The Wonder (2022) is a period drama set in Ireland, 1862 in a community recovering from the Great Famine. Based on the book of the same name by Emma Donoghue, the film follows English nurse, Elizabeth Wright, as she is instructed to closely watch over Anna O’Donnell, a young girl who hasn’t eaten since her eleventh birthday four months prior. Elizabeth watches Anna in long shifts, traded with a nun, Sister Michael, trying to determine how the girl can live without food; is it a miracle or deception?

Anna O’Donnell is a fictional character created by Donoghue. No Elizabeth Wright was dispatched to the Irish Midlands to observe her and the story, as it unfolds, was invented. However, while The Wonder isn’t based on a specifically true story, it does draw from and is inspired by the phenomenon of ‘the fasting girls’. These girls appear throughout history but were particularly numerous in Britain during the nineteenth century. Although Anna didn’t exist, her story isn’t entirely untrue.

The earliest stories of girls surviving long periods of time without food are found in the Lives of the Saints. These accounts are filled with stories of girls devoting their lives to the Christian faith and facing persecution for it. The standard narrative had them pursued by a Pagan nobleman whom they would inevitably reject in favour of pursuing a monastic life. The nobleman would then imprison them, torture them, or maybe a fun combination of both. While imprisoned, the girl would be denied food yet when their cell was opened weeks later, they were found to be unaffected. During their imprisonment, they claimed to be nourished by the power of prayer or by angels who brought them manna from heaven, something echoed by Anna O’Donnell in The Wonder.

This theme continued in accounts of sainted women beyond the ‘Age of Saints’ and well into the Middle Ages. By then Christians were no longer persecuted for their faith so there wasn’t much call for angels to nourish starved women in prisons. Instead, women dedicating their lives to Christ would engage in long and frequent fasts that were considered more miraculous than they were devotional.

During the nineteenth century, there was a rise in young women claiming to have survived weeks or months without food. Modern explanations range from fraud, and hysteria, to anorexia, while contemporary explanations ranged from fraud, hysteria, and the miraculous. The girls attracted tourists and pilgrims from all over with some of the girls being thought to have acquired the ability to perform miracles as a direct result of their fast. Some of the girls were regarded as curiosities both religious and medical, so found themselves on display at museums, carnivals, freak shows, and human zoos. Others were investigated by the press and were denounced as frauds or praised as miracle workers depending on the leanings of the journalist.

A select few of the girls were investigated in a style similar to that shown in The Wonder. Doctors, nurses, and/or members of religious orders would watch over them. This could be done at the girl’s own home or in a hospital where she could be observed as closely as possible. These watches either revealed the girl to be a fraud by eating in secret, were inconclusive, or in tragic cases led to the girl’s death.

There were two cases that inspired a number of elements in The Wonder. They were the case of Ann Moore and Sarah Jacob known, rather originally, as ‘the fasting woman of Tutbury’ and ‘the fasting woman of Wales’.

Ann Moore

Ann Moore’s case came first. She was born in Derbyshire in 1761 and suffered in her early adult life. She married a farm servant and was possibly pregnant at the time. When the child was born, her husband rejected them and abandoned his new family, possibly because the child wasn’t his. Ann found work as a housekeeper for a widowed farmer and went on to have more children, this time by her employer. Eventually, she was forced to make her way to Tutbury where she found work in a cotton mill.

Impoverished and with her children to support, Ann began to be known for the small amounts of food she ate. By March 1807 she had been confined to her bed, suffering from stomach cramps and hysterical fits. Even the consumption of the smallest amount of food proved impossible for her. That July she ate a handful of blackcurrants which allegedly became the last thing she ever ate.

Her story was circulated and drew the attention of local doctors and surgeons and in 1808 a combination of medical professionals and neighbours determined to watch her for sixteen days. During the watch, public bulletins were issued describing any developments to keep the public updated on Ann’s condition. Nobody witnessed her eating or drinking anything and an account of the watch appeared in a medical journal. One of the doctors involved with the watch described her as ‘the most emaciated creature that ever existed.’ In the following years, her publicity grew which attracted travellers and visitors and Ann made a tidy sum from the resulting donations.

Another watch was organised in 1813 though Ann was reluctant to agree to it. She managed to successfully argue against being weighed to chart her progress; “If I should lose weight during the Watch, it will be scribed to the waste of my body for want of food. And if I should gain weight, it will be said that I contrived to obtain food in spite of the vigilance of the watchers. Either way, I shall be condemned by those who put any confidence in the weighing, and therefore I will not consent to be weighed.”

The watch took place in a two room cottage; one above the other connected by a staircase. Ann was placed in the upper room after it had been thoroughly searched and scrutinised. To ensure no food could be smuggled to her, a rope barrier sectioned off Ann’s bed and only the observers were permitted to cross it. The watch began on the 21st April and Ann immediately fell ill with a cold. Her condition deteriorated quickly and on the 30th April, her daughter demanded it stop. After a brief investigation, Ann revealed that her daughter had been smuggling her food, passing it into her mouth while kissing her goodnight. On 4th May 1813, she made a full confession to fraud in the presence of a magistrate and left Tutbury.

Sarah Jacob

The second case that inspired a number of elements in The Wonder was that of Sarah Jacob. Born in the Welsh village of Pencader in 1857 to a farming family, Sarah was one of seven children. In February 1867, at nine years old, she began suffering seizures after which she fell into apparent unconsciousness for a month. Although she regained consciousness, she didn’t entirely recover her health. She remained bedbound and struggled to consume any kind of food. She started falling into fits whenever she was offered food and could only manage the smallest mouthfuls. By October she refused to consume anything. Publicity was inevitable as stories of the miracle girl who refused food but suffered no ill effects. Some of the accounts referred to the ‘wonder’ of her countenance and likened her to saints which sparked rumours that it was the result of a miracle.

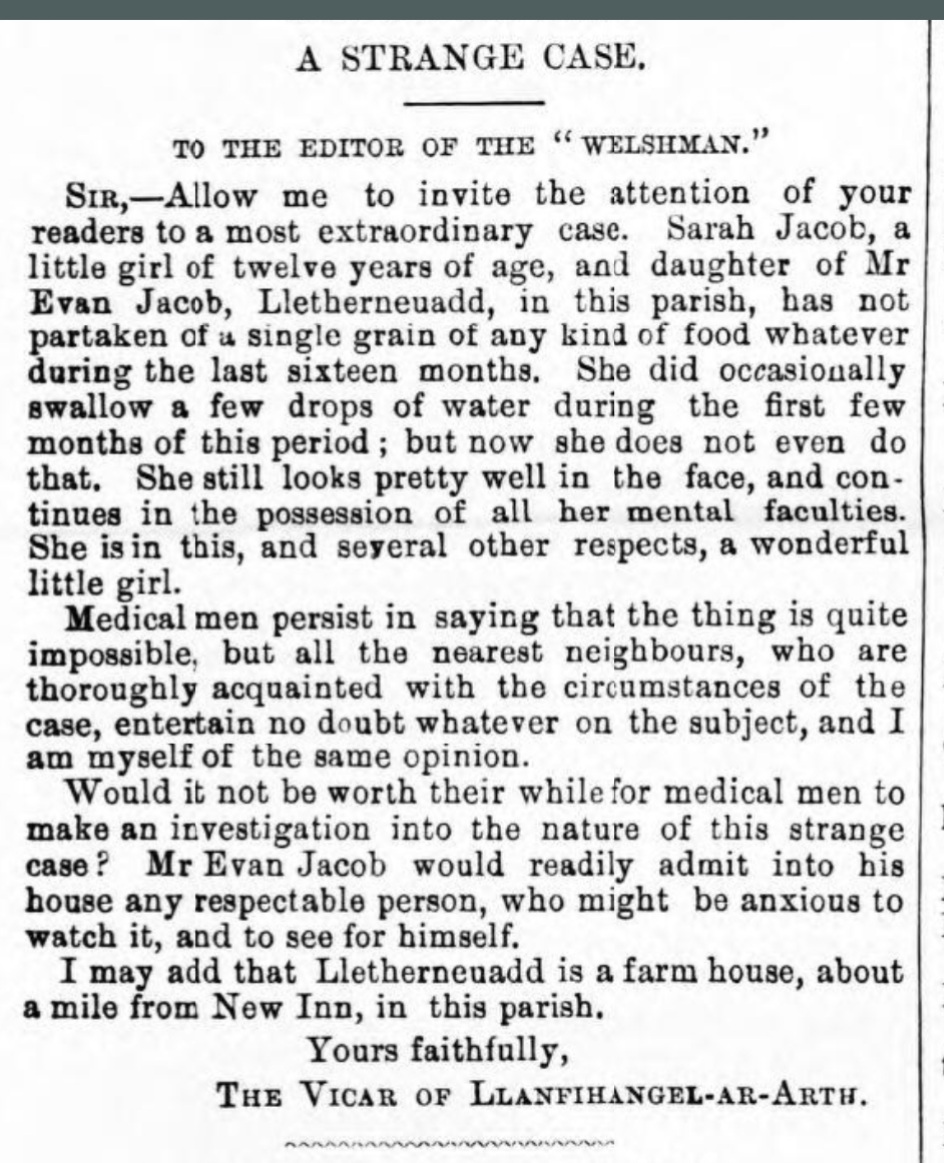

Her parents didn’t pressure their daughter into anything she didn’t wish for and allowed visitors to meet her. In February 1869, the local vicar wrote to the newspaper, The Welshman, and related her case. He suggested that doctors might be interested in studying Sarah and in the aftermath, there was an influx of visitors. Among them were a group of four ‘watchers’ who observed her for two weeks but they failed to witness her eating or drinking anything. An account of their observations was published in a county newspaper which only increased visitors.

Doctors began to visit her and her case was discussed in The Lancet, one of the most eminent peer-reviewed medical journals which attracted further attention. Although she was never observed to be eating, one doctor suggested that she was lying and eating by night. Such thoughts prompted calls for another watch and at the end of November a public meeting was held where the conditions of the watch were established. The bedbound Sarah was unable to attend herself but her father was present to sign the agreement on her behalf.

Four nurses from Guy’s Hospital, London, and seven local doctors were given control of Sarah’s room and of Sarah herself. Her father signed a statement to that effect and a little over a week later the watch began. Sarah didn’t eat anything and her condition deteriorated rapidly. Although the point of the watch was not to deny her food, she didn’t partake, and one of the nurses went to her parents and begged them to give her some water. They refused and declared that she wasn’t to be offered anything. Eight days after the watch began, Sarah died on the 17th December.

An autopsy was performed and an inquest held in the following days. They discovered that she had died of ‘exhaustion from lack of food’ but they also found that she had been eating up until the start of the watch. With the cause of death established as entirely down to the absence of food during the eight days, the doctors involved and Sarah’s parents were summoned before the magistrates court. The doctors were reprimanded but her parents were tried and ultimately convicted of manslaughter. Sarah’s father spent one year doing hard labour in Swansea prison while his wife was sentenced to a lesser six months. It was one of the only examples of a fasting girl where criminal charges were brought against those involved.

If you’d like to join me for more fun and games in picking apart history, and other behind the scene tangents, you can support me via my Patreon.