In June 1941 five of Queen Elizabeth II’s cousins, Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyon, and Idonea, Etheldreda, and Rosemary Fane were committed to The Royal Earlswood Institution for Mental Defectives. It had been renamed some years earlier from The Asylum for Idiots but both names give you some idea as to the colour of the place. In The Crown, the episode The Hereditary Principle deals with Princess Margaret’s discovery of her cousins and the cover-up created by the royal family and Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother. In it, the Queen Mother says;

The hereditary principle already hangs by such a precarious thread. Throw in mental illness and it’s over. The idea that one family alone has the automatic birthright to the Crown is already so hard to justify. The gene pool of that family had better have one hundred percent purity. There have been enough examples on the Windsor side alone to worry people. King George III, Prince John, your uncle. If you add the Bowes-Lyon illnesses to that the danger is it becomes untenable.

The Crown Season 4, Episode 7: The Hereditary Principle

The Crown offers the suggestion that the Bowes-Lyons family were scrutinised in a way they couldn’t have anticipated after the abdication of Edward VIII and the elevation of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyons to Queen. As a result, her nieces Nerissa and Katherine along with three of their maternal cousins were committed and false dates were given out to create the impression that they had died. But The Crown while based on real events is ultimately fictional. The Queen Mother was likely not involved in a conspiracy to hide away her nieces though she certainly knew of their existence before the press discovered it in 1987. Princess Margaret’s discovery of them is probably a fictional vehicle through which to explore the story of her cousins.

The lives of these hidden cousins present a mystery that endures today even though the youngest cousin, Katherine, died in 2014. From the moment of their discovery by the press the royal family seemed to distance themselves from the cousins and the resulting scandal. Even now, facts regarding the cousins and their situation are extremely hard to discern and the motives of the families involved; practically impossible. But we do have a rough timeline of events and that allows us to engage in that most wonderful of pastimes: speculation!

From Glamis Castle to the Royal Earlswood Institution for Mental Defectives

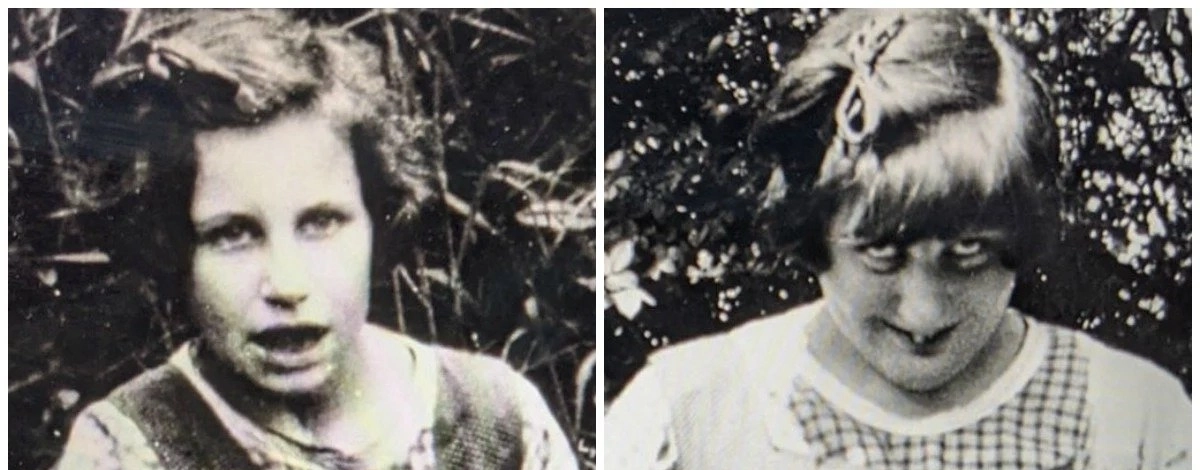

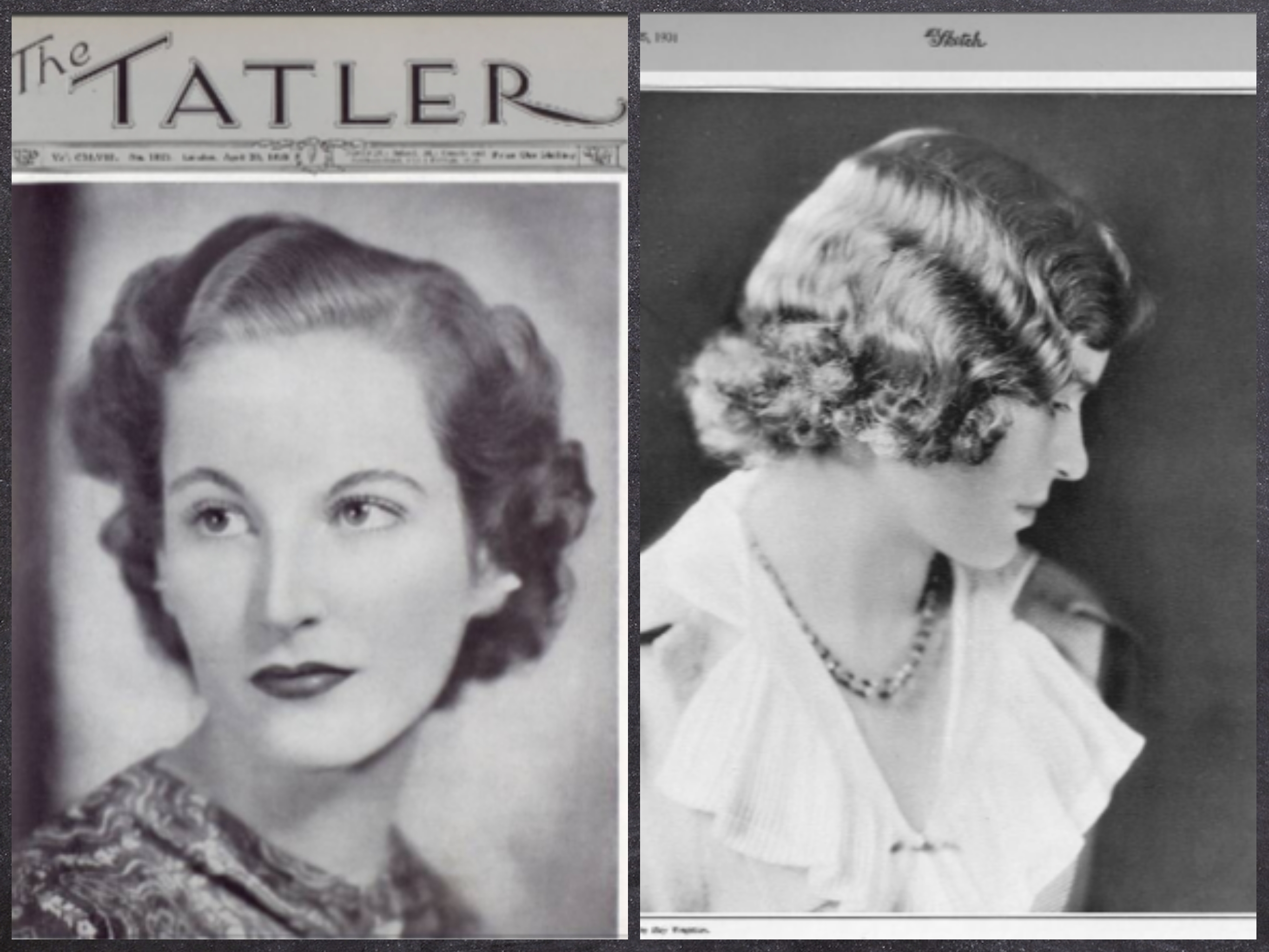

Nerissa and Katherine Bowes-Lyons were born to John “Jock” Bowes-Lyons, the elder brother of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, and his wife Fenella Hepburn-Stuart-Forbes-Trefusis in 1919 and 1926 respectively. Jock and Fenella had five daughters but their firstborn died a few days after her first birthday. A little before Jock and his wife started their family, Fenella’s sister, Harriet married and started a family of her own. She and her husband, Major Henry Nevile Fane, had seven children, one of whom died in infancy. Their daughters Idonea (b. 1912), Rosemary (b. 1914), and Etheldreda (b. 1922) were all born with severe developmental disabilities much like their cousins Nerissa and Katherine. If their condition was ever properly diagnosed then that information hasn’t been made available to the public. Accounts suggest that for the most part the girls were non-verbal and had a mental age of at most, six years old. They were reported to have little awareness of their surroundings and didn’t know of their relationship to each other.

Little is known of the upbringing or early lives of the girls but we do know a series of events and the dates on which they occurred. In 1930 Jock Bowes-Lyon died leaving his widow with four children to care for. In 1936 Edward VIII acceded the throne and abdicated in the same year. As a result, his brother, Prince Albert, the Duke of York became George VI and Elizabeth Bowes-Lyons went from being married to a prominent member of the royal family to Queen of England.

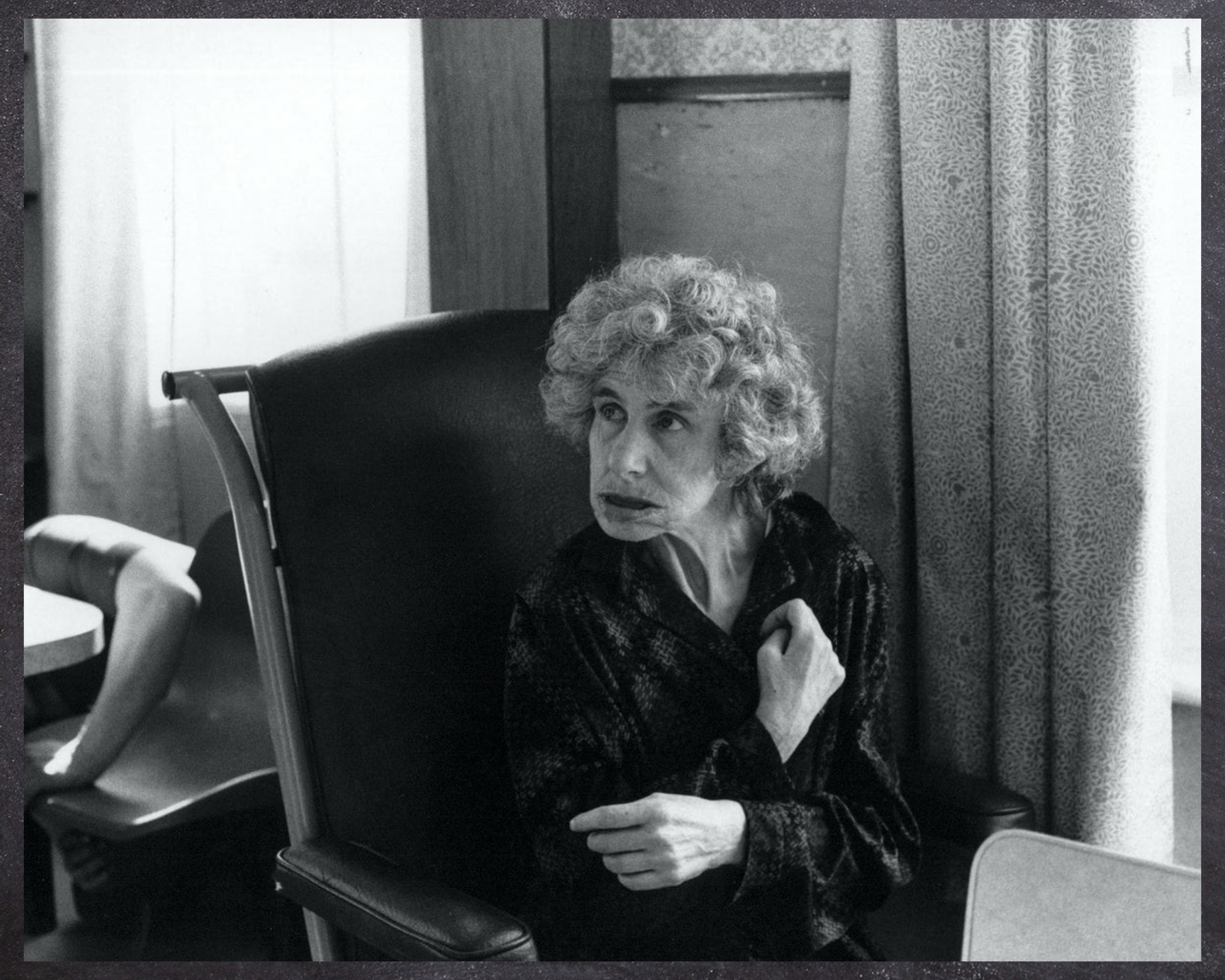

After the death of her husband, Fenella Bowes-Lyons spent much of her time in Paris while her daughters apparently remained in England. Allegedly, Nerissa, Katherine, and their cousins were placed in Arniston School in Hemel Hempstead which could cater to their needs and provide care for them. Fenella returned to Britain in 1935 for her eldest daughter’s coming out. Incidentally, a column in The Sketch, a weekly society journal, noted that Miss Nerissa Bowes-Lyons, one of the Queen’s nieces, would soon be turning eighteen and would therefore make her appearance as a debutante as her sister had. Obviously, Nerissa made no such appearance but there was no follow-up in the same columns and her name was not noted again not even for her absence at that year’s ball.

Later, some newspapers would note that the establishment that the Bowes-Lyon girls attended closed down in 1938, returning them to their mother’s care now that she had returned full-time to London. In The Crown the Queen Mother suggests that her Aunt Fenella couldn’t cope with their care and this may have an element of truth to it as private nurses were increasingly difficult to hire, even for families connected to the Royal Family, thanks to the outbreak of war. Whether Fenella could cope or not, in June 1941 her father, Charles Hepburn-Stuart-Forbes-Trefusis, arranged for his granddaughters Nerissa, Katherine, Idonea, Rosemary, and Etheldreda to be committed to Earlswood. This isn’t to say that the rest of the family protested the arrangement or even that it was his idea but one of the few facts we are aware of is that all five girls were placed into Earlswood together, on the same day, and it was their grandfather who funded their initial move.

In 1986, Nerissa died at Earlswood aged sixty-seven. Her funeral was attended by some of the hospital staff who had cared for her and without any money provided for a burial, a pauper’s grave was provided at Redhill cemetery. She was laid to rest in a plot marked only by a tag with a serial number written on it.

Exposure and claims of cover-up

It would later be claimed that Nerissa’s death and burial prompted media interest in the girls. Whether this is true or not, the following year a journalist for the British tabloid The Sun visited Earlswood. Posing as a relative, he managed to meet and photograph Katherine. The story was then printed under the headline ‘Queen’s Cousin Locked in Madhouse’

The British press practically exploded with the scandal, revealing that of the five girls that had been committed to Earlswood, three of them were still alive, but their care and lifestyle did not reflect their positions. Some years earlier, Earlswood had been renamed the Royal Earlswood Hospital when it became part of the National Health Service. More significantly, when it joined the NHS, the cost of the care of its patients, including the Queen’s cousins, became the responsibility of the general public. But this was considered one of the most minor points. Far more pressing was the issue of apparent negligence; not of the care facility but of their families.

The press reached out for comments from the NHS, the hospital, the Royal Family, the Bowes-Lyons, doctors, and the list goes on. The hospital could only confirm that the women were patients and had been there for a long time. The Royal Family would only say that it was a private matter for the Bowes-Lyon family, a stance which hasn’t changed since the story broke in the eighties.

A spokesman for Lord Strathmore, the Queen Mother’s nephew and head of the Bowes-Lyon family, said, “the whole thing is news to us.” Which was the attitude reflected, with one exception, among all the members of the Bowes-Lyon family. The only one to suggest any differently was Lord Clinton, a grandson of Harriet Fane. He released a statement in which he said, “I have known for some time about the whole business. It’s a family matter. If I am going to say anything further, I want to say the right thing so there is no confusion.”

With Lord Clinton the only one who seemed to have any notion that these women even existed, there was public outrage that they had been abandoned and forgotten without any visitors. Earlswood would go on to say that they received hundreds of bouquets of flowers for Katherine from well-wishers. Meanwhile, the papers uncovered further revelations. According to Burke’s Peerage and Debrett’s, both the authority on aristocratic families and their lineage, Nerissa had died in 1940 and Katherine in 1961, information which had been provided to them by the Bowes-Lyon family.

Lord Clinton denied that there had ever been a conspiracy to hide the women from public view and that Fenella had always been a vague woman who had either filled out the forms incorrectly or more likely, not filled them out at all. This explanation was rejected by Harold Brooks-Baker, the editor of Burke’s Peerage who said, “any information given to us by the royal family is accepted. Even if we had evidence to the contrary, we would put in any information given to us by any member of the royal family.” (More on these statements later).

While Fenella was thought to have visited them until her death in 1966 (incidentally, three years after Debrett’s and Burke’s Peerage had erroneously listed her daughters as dead), according to interviews with the Earlswood staff, they received no other visits from anyone else in their family. Nor did they receive birthday cards, holiday cards, or any kind of recognition.

In 1982, volunteers at the hospital wrote to the Queen Mother to inform her that her nieces were still alive but no money was being supplied to buy them anything beyond what the NHS could supply them with. The Queen Mother replied with a cheque to buy them toys and sweets at intervals in the coming years and included a note to say more could be provided in due course. By the time the press had gotten hold of this information in 1987, it had been five years and no further request for money had come but neither had any acknowledgement from the Queen Mother. Her behaviour was considered callous, even more so in light of the fact that she became a patron of Mencap, the UK charity for people with learning disabilities, the same year that Nerissa died.

For all of these revelations and reactions, however, the one that incurred the most vocal criticism, even from newspapers that supported the royal family’s actions, was that Nerissa had been buried in a pauper’s plot without a headstone. This was singled out as the cruellest of actions when they were already being condemned for cruelty by shutting them away in the first place.

The Hidden Cousins

That the five girls had been hidden away for their entire lives is undeniable. Aside from the one mention of Nerissa’s coming out which didn’t happen, their names were absent from the society pages that followed their families and regularly featured their siblings. Katherine and Nerissa weren’t present at any family functions which were reported in the same pages; notably their father’s funeral, their sisters’ weddings, and their aunt’s coronation. Their cousins went on to be deeply involved in royal life, some becoming attendants on their aunt at court, while their sister Anne became Princess of Denmark, and we’ve seen from their own admission that many of these relatives were led to believe Nerissa, Katherine, and the others had already died.

Given that it was the unfortunate norm to put mentally disabled relatives into institutions where they would at least receive full-time care, in this regard there was nothing particularly sinister about what the families did. It seems that the girls were cared for in small, private facilities prior to 1938. Then there was a two-year gap which may have seen them cared for by private nurses until the inevitable shortage caused by the progression of the second world war. Thus, they entered Earlswood.

The fact that they were hidden from society is nothing particularly new. Prince John, George VI’s brother, was withdrawn from public life from the age of ten to disguise his developing epilepsy. The condition proved fatal but the public knew nothing of it until after his death at thirteen. However, there is a significant difference between keeping the girls from the society pages and outright giving out that they had already died.

We’ve already seen that Lord Clinton suggested that the provision of death dates was a mistake committed by his aunt who had never filled out the appropriate forms properly. However, this has largely been rejected in the court of public opinion which points to the specific and different dates that she gave for the deaths of Katherine and Nerissa when the other information was correct. In her initial statement, Lady Anson revealed that her family had been led to believe that her aunts were dead, a stance supported by her many cousins who gave statements to the press saying they were shocked to learn they were alive and housed in Earlswood.

This is, ultimately, the issue at the heart of the scandal. In hiding the girls from their own families it gave the impression of callousness which seemed exemplified in the lack of care over Nerissa’s resting place. As the press continued to publish stories about the situation, including revelations about another cousin, Jean Bowes-Lyons, who spent much of her life in a similar institution, the statements from the families changed. Lady Anson who had initially said that the family thought Nerissa and Katherine were dead, went on to say that they were much-loved members of the family who had received regular visits from their mother. Other relatives also attended until the nurses intervened and asked them to stop because they were upsetting the girls who were only capable of recognising their mother. A nurse who cared for the girls at Altringham also came forward and said that the Queen Mother, then the Duchess of York, had been a regular visitor and had brought them gifts. However, these statements conflict with interviews given by the staff for a Channel 4 documentary in which they all resoundingly said that they’d never seen anyone visit beyond Fenella.

Aftermath

At the time of the revelations, three of the Queen’s cousins were still alive; Katherine Bowes-Lyons and Idonea and Etheldreda Fane. We’ve seen that there was a huge amount of sympathy for the cousins so we would naturally ask; what happened next? The answer is, disappointingly, nothing.

In 1996, Etheldreda died and was buried in Redhill with her sister and cousin, again in a pauper’s plot. Shortly afterwards, Earlswood closed and Katherine and Idonea were moved to Ketwin House in Surrey. Ketwin closed in 2001 and they were moved to a third care home but the location wasn’t disclosed. Idonea died in 2002 and was, like the others, buried in pauper’s plot in Redhill cemetery. Her death wasn’t announced for another year. Katherine died in 2014 and was buried in the same row as her sister and cousins. After her death, Fenella’s granddaughter, Lady Elizabeth Anson, maintained that Katherine had received regular visits throughout her life, a claim disputed by the staff of the hospital who were the only attendants at Katherine’s funeral.

Interest in the cousins was briefly renewed with the release of season four of The Crown and apparently, the queen was distressed at the portrayal of what happened to Nerissa and the others. The episode presented a largely fictionalised version of events. Princess Margaret likely did not go on a hunt for her missing cousins and if she had, then she would not have met all five of her cousins, as two of them had already died at the time shown.

The motives of the family have also been questioned and the fictional Queen Mother’s claims that the girls were all committed for the sake of the perception of the monarchy’s bloodline have been largely rejected as the explanation. For a start, medical science was not so far behind that genetic conditions couldn’t be separated by families. Whatever condition affected Nerissa, Katherine, and their Fane cousins had nothing to do with either the Bowes-Lyons or the Windsors.

Among the aristocracy, there were rumours of the ‘mad blood’ among the Trefusis family but that had nothing to do with the royal family. It’s extremely unlikely that the cousins would have been shut away to protect a bloodline that they weren’t linked to by blood. The timing of their committal also suggests that Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon’s coronation wasn’t the driving force behind it. By the time they were placed in Earlswood, she had been queen for five years. The most likely explanation isn’t particularly dramatic but it does reflect the attitudes towards learning disabilities of the time. The unfortunate truth is that medical advice at the time was to have relatives with such disabilities shut away in institutions such as Earlswood. Ultimately, the Queen Mother maintained her position as a patron of Mencap because Mencap’s own advice at the time had been, in the words of the organisation’s secretary-general; “to put them away and forget about them.”

Eventually, Nerissa’s surviving cousins, Lady Anson among them, contributed to a new headstone for her grave. Despite this, for all the public sympathy, and the family insistence that the girls were all much-loved cousins, they were buried in pauper’s plots as recently as eight years ago, thirty years after the initial revelations.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.