely popular yet historically atrocious Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007) where she is shown to be more than a little in love with him but alas! He is headstrong and wants adventure more than he wants to remain at court.

Raleigh is unusual in that he didn’t come to Elizabeth’s attention through traditional courtly ways. He didn’t ingratiate himself with a relative or acquaintance already at court in an attempt to gain position. Instead, he excelled first as a soldier in the army and then as an explorer under warrant from her majesty before he established himself at court. That isn’t to say that he was a commoner serving as a regular soldier. He might not have been of particularly auspicious noble birth but he had familial links with the Champernownes (Kat Ashley’s family) which inevitably ensured his eventual attendance at court.

He came to Elizabeth I’s attention in the 1580s after returning from America. He was noted for being particularly handsome and after capturing the queen’s eye, he flaunted his looks in such a way that it became a compliment to her. He wore her colours, her favourite jewels, and signs of her favour, which surely only appealed to the queen’s well-documented vanity. He was given several positions at court but his most significant appointment was to the post of Captain of the Queen’s Guard. As her bodyguard, Raleigh was granted access to the queen’s private chambers and allowed to be in her presence when she wasn’t necessarily made up for the courtly spectacle. Naturally, rumours that they were lovers soon followed. Raleigh had access to the queen, opportunity, and while he made a show of his devotion to her, she was clearly enamoured with him. She insisted that he remain close to her, something which backfired somewhat when he began an affair with her lady in waiting Bess Throckmorton.

When Bess fell pregnant in 1591 they were hastily married in secret and, unusually for court intrigues, actually maintained the secret for over a year, despite the birth of a son. When it was discovered, the two were thrown into the Tower and Raleigh was temporarily relieved of his appointments. Within a year, Raleigh was back at court and a favourite of Elizabeth’s, but this isn’t the proof of their physical intimacy that many of his detractors claimed it to be. Elizabeth kept a tight leash on her ladies, and a tighter one on her gentlemen courtiers (and not in a kinky way). A surprising number of marriages were made in secret and in their aftermath, it was usually the male favourite who returned to the queen’s side while his wife remained in practical exile. Raleigh was not alone in this, and if Elizabeth slept with every man she recalled after a secret marriage, this list would be significantly longer. Even Robert Dudley suffered this fate.

Unlike Robert Dudley however, Raleigh’s time as Elizabeth’s favourite was shared with another. Enter:

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

The Earl of Essex came to court in 1584 with his stepfather, the Earl of Leicester and with his youth, good looks, and dazzling personality established himself as an immediate favourite of Elizabeth’s and an obvious replacement in her affections for Leicester when he died in 1588. He had already been appointed as Master of Horse in 1587 but unlike his stepfather, he had little aptitude for the positions he occupied. He also took the queen’s favour for granted and his behaviour towards her frequently lacked respect. On one occasion, the two argued publicly and, after she had slapped him, he drew his sword on her prompting outrage and a brief banishment.

Despite their tumultuous relationship, Essex was quickly restored to favour after their arguments. Even though he was almost thirty-five years her junior, rumours abounded that Elizabeth and Essex were lovers. He would frequently stay up all night with her in her chambers playing cards, reading poetry or playing other games. During the day, they would hunt together. He was always at her side save for the times they argued and he put so much distance between them that he would go on foreign expeditions so as to make her miss him. His intent seems to have been that in her desire to have him back at her side, the queen would forget their quarrel. For the most part, he was right. It was only as his behaviour became more inclined to insubordination, that she became less inclined to forgive him. Ultimately, insubordination and unruliness escalated into rebellion and treason. Essex was beheaded in 1601 after attempting to overthrow the queen’s government by force.

But were they lovers?

It’s been suggested that Essex was never fully aware that courtly love was a game to Elizabeth and he believed that she loved him to the point where he thought he might become king. Even considering that his rash behaviour would lead him to the executioner’s block, it’s doubtful that he ever thought he could rise that high. If he did, then it would make sense for him to become Elizabeth’s lover but despite her obvious feeling for him, and indeed Raleigh, it’s unlikely she took them to her bed.

As ever, we can’t say with certainty whether she did or didn’t but there are certain things that count against it. The most telling is that both Raleigh and Essex got married in the early years of their court ascendancy. If they were engaged in a physical, sexual relationship with the queen, then they would surely not have run the risk of angering her by marrying another, especially as the marriage alone had the potential to ruin them.

It’s far more likely that the queen, growing older as she was and having lost Leicester, was trying to recapture the earlier days of her reign when she was young herself and surrounded by young, handsome men trying to win her favour. Whether she would go as far as to invite them to her bed is doubtful at best. Assuming that she didn’t sleep with Robert Dudley, it’s unlikely she would sleep with Raleigh or Essex. Men who were considerably younger than herself and who had wives of their own. Perhaps, the most telling instance is when the Earl of Essex deserted his commission in Ireland, abandoned his army, and rode under cover of darkness to the queen’s chambers. There, he came upon her in a state of undress, which was mortifying to them both. Elizabeth placated him long enough to secure his banishment from court, at which point he began referring to her “crooked carcass” which is hardly the reaction of a lover who had already seen and enjoyed the body of the queen.

In conclusion then: was the Virgin Queen a virgin? Taking virginity as the absence of penetrative sex then yes, she probably was a virgin and not just because she vowed never to marry from eight years old. The risk of falling pregnant was immense, contraception was non-existent, and her hold on the throne far too tenuous to see through the scandal of an illegitimate child.

Did this mean that the Virgin Queen wasn’t sexually active though? Probably not. She most definitely overstepped with Thomas Seymour in her youth, though modern standards would consider her the victim of grooming. Even by the standards of the time, Seymour was going beyond the pale by courting his fourteen-year-old stepdaughter. Beyond that, she was probably involved in some way with Robert Dudley and if she could have married him without giving up the power of the crown then she likely would have. Dudley was the absolute love of her life and though she clearly loved Raleigh and Essex, they still never approached the level of intimacy she had with him. If she never went as far as sex with Dudley, then I don’t think anybody else really had much of a chance with her.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.