On April 18th 1912, the RMS Carpathia arrived in New York City to disembark seven hundred passengers. The seven hundred were not their own. They were survivors of the RMS Titanic which had sunk six days earlier after striking an iceberg during its maiden crossing to New York. The sinking had generated incredible media coverage with the press flooding the port in order to get the full story of what had happened; something which could only be speculated on until the survivors reached land. Until then, there was a flurry of confused reports based on fragments of misunderstood wireless messages. At one point, it was thought that the Titanic hadn’t sank at all. It was being towed into the Canadian port of Halifax with all passengers and hands accounted for. The story would change several times to varying degrees of disaster and it was only when the Carpathia docked that the full tragedy became apparent. The Titanic had been carrying fifteen hundred passengers and crew which meant over eight hundred had perished.

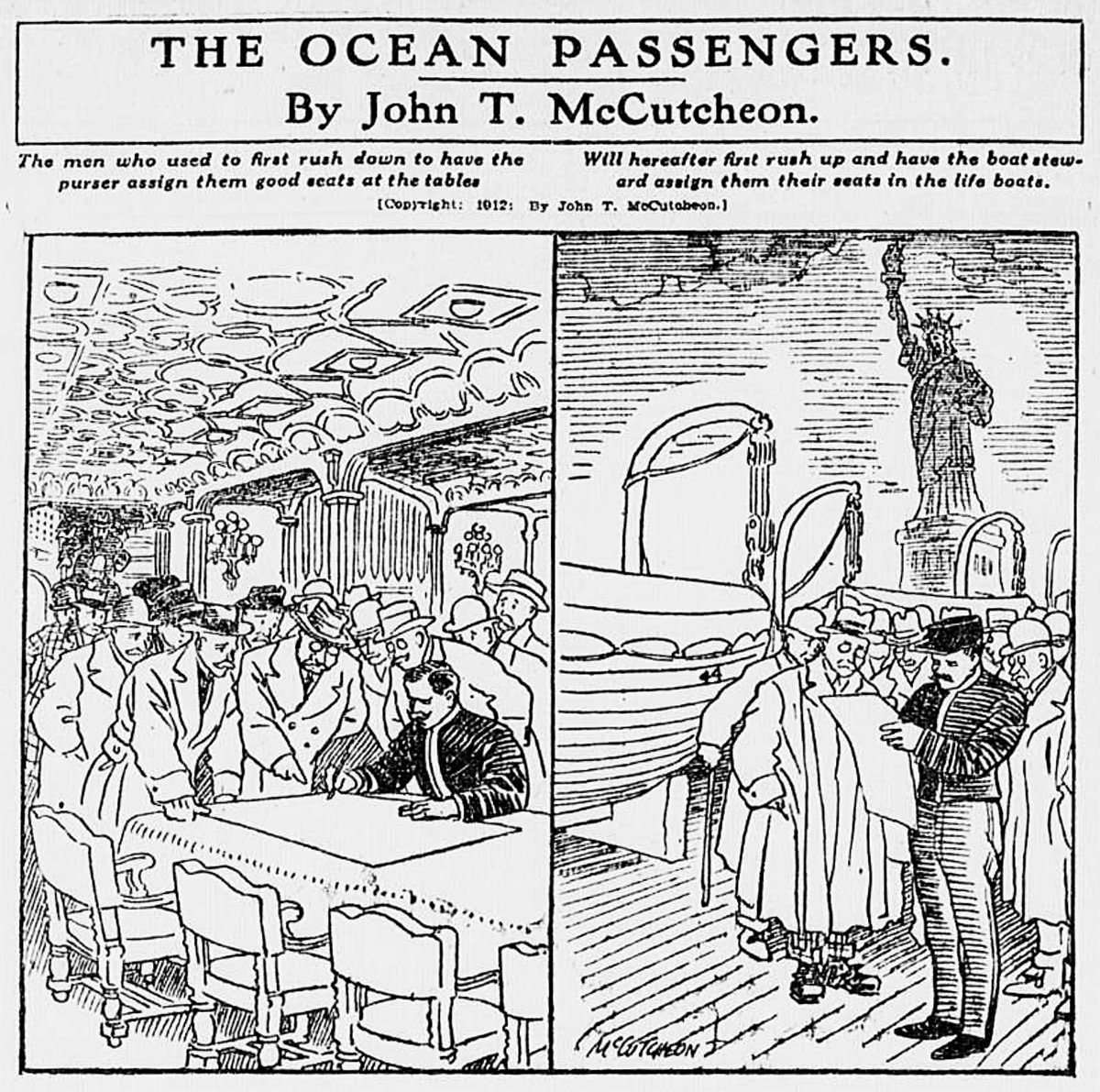

As dramatic stories of survival and loss circulated, a clearer picture of survival emerged. More than anything class became the most significant factor in terms of survivor demographic and beyond that; gender. Only twenty percent of the men aboard Titanic survived compared to seventy-five percent of the women and fifty-two percent of the children. In 1912, the image of the ‘gentleman’ was a prominent one in society. A gentleman was well-mannered, patient, level-headed, and above all chivalrous. The men who had gone down with the ship were largely presumed to be heroes who had done their gentlemanly duty by allowing women and children to vacate the sinking ship in their place.

What followed was an outpouring of praise for the values of these ‘true’ gentlemen. A large number of the men were among the world’s rich and famous so their deaths would have attracted anyway but the manner of their deaths allowed them to be effusively praised for their bravery in helping women into lifeboats and stepping back, knowing that they were going to die. Their sacrifice became the stuff of legends and they were immediately mythologised. Even the men who weren’t apparently swinging from ropes to drop babies into lifeboats were praised immensely for their calm and quiet dignity as they stood aside and let others survive.

As the Carpathia docked and the full situation became known, stories of how the great and the good observed the rule ‘women and children first’ flooded the media and the public imagination. Dr. Henry Van Dyke, renowned author, professor, and clergyman delivered some remarks in Princeton, addressed to the survivors the same day that they arrived in New York. There he talked about how “a man is stronger than a woman, he is worth more than a woman, he has a longer prospect of life than a woman. There is no reason in all the range of physical and economic science, no reason in all the philosophy of the Superman why he should give his place in the lifeboat to a woman.” With men being so much more valuable than women in every regard, the men who died at sea could be seen to have died of a surfeit of decency rather than hypothermia or drowning.

But these men stood aside – one can see them! – and gave place not merely to the delicate and the refined, but to the scared Czech woman from the steerage, with her baby at her breast; the Croatian with a toddler by her side, coming through the very gate of Death and out of the mouth of Hell to the imagined Eden of America.

Logan Marshall – On Board the Titanic

(for real though at some point I’ll be writing about Titanic and race because there’s a lot to unpack there)

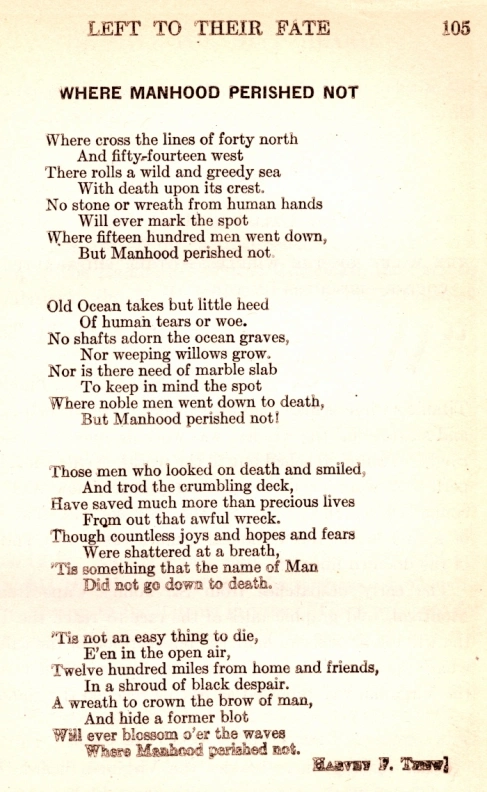

Poems and prose written at the time (and there were a lot of them) echoed the sentiment that the men had courageously sacrificed themselves to save the women as part of a higher ideal. One in particular, ‘Where Manhood Perished Not‘ captured the idea that the men might have died but ‘manhood’ and the concept of being a gentleman had never been stronger.

As hero worship for the men who had died mounted, attention turned to those who survived. How could any man have taken a place in a lifeboat when there were still women and children aboard the ship who went on to die? Only twenty percent of the total men aboard Titanic survived but in light of the loss of so many women and children, this twenty percent now found themselves under the microscope of public opinion and had to justify their survival. They weren’t helped by circulating stories of men resorting to bribery, disguising themselves as woman, and/or hiding themselves in the lifeboats.

For the most part, there was no grand conspiracy to favour the men who found themselves in a lifeboat. As a general rule; the men who survived in the lifeboats were there because they’d been on hand when an officer called them forward to enter it. Initially, the officers found it difficult to convince women to enter the lifeboats at all. The passengers simply didn’t want to leave. The ship seemed a much safer bet than the comparatively flimsy lifeboats. It was cold, the lifeboats uninviting, and hardly anyone aboard had grasped the reality that the ship was going to sink. In the absence of women and children, and with women refusing to leave the deck, men were invited to take a seat. Something to note, because it will become relevant later, is that men were more likely to find a place on the starboard side of the ship, under the charge of First Officer William Murdoch. When he could find no more women and children, he turned to the men as a matter of course. On the other side, Second Officer Charles Lightoller interpreted it as women and children only and prevented any men beyond crew from boarding them, even when there were spaces available.

In light of how many men were found to have helped women into the lifeboats and then stepped back (most of whom incidentally were found on Lightoller’s side of the deck) and increasing stories of their heroism or, at the very least, their dignity, the public started to question the survival and character of the surviving men. You’d think this would be limited to the men who found themselves in a largely empty lifeboat rather than the crew required to man them but you’d be wrong. As we’re about to see, there were instances where even the men assigned to the boats to keep the passengers alive found themselves receiving public scorn. We’re going to look at the criticisms levied at the individuals and groups that survived, considering where they came from, what they were rooted in, and how they affected the accused. Before we do, there’s just a point to bear in mind and it is that these criticisms were so prevalent that a great number of men who survived Titanic were viewed with the same kind of disdain as conscientious objectors to the war that would shortly plunge the world into disaster. This is just to give some kind of scope for the feelings that we’re going to be talking about. We aren’t talking about attitudes limited to a vocal minority. As a rule, if you were a man and survived Titanic you were a coward unless you had a bloody good story to justify yourself, something which the surviving passengers were aware of as they disembarked in New York.

God knows, I’m not proud to be here. I got on a boat when they were about to lower it and when, from delays below, there was no woman to take the vacant place. I don’t think any man who was saved is deserving of censure, but I realize that, in contrast with those who went down, we may be viewed unfavorably.

Unknown First Class passenger to the media upon leaving Carpathia

The Crew and other Seamen

The male crew members of the Titanic were, theoretically at least, doomed. As men, they had to give up their places in boats to women and as crew they had no place in the boats unless they were specifically required to man them; jobs which were mostly given to the deck crew and stewards who were on hand and helping to load them in the first place. There were also men who through various corporate technicalities didn’t count as either passenger or crew even though they had clear jobs on Titanic. The band for example who famously played as the ship went down, were not employed by the White Star Line. They were contracted out to the company which provided musicians for passenger liners. The A La Carte Restaurant found in first class operated privately under the direction Luigi Gatti who owned the same restaurant on the Titanic’s sister ship Olympic. The staff employed by him were employed by him and they had no standing among the crew. Neither were they passengers, and as the lifeboats were launched, accounts claimed that the various cooks, cashiers, and restaurant staff had been blocked from entering the boat deck by the stewards. Of the sixty-six staff, three survived (only one of whom was a man) and Luigi Gatti who had been travelling to ensure there were no maiden voyage problems in his restaurant died in the sinking.

The survival of so many stewards was welcomed as they were so involved with the passengers throughout the journey that they recognised them, they knew them, they had relationships with them. As such, it was the stewards who knew more than anyone else about where various passengers were when they died. It was the Bedroom Steward, Henry Samuel Etches, who returned with the famous message from Benjamin Guggenheim, ‘tell my wife that I’ve done my best in doing my duty.’ In many, many cases, without the stewards we’d have no stories of passenger and crew movements as the ship went down. They’d just be listed as having gone down with the ship.

Special praise was reserved for those crew who had done their duty, whatever that may be, went down with the ship and still managed to survive. Second Officer Lightoller was one of those who remained on deck until the ship foundered. He and some others managed to swim clear of the suction and came across collapsible lifeboat B which was floating overturned. They climbed aboard the boat and spent the night trying to keep the boat balanced, under Lightoller’s direction, until they were taken off as the Carpathia arrived. Lightoller exemplified the duty of the crew, the heroism in the manner of his survival and the tragedy as many on the boat and around it died in the night. The praise directed at such men contrasted greatly with the ire towards some of those who were assigned to lifeboats and deemed to have taken places from more deserving and heroic crew.

One of the most damaged was Quartermaster Robert Hichens. He was steering the Titanic at the time of the collision and in later years it was suggested that he had been ‘the man who sank the Titanic‘ by misunderstanding his instructions and inadvertently steering the ship right into the iceberg, causing the fatal blow. Given his many years at sea, it’s unlikely that he made such a mistake but incredibly, this accusation was not the worst to haunt him. Far more damaging were the allegations that in the boat he had been derelict in his duty, drunk, and rude to the ladies in his charge.

Hichens was assigned to lifeboat number six by Lightoller who went on to fill the boat with about twenty women. The ladies in the boat gave testimony that he was rude, that he swore often, that he was drunk, that he monopolised the only blanket available, that he refused to row, and that he dismissed the calls to return to pick up survivors in the water with the callous remark; “We are to look out for ourselves now, and pay no attention to those stiffs.” His behaviour was picked up by the media as a number of the women were first class passengers. One of them was Margaret Brown who went down in history as ‘the unsinkable Molly Brown’ because of her efforts on behalf of the women of Titanic and so her criticism was repeated and reprinted in a number of papers.

Another of the woman in the boat, Mary Smith, whose husband of only two months was held up as an example of one of the more heroic men aboard the Titanic, gave evidence at the US inquiry into the disaster.

Our seaman was Hichens, who refused to row, but sat in the end of the boat wrapped in a blanket that one of the women had given him. I am not of the opinion that he was intoxicated, but a lazy, uncouth man, who had no respect for the ladies, and who was a thorough coward.

Mary Eloise Smith (First Class passenger) – US Senate Inquiry Statement

Hichens himself gave evidence at the same inquiry in which he defended himself against the accusations. He claimed that the blanket in question was half wet, that he was sure he had rowed, that his language was irrelevant, that he was drinking brandy but not enough of it to get drunk, and that he would never have used the word ‘stiffs’ in relation to the bodies in the water as he would have used other words to describe them. He ended by saying that the women were getting on his nerves by criticising him in the press. Needless to say, his defense didn’t endear him to the public. His life would be blighted by public opinion and the intense scrutiny that came with it. Hichens’ life was marked with alcoholism, divorce, and while on remand for attempted murder, he tried to kill himself on two occasions. He died three years after his release from prison of heart failure.

He wasn’t the only one to suffer consequences for his behaviour in that lifeboat that night. Enter: Major Arthur Godfrey Peuchen.

Major Peuchen was a Canadian businessman, prominent military officer, and first class passenger. He was the only man that Lightoller permitted to enter a lifeboat. As lifeboat six reached the water, Hichens called up to Lightoller that with only himself and one other member of crew (one of the lookouts) he couldn’t man the boat himself. Lightoller called for sailors but the deck crew had already moved on to releasing the next boat. Major Peuchen stepped forward and offered his assistance. When Lightoller asked if he was a seaman, he replied that he was a yachtsman. He was, at various times, Vice Commodore and Rear Commodore of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club, and Lightoller told him that if he were seaman enough to lower himself into the boat by rope then he could get aboard. He managed it, took a seat among the ladies and helped row the lifeboat away from the ship.

You’d think that Peuchen, a volunteer offering to assist, would be exempted from the criticism that he survived. So it’s surprising to see that actually he was one of the very first to be criticised.

When the first order was given for the men to stand back, there were a dozen or more who pushed forward and said that men would be needed to row the life-boats and that they would volunteer for the work. The officers tried to pick out the ones that volunteered merely for service and to elimite those who volunteered merely to save their own lives. This elimination process, however, was not wholly successful.

Logan Marshall – On Board the Titanic

The above quote was published in a book of observations, stories, and testimony released just weeks after the disaster. It immediately drew attention to the men who volunteered to man the boats out of cowardice (if there could be such a thing) and as Peuchen was the only man to have done so, it fell on his head. It might not have done so if he had ended up in any of the other boats. But his presence beside Hichens attracted scrutiny. As well as being a business magnate and member of a multitude of well known clubs, he was also a decorated military officer. A year earlier, he had performed a ceremonial role in the coronation of the new King and Queen of England. A man of such standing could surely not sit by while Hichens spoke to the women so rudely.

In New York, Peuchen gave a number of interviews in which he discussed how he came to find himself in the boat and the necessity of his presence. It was somewhat embarrassing for him when it started to become known that it was Molly Brown who had been the real hero of the boat and that Peuchen himself had had to be encouraged to row. He was also known to have made disparaging remarks about the deceased Captain Smith and by extension the crew of the Titanic which he repeated in earnest to the media. He repeated his criticism at the US Inquiry but misjudged the public support for the Captain who had gone down a hero.

By the time he returned to his home in Toronto he was hardly considered one of the heroes of Titanic. Criticism of him was rife, mostly centered on the accusation that whatever his experience, he had volunteered himself as a seaman just to get off the sinking ship. “He said he was a yachtsman so he could get off the Titanic, and if there had been a fire, he would have said he was a fireman.” His social standing plummeted and never recovered. He was eventually dismissed from the Royal Canadian Yacht Club and his other club activities diminished considerably. The line between hero and coward for the men of the Titanic was incredibly thin and Peuchen was one of many who fell in with the cowards. He went as far as acquiring a note from Lightoller confirming that he had only entered the boat under orders (in as much as they applied to him). Lightoller obliged but the very fact that Peuchen asked for one only proved to his many critics that he was aware that he should never have been in the lifeboat in the first place. The man simply couldn’t win and he wasn’t the only one.

The Husbands

Many men accompanied their wives into the boats and for that they could surely be forgiven. Except, for every husband who attended his wife, there were three more who had helped their wives into the boats and stepped back.

John Jacob Astor was the richest and greatest of celebrities aboard Titanic. Everyone knew that he was returning from his honeymoon with his young bride. Headlines like the one above were printed before the Carpathia docked which meant that before the returning husbands had even stepped foot in New York everyone and their Airedale Terrier knew that Astor had died having secured his new and young wife. To add further fuel to a fire that really didn’t need it, young Madeleine Astor was pregnant. If anyone could have used their wealth or position to take a place in the lifeboat it was J. J. Astor. The fact that he didn’t meant social death for every other husband who survived.

For most of the husbands there was no great drama in how they came to sit beside their wives. With the exception of Lightoller, officers were happy to let men into the boats where there were no women available. In some cases they were allowed entry so that they might encourage some of the more reticent women on deck to actually abandon the ship. These commonplace stories were related to the various media outlets looking for a story right up until it became clear that the public might not be entirely on their side. Suddenly, it seemed that none of the husbands had wanted to get into the boats but through some means or other, they inevitably ended up beside their wives.

Mrs Helen Bishop and her husband, Dickinson, who were both travelling in first class, were among the first to enter lifeboat seven which was launched from the starboard side of the ship. It was one of the first boats to leave, passengers were reluctant to enter it, and they were offered a place. In her interviews with the press, Helen spoke of how the officer had called specifically for brides and grooms, wanting to get any newlyweds and honeymooning couples off the ship first. Helen and Dickinson were returning home after a four-month honeymoon and yielded to the officer’s insistence that they enter the boat. She claimed they joined three other couples and that the men on deck couldn’t be persuaded to join them despite the available places.

There was actually only one other married couple in the boat; Nelle and John Snyder. Like the Bishops, the Snyders were invited to take a seat calmly until the story changed to suggest that John had been physically lifted into the lifeboat by one of the officers. Similar stories started to emerge from couples in similar situations. Albert Dick from lifeboat three claimed to have been embracing his wife, bidding her farewell, when an officer pushed them overboard so that they landed in the lifeboat as it lowered. Elsewhere, Juliet Taylor told how her husband persuaded her to get into a lifeboat before he, and several other men, were allowed to take the seats. Meanwhile, her husband, Elmer Taylor’s account had the lifeboat being lowered when an officer begged the couple to take the final two seats before it was too late.

Single men travelling alone had even less justification to find their way into a boat but that surely did not stop them trying. One observer from the media noted: “Every man among the survivors acted as though it were first necessary to explain how he came to be in a lifeboat. Some of the stories smacked of Munchausen. Others were as plain and unvarnished as a pike staff. Those that were most sincere and trustworthy had to be fairly pulled from those who gave their sad testimony.”

Cowards, Crossdressers, and Crooks

In the weeks following the disaster, almost every man who survived in a lifeboat faced accusations of cowardice, disguising themselves as women, or bribing their way onto the boats. These stories were based somewhat in fact but unsurprisingly blown hugely out of proportion by the media. Before I run through where these stories originated, I feel like I should point out that I’m not casting a moral judgement on any of the men involved which is more than what James Cameron managed.

An accusation of cowardice could mean different things depending on what class the passenger was in. A first class passenger was a coward if he accepted a place in a lifeboat without hesitation. Far worse though were the gentlemen who jumped into the boats as they left Titanic. For third class men, cowards were those who snuck aboard the lifeboats while the officers weren’t looking or who stowed away through some means or another.

In lifeboat six, Philip Zenni, having been denied access to the boat twice already, leapt into the boat while the officer’s back was turned and quickly hid under the seats. He wasn’t discovered until after the ship had sunk, at which point nothing could be done about it. As a third-class passenger, Zenni hardly had to suffer the condemnation of his peers but several gentlemen who survived were accused of hiding themselves underfoot. The reverse was true of Dr. Henry Frauenthal and his brother who allegedly jumped into lifeboat five after it had already been lowered. In doing so, one of them landed heavily on fellow first class passenger, Annie May Stengal, injuring her in the process. After the fact, the story of the foreigners from third class who threw themselves into a boat and injured the escaping ladies became part of Titanic myth. Even when insulting the survivors, it was apparently a step too far to think that a gentleman of standing might have behaved in such a manner.

There were similarly few examples of men who had disguised themselves as women to find their way onto a lifeboat compared to how many men suffered the accusation. There was only one verified account of such a man. Daniel Buckley, travelling in third class had struggled to find his way to the boat deck, having been obstructed by various stewards, one of whom allegedly locked one of the gates that allowed the steerage passengers to access the rest of the boat. Having found his way into a boat, he was ordered out at gunpoint.

Convinced he was going to die, Buckley curled onto the deck and started to weep. A woman in the boat threw him her shawl which he wrapped around himself. Mistaken for a woman, he was allowed into a boat where he wasn’t discovered until Fifith officer Lowe transferred him and others into another boat at sea.

I waited until the yells and shrieks had subsided for the people to thin out, and then I deemed it safe for me to go amongst the wreckage; so I transferred all my passengers, somewhere about fifty-three, from my boat and equally distributed them among my other four boats. Then I asked for volunteers to go with me to the wreck, and it was at this time that I found the Italian. He came aft and had a shawl over his head, and I suppose he had skirts. Anyhow, I pulled the shawl off his face and saw he was a man.

Harold Lowe – US Senate Inquiry Statemen

Lowe described Buckley as an Italian simply because Lowe described everyone he considered to have behaved badly as an Italian. (There’s that race thing again). Buckley had a shawl but the accusations went as far as claiming that men were getting dressed up in full evening gowns and hats to deceive the officers, which simply didn’t happen. This was born from a story published in the New York Herald where first class passenger, William Thompson Sloper, was identified as “a cur in human shape, today the most despicable human being in all the world.” According to the paper, while more heroic men were helping women into the lifeboats, Sloper rushed back to his stateroom where he donned a skirt, hat, and veil. Suitably disguised, he returned to the boat deck where he slipped between the brave heroes and escaped with his life.

In reality, Sloper did no such thing. When the Titanic hit the iceberg, he was playing bridge with the actress, Dorothy Gibson, and a mutual friend. They accompanied Gibson and her mother into a boat and were allowed to board with them when Gibson asked. After arriving in New York, a reporter for the Herald arranged to interview Sloper only to find that Sloper had already promised an exclusive to his best friend who happened to edit the New Britain Herald. The reporter was slighted enough to publish the article denouncing Sloper as a coward. Sloper was persuaded from taking legal action against the paper and faced accusations of the deception for the rest of his life. If he had sued it likely wouldn’t have changed anything given that every other gentleman who survived face the same accusations even without a slanderous editorial.

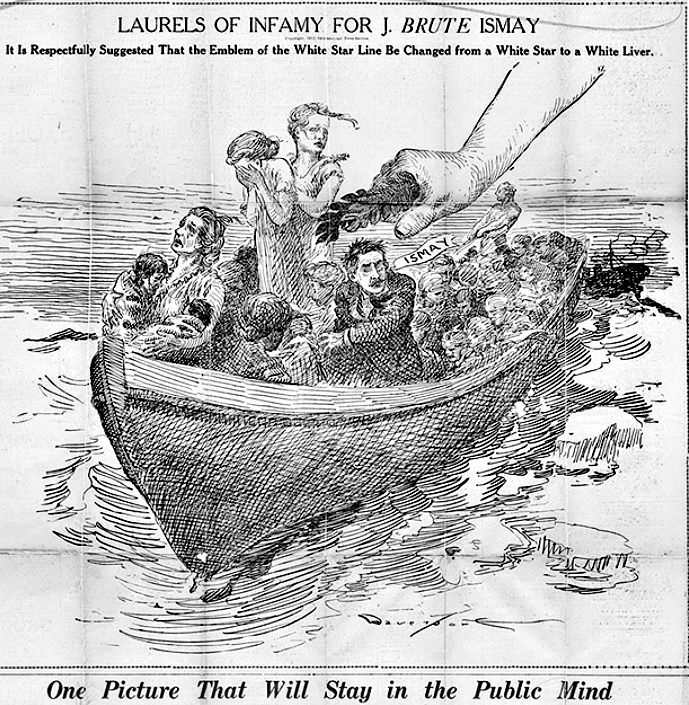

The Coward of the Titanic: Bruce Ismay

Without a doubt, the man who suffered most for his survival was J. Bruce Ismay who was branded, among other things, the great coward of the Titanic. Ismay was the chairman and managing director of the White Star Line. The Titanic was his idea and he was considered its owner. This put him in a kind of limbo where he was neither passenger or crew, yet somehow both. On the night of the sinking, Ismay helped a number of women and men into the lifeboats before he entered one himself. Initially hailed as a hero for his efforts, opinion rapidly turned against him and Ismay seemed to fall into the role of scapegoat willingly, possibly as a result of the severe post traumatic stress disorder that seemed to affect him when the ship was lost.

Ismay escaped in collapsible lifeboat C which was one of the last to leave the ship. There was some debate as to how he came to be in the boat with many suggesting that he had dressed as a woman (surprise surprise), or that he’d jumped in at the last moment (as shown in James Cameron’s Titanic). As with most of these stories, the reality was entirely less dramatic. Having helped everyone he could into the lifeboat and with nobody on hand to take a place, chief officer Wilde ordered him into the boat. This was corroborated by several witnesses and it was suggested that the order was given so that Ismay could give essential evidence as to what happened that night from his unique position as senior crew and passenger. Ismay himself confirmed that Wilde had done so in later life to his sister, but in the immediate aftermath he didn’t offer this information which might have saved him from the public pillorying that followed.

For the most part, Ismay didn’t seem to have been in any condition to confirm or deny Wilde’s order. In fact, by the time he came to the inquiries, he was unable to answer even simple questions like how long had he held his position correctly. Such things were seen as further proof of his weakness which was added to the list of things the press could criticise him for. He was critical of the Captain, it was said that he had personally vetoed the decision to add more lifeboats to the Titanic during its construction, and he had encouraged the Captain to press on at unsafe speeds while withholding ice warnings meant for the bridge. Added to this was his behaviour aboard the Carpathia. Upon his rescue, Ismay retreated to a private cabin and remained there in isolation for the duration of the journey while other passengers had to share cabins or sleep in the Carpathia’s lounges. He failed to furnish the White Star Line with a list of the surviving crew which allegedly (according to the press) caused two wives to die of suspense, and other passengers criticised how little help he had been to any of the survivors in the aftermath.

Ultimately, Ismay’s greatest crime was that of every other man who had gotten into a lifeboat. They had survived at the expense of women and children. Nothing could excuse or absolve them of this and with few exceptions their social standing slipped irrevocably. Ismay, ever the extreme example, became a recluse and despite maintaining correspondence with some other survivors, never discussed the matter with anyone in person. His wife went as far as to ban any mention of Titanic in his presence. Most of the other men who survived didn’t need to go so far but few of them wanted to draw attention to their actions on the night in question when even the most mundane of actions such as stepping into a boat, condemned them for life. Manhood perished not but every man who survived had surely forfeited their right to claim the virtue for their own.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents of titanic proportions, you can support me via my Patreon.