You are about to come with me on a journey into a wild rabbit hole. It started while perusing the list of survivors on the RMS Titanic, as one does, and discovering the survival of one William Wright. Wright was a crewman aboard the Titanic and his position was described as ‘Steward of the Glory-Hole’. Because I am fundamentally a child, I had to learn more about where such a name had come from. And so we enter the rabbit hole.

The ‘Glory-Hole’ referred to the stewards’ quarters, not just on the Titanic but on every passenger ship and crew liner. It allegedly came from an old Gaelic word ‘glaury’ which referred to the equivalent of a janitor’s closet. It’s a cupboard of miscellaneous items where odds and ends are stored. Aboard a ship, it was thought to stem from the rooms used by the stewards for their various supplies. Stewards of the Glory-Hole were therefore responsible for the maintenance and cleaning of the stewards’ quarters in the same way that the stewards were responsible for the maintenance and cleaning of the passengers’ cabins.

You’d think that’d be the end of it; a short and simple explanation. But it goes on. The corridor outside the Glory-Holes was always called ‘Scotland Row’ which referred to a street in London. Specifically, the street most notorious for queer activity and gay prostitution.

During the 1900s homosexuality was illegal but that’s not to say it didn’t happen, and there was a growing queer subculture in the cities, especially New York. The Bowery, a neighbourhood in Lower Manhattan, was the most visible example of this. Bars, cafes, and nightclubs had been established that catered exclusively to the gay community. One such place, The Columbia Hall (colloquially known as Paresis Hall), rented rooms to guests either for the night or by the hour and had a stage for female impersonations. They also rented a floor to an early transgender organisation allowing them to store womens clothing there given that it was illegal for men to wear them in public. Columbia Hall acted as a brothel and was connected to the other queer clubs by streets like London’s Scotland Row where queer prostitution flourished.

While the Bowery was often targeted by a hostile public and raided by the local police force, it was allowed to operate despite the illegality of what was being allowed to happen. It was, in effect, an extremely open secret. An inquiry into the area’s activities had the mayor and other officials denying any knowledge of the queer culture that existed there. The results of the inquiry focused entirely on the specifics of liquor licensing laws rather than any condemnation or crackdown of the clientele. The actual people were ignored. The surrounding middle-class society were happier to have queer communities exist in spaces where they could be ignored rather than have nowhere and potentially move into more “respectable” areas.

In response to this level of what could be considered freedom, the 1910s saw an exodus of queer people from Europe travelling to New York. And of course, they travelled on passenger liners like the Titanic. The liners themselves were almost havens for gay men and it was thought that two out of every six men working aboard were gay.

The uniform of a crewman allowed men to be fastidious about their appearance in a way that would have drawn attention in other facets of society. That’s not to play on stereotypes; at the time queer subculture was communicated through a secret language that incorporated style and dress into which a naval uniform fit quite nicely. On top of this, men working at sea in the travel industry could live without a wife or family and not fall under suspicion. Many gay men joined passenger liners as waiters, entertainers, but most often; stewards. Some of them would have wives and families at home but would have long-term male partners at sea. These partners might be fellow crewmates but the opportunity for stewards to have liaisons with passengers was rife aboard ships that were large enough to afford secret meeting places or dark corners where they wouldn’t be discovered. Sir Roger Casement’s controversial travel diaries revealed an entire culture of queer hookups aboard ships like Titanic where the other passengers were willing to look the other way. Much like the rest of society, unless these activities trespassed into their immediate sphere, they were prepared to ignore them.

And so we come full circle to the stewards’ quarters being referred to as the ‘Glory-Holes’. At this point, I think we can safely say that the name was a double-entendre. Officially, the name may have derived from a cupboard of miscellaneous items, but we can’t ignore the other implications. Glory-holes as we understand them in a sexual connotation had been around for almost two hundred years, available in ‘cottages’ or public toilets. It seems a stretch to think that the people who knew what cottaging was and would have been aware of the amount of gay men employed aboard passenger liners, were just naming the steward quarters after an ancient word for cupboard.

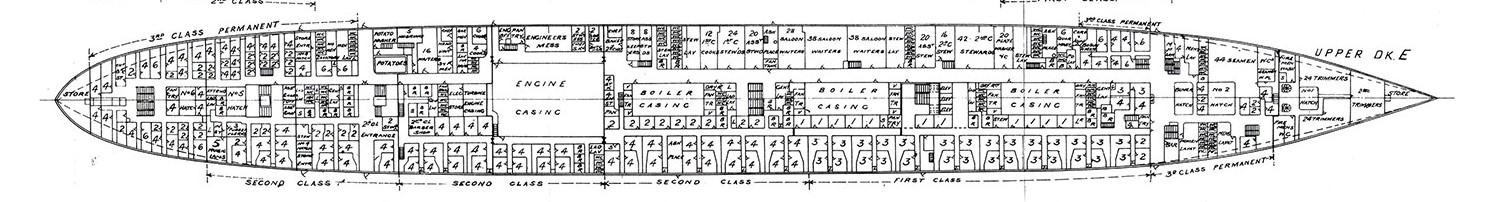

The stewards of the glory-hole weren’t more likely to be homosexual by association, whatever their unfortunate job title. The Titanic employed four; William Wright, William Crispin, Edward White, and Henry Wellesley Ashe. All four of them had signed on from the Titanic‘s sister ship, the RMS Olympic, where they had also served as glory-hole stewards. Of the four, only William Wright survived. Ashe and White’s bodies were retrieved by the Mackay-Bennett in their recovery operations but Crispin, if he was ever found, was never identified.

William Wright began his career at sea in 1887 and married in January 1888. The family would later move from Liverpool to Everton but without Wright who was, obviously, at sea for most of the year. He also maintained a separate address (probably as a boarder) in Southampton from where he joined Titanic in 1912. He survived the disaster in Lifeboat 13, the same boat that Lawrence Beesley inhabited and wrote about in his accounts of the night. But interest in him doesn’t end there.

Upon returning to England, he attended the funeral of Arthur Lawrence, one of the first-class saloon stewards. Lawrence had a similar life and career to Wright; they were both stewards, they both lived and married in Liverpool, and they both maintained a Southampton address separate from their families. Despite both working for the White Star Line, they don’t seem to have served on the same ships with any regularity, if they ever did beyond Titanic. Lawrence died in the sinking but his body was recovered and returned by the Mackay-Bennett, allowing him to be buried in Liverpool.

As a fellow survivor, Wright’s appearance generated some interest and he gave a brief account of the night as he had experienced it. Lawrence’s was the only funeral he attended and he claimed that while the two had never been intimate friends, they had served together for five years (something not borne out by their employment record) and he had always respected Lawrence. He was described as having been “deeply affected” by the loss and shortly after returned to sea aboard the Adriatic, incidentally Lawrence’s ship prior to boarding the Titanic.

If you’d like to join me for the behind the scenes research that went into this post, tidbits on the queer couples I discovered aboard the Titanic, or just more fun and games in picking apart history, you can support me via my Patreon.