Content warning: This post considers issues of sexual assault and child sexual assault.

In 1536, Henry VIII had his wife, Anne Boleyn, executed for adultery and treason. They had been married for only three years after a six year courtship that had turned the country on its head and forever changed the religious landscape of Europe. At the time, Anne was denounced as a whore and a traitor. She had seduced the king by devious means, including but not limited to; witchcraft. Once she became queen, she had humiliated and betrayed the king by having an affair with several courtiers, her brother among them. Her execution was celebrated by many at court and abroad. For generations, Anne’s name was practically a curse to the point that not even her daughter would speak it, even as she ruled England as its queen.

In recent years, historians have reconsidered Anne’s life and demise and have put forward a more sympathetic portrayal. For a while, Anne was the victim of her deranged husband who became obsessed with her even as she tried to deflect his advances. When he tired of her, he executed her so that he could move on to his next victim wife. Since then, history has settled into a more moderated view of Anne Boleyn. She isn’t the great whore who seduced a king into abandoning his wife and church. Neither is she a hapless victim who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, catching Henry’s eye just as he tired of his wife. Somewhere in the middle, we find Anne Boleyn; an intelligent woman who was able to take advantage of circumstances to elevate her position. Unfortunately, when courtly intrigue turned against her, she found herself on the executioner’s block, the victim of probably falsified charges as the king chose to rid himself of her.

Such treatment has not been given to Henry’s fifth wife, the second he had executed; Katherine Howard. Katherine was between fifteen and seventeen when she met forty-nine year old Henry VIII. He had just married his fourth wife Anne of Cleves to whom Katherine had been appointed as a lady-in-waiting. The marriage was short-lived. Henry and Anne were divorced six months later, and within two weeks of ridding himself of yet another wife, he married Katherine. They were married for sixteen months before Katherine was executed for adultery with slightly more cause than Anne Boleyn. But where Anne has been the subject of great interest and vindication, Katherine Howard is still condemned, almost five centuries later, and in some cases with greater vitriol than was aimed at her by contemporaries.

Doomed from the Start

The truth is, Katherine Howard was doomed from the start because she was, and had always been, alone. That might sound like a bizarre claim to make for a girl who was by all accounts surrounded by people for almost all of her life but she didn’t have a single person around her upon whom she could rely. In a court where factions and allies often determined whether a person lived or died, this could and would prove fatal. Catherine of Aragon could count on the likes of ladies like Maria de Salinas, who defied the king’s command and rode through the night to be with her mistress as she died. Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour, commoners like Katherine Howard, were supported (for the most part) by the great ladies of the king’s court and a retinue of family and friends. Katherine Howard had no such support.

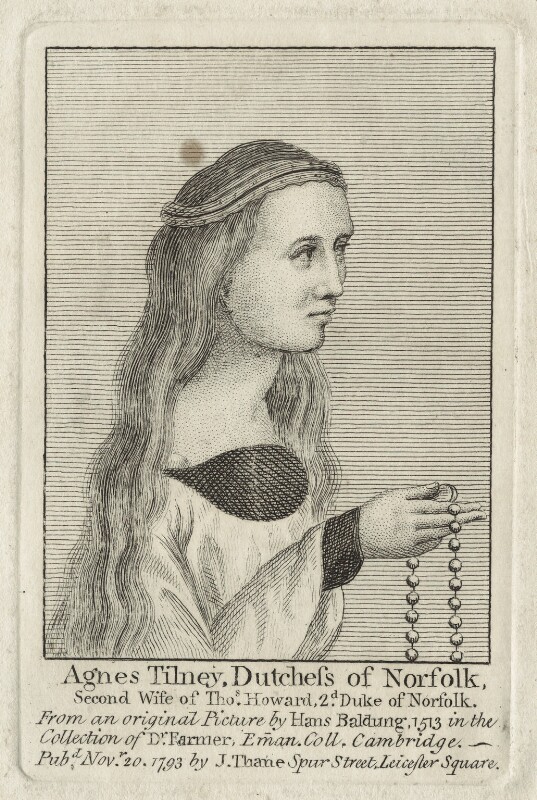

Around the age of five, Katherine lost her mother and her father, a compulsive gambler with little prospects beyond the Howard name he carried, had greater concerns than the care of his young family. Shortly after the loss of her mother, her father left for Calais, resulting in Katherine being separated from her siblings and sent to live with the Dowager Duchess of Norfolk. The Dowager Duchess had married Katherine’s Howard grandfather, the 2nd Duke of Norfolk, and had been prominent at the court of Anne Boleyn. At the time Katherine was sent to live with her, the Dowager Duchess’ household had become a practical school for the minor nobility and wayward Howard kin.

Katherine shared a dormitory with several other girls but supervision was lax. The Dowager Duchess paid little attention to the education of her wards and even less to their behaviour. Katherine was taught some skills to prepare her for a life as a gentry wife – the peak of what she could achieve given her station in life. While she might have learned how to read and write, she was hardly well-read. Her education was basic and barely touched upon the skills she would need to conduct herself at court, let alone as a queen. The Dowager Duchess herself wasn’t a continual presence at the household; visiting other houses or court instead, and when she was there, Katherine’s education likely didn’t even cross her mind beyond the tutors she had already employed for all her wards.

Katherine was, however, receiving a completely different education in the girls’ dormitory. The lack of supervision allowed the young men to visit the young ladies at night and liaisons were common. At this point, it feels pertinent to point out that even by Tudor times, Katherine was still a child, and the psychological effects of witnessing such rampant sexual activity in childhood have been studied by the medical community. A relatively common development in such children is that they demonstrate inappropriate sexual behaviour for their age. We won’t dwell on potentially diagnosing a woman who lived five hundred years ago on a history blog, but it feels like a pertinent observation.

Katherine’s first dalliance occurred when she was around twelve/thirteen years old. Her music teacher, Henry Manox, took an interest in her beyond his job. In one of her less controversial theories, Retha Warnicke, suggests that Manox groomed and abused Katherine which is borne out by Katherine’s later testimony that she had only submitted to Manox with the understanding that he would leave her alone afterwards. This is a relatively recent development, with most historians considering Katherine a willing partner to Manox. In fact, Katherine comes off as haughty and arrogant in her behaviour to him; suggesting that he was too low for her to ever consider marriage. Regardless of Katherine’s feelings on the matter, one servant recounted that the Dowager Duchess caught them embracing and was unimpressed, to say the least.

The Dowager Duchess had beaten Katherine, screaming that they should never have been left alone. The event clearly didn’t give her pause for thought; life in the ladies quarters continued as it had before. It also serves to emphasise just how little thought was given for Katherine. Elsewhere, the seduction of a pupil by an older teacher would have been a scandal that would have ruined Manox. But he continued to live and work at the Dowager Duchess’ pleasure but without Katherine as a pupil.

For Katherine, another romance followed two years later, this time with a great deal more enthusiasm on her part. Katherine was not the first attachment Francis Dereham had formed in the ladies’ bedchamber but it’s likely she would have been the last. The two were, by all accounts, completely committed and expected to marry even if their relationship had only existed for a few months. They called each other husband and wife, and had they married it would have been a reasonable coup for both. Katherine would have found a husband she evidently liked, one who had prospects and could provide for her. Meanwhile, Dereham would have gained the kinship of the Howards. However insignificant Katherine’s position within her family, her name was about the only thing she had to recommend her for a good marriage. The fact that nobody was thinking about Katherine’s future could have worked to their advantage. It was a sound union and it’s unlikely the Howards would have objected.

As it happened, the relationship was short-lived. Henry Manox wrote a letter to the Dowager Duchess informing her where and when Katherine and Dereham would meet which inevitably led to their discovery. Dereham was sent away to Ireland but he renewed his commitment to Katherine before his parting. By the time he returned to England however, Katherine was no longer at the household.

Towards the end of 1539, Anne, daughter of the Duke of Cleves, arrived in England to become Henry VIII’s fourth wife. The new Queen of England would require a household of attending women and Katherine was selected to be one of her ladies in waiting. She was not selected out of anybody’s desire for her to do well at court. Instead, the Duke of Norfolk visited the Dowager’s household, had all the Howard girls put on display, and selected the prettiest one to attend the new queen; Lucky Katherine Howard.

While Katherine was not placed in the queen’s household with the intention of seducing the king, the opportunity soon presented itself. Not that Katherine herself had much to do with the act of seducing him. Henry did not like his wife but he did like Katherine. The Dowager Duchess was called to court to educate Katherine on how to behave that she might best please the king. The Duke of Norfolk handled any other arrangements, Henry showered her with gifts, and Katherine’s own thoughts have been lost to history, assuming she was allowed to have any. A divorce from Anne of Cleves was secured, the orchestrator of the marriage Thomas Cromwell attainted for treason, and the path to Henry’s fifth marriage was clear. Henry and Katherine were married eight months after her arrival at court on the day of Cromwell’s execution.

Little Katherine Howard was now Queen of England, and it’s safe to say that she had no inkling as to what that actually meant. She wasn’t an idiot, unaware of the world around her, but she had barely been raised to a courtly life let alone with the ability to rule over it. She had barely been raised at all. Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour had been commoners but both had been strong women in their own right. Katherine lacked the education and the spirit to follow them, not to mention the fact that she was still a teenager.

The Dowager Duchess had given her scant instruction on how to please her new husband but was hardly a solid and guiding presence in Katherine’s life. Katherine’s household was equally unreliable. Her ladies were mostly made up of the girls of the dormitory she had grown up in, most of whom had blackmailed their way into the position by trading on the knowledge they had of Katherine and Dereham. It was a dangerous situation for a queen, let alone a queen married to a man with such a history as Henry. She had been left to grow up without any attention to her person or character and now, still a teenager, there was nobody to guide her on how to handle her elevation to the highest position a woman could hold in the country. There was certainly nobody to warn her of the indiscretions of her youth.

Katherine’s father had died shortly before her court debut, not that there is anything to suggest he would have been in any way a positive influence on his newly royal daughter. Her father was however her closest relative and without him, she was supported entirely by a loose faction of relations who were keen to exploit her position for all potential rewards. Her situation had been almost entirely engineered by the Duke of Norfolk and his followers who were looking to overthrow the King’s advisor, Thomas Cromwell, and establish themselves as the leading faction. Katherine was a means to an end but none of them were actually invested in her success beyond providing a potential heir which would have solidified their positions.

At some point, Katherine’s eye was caught by one of the king’s favourite courtiers, Thomas Culpepper. They were both surely aware of the consequences of a potential affair but that didn’t stop them. Not that she should have needed it, but Katherine had nobody to keep her in check or remind her that she was putting her life on the line. Quite the opposite. Her chief lady-in-waiting, Jane Boleyn, Lady Rochford, was active in arranging the affair.

Lady Rochford was the wife of George Boleyn, the brother of Anne. It was accusations of incest and adultery that had sent them both to the block and the jury is still out on whether it was Lady Rochford’s own allegations that condemned them in the first place. Arguably, she knew better than anyone what rumours of adultery could do to a queen, but that didn’t stop her from arranging Katherine and Culpepper’s illicit meetings and running messages between the two. She was also the most senior lady in Katherine’s household and while she can hardly be held responsible for Katherine’s behaviour, she could have put an immediate stop to it. She didn’t.

Despite their surroundings and the constant eyes at court, the affair was not discovered in a conventional way. Far from the queen’s household, a minor gentleman, John Lassells, berated his sister Mary for not securing a position among Queen Katherine’s retinue. In response, Mary, who had grown up in the household of the Dowager Duchess, told him that she had no intention of working for a woman of such loose morals. It’s thought that Mary Lassells had, in fact, tried to gain such a position but had been rejected, something she probably wasn’t about to tell her brother. When pressed, however, she revealed a number of Katherine’s indiscretions.

John Lassells was now in an impossible situation. He was associated with Archbishop Thomas Cranmer’s faction which opposed the Howards, and such information would certainly promote their interests over their rivals. On the other, he was a minor courtier who lacked the support needed to take on the powerful Howards. He could pretend that he hadn’t heard a thing and was ignorant, sweeping it under the rug, but if it later came out that his sister had known and in turn told him, then he was complicit in a conspiracy against the king. At best that could send him to the Tower, at worst it could lead him to the block. Ultimately, he decided to pass the buck. He told Archbishop Cranmer everything he knew and made it the Archbishop’s problem.

I feel that Lassells’ fears were entirely validated when the Archbishop himself feared to tell the king what he knew, terrified of reprisals. He wrote a letter that detailed Katherine’s alleged activities and left it where Henry would find it. Henry was surprisingly calm about it all. He ordered an inquiry into the allegations with the sole intention of disproving them.

The queen’s ladies-in-waiting were gathered individually to be questioned and did exactly what you would expect of a group of young people with no particular loyalty to their mistress and supposed friend. They told the delegation everything they knew and then some. Dereham was interrogated for his involvement with Katherine which in turn led them to Culpepper. What had started as an attempt to disprove malicious gossip regarding the queen’s youth had revealed a much more recent indiscretion.

Lady Rochford revealed her part in the affair and Katherine herself completely broke down in the face of questioning. But there was some question over what crimes, if any, Katherine had actually committed. Whatever she had done with Dereham and Manox was a scandal but not criminal. If she had married or been pre-contracted to Dereham then her marriage to the king was invalid which was again, not a criminal act. The only crime on the cards was adultery with Culpepper but there was no proof that the two of them had actually slept together and the two denied ever going that far. So many Howards were imprisoned in the Tower of London that the Royal Apartments had to be opened up. Dereham and Culpepper were tortured but still nothing could be proved.

The king, however, had determined that Katherine was guilty of treason, therefore there had to be something to charge her with to fit the punishment he had already fixed on. Dereham and Culpepper were executed, the latter for intent to commit adultery. Katherine was also condemned for the presumption of adultery. Added to this, the law was changed making it treason to conceal the sexual history or lack of virginity of a woman that the king intended to marry. Katherine was therefore retroactively guilty of this extremely specific law, as were several of the Howards and Lady Rochford. Most of the sentences were commuted though Henry had to be convinced to spare the Dowager Duchess who he considered one of the prime offenders. From this point on, nobody could champion a lady to become Henry’s wife without disclosing her sexual history. Incidentally, after this law was passed, the days of courtiers vying for favour by pushing a young lady under the king’s nose ended quite abruptly. Had they promoted the interest of a girl who was then determined to have lied about her virginity, everyone involved would have been condemned for treason.

On Monday 13 February 1542 Katherine was led out to the Tower Green where, after a short speech, she was executed. The oldest she could have been is twenty but in all likelihood, she was still a teenager. Stories circulated that she told the gathered crowd that she’d prefer to die Culpepper’s wife than a queen, but these were just stories. Her final words followed the convention of the day. They were contrite and praised the king before committing her soul to God. After her body had been moved aside, Lady Rochford who had been brought down with her, laid her head on the same block and minutes later was also dead.

Katherine was taken to the nearby church of St Peter ad Vincula where she was laid to rest beside her cousin Anne Boleyn. And really, that should have been the end of her story.

Doomed from the End

In her life and long after her death Anne Boleyn was the Great Whore. Katherine Howard however managed to escape such censure. One ambassador described her as a ‘common harlot’ but while she was considered a scandal, contemporaries were quick to move on from her. Modern historians, however, have been far more vicious in their assessment of her. Prepare yourself for some really interesting takes.

In his book, Tudor Queens of England, David Loades suggests that Katherine was only unfaithful because she wasn’t sexually satisfied with Henry. This is put across in his chapter ‘The Queen as Whore.’ For Alison Weir, she was “an empty-headed wanton”. For Julia Fox; a difficult and scheming woman who ensnared a vulnerable Henry, and to David Starkey, she is “a silly little slut.” In the interests of balance, one of the kindest interpretations comes from Antonia Fraser who suggests Katherine failed to grasp the seriousness of the role she had been elevated to which paired badly with her natural naivety. More recently, Conor Byrne reconsiders Katherine’s reputation and questions the impact popular media has had on her image. However, for the most part, we are given assessments much like this;

Modern interpretations of Katherine seem to be coloured by the idea that she deserved her punishment. No grace is extended to her on account of her age or situation. She should have known better and therefore is fair game to be dragged hundreds of years after the fact. But the above tweet demonstrates the much more casual and insidious misogyny that is inflicted on Katherine. The language used to describe her is often violent. Granted, not as violent as having one’s head chopped off, but words like ‘slut’, ‘scheming’, ‘wanton’, and ‘whore’ are insults more than they are descriptive.

Much has been made of the fact that Katherine was only interested in fashion and jewels as if that is proof that she was so frivolous as to be unsuited to the role of queen. It’s true that her royal husband showered her with gifts and Katherine relished in them. But it’s also true that this would have been the only time in her life she would ever have received such gifts. She had gone from being an inconvenient orphan to Queen of England. She likely had never seen such expensive things until she had come to court. Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour were given similar gifts and took as much care with their appearance as Katherine did, but they have been deemed fashionable by history.

She had no interest in politics and even if she had, she was too young to participate. But this is also held against her. She wasn’t particularly educated so didn’t patronise intellectual pursuits. Instead, she liked dancing and music and without anything deeper to balance this, she is seen as entirely frivolous. This lack of interest in anything besides being youthful and gay is one of the things that attracted Henry to her. He wanted a young, pretty wife that he could spoil. He got a young, pretty wife that he could spoil, and after her execution history condemned her for being little more than a young, pretty wife, spoiled by her husband.

It is Katherine’s youth that inevitably counts against her. She has been deemed to be a silly little girl, which in most ways she probably was, but it doesn’t follow that she deserved to die for it. That she acted foolishly is undeniable, that she grasped the implications is debatable, but where Anne Boleyn has emerged in history as Henry’s great victim, Katherine seems to have taken her place as the truly Great Whore. Historians have spoken of her with far greater condemnation than Katherine’s contemporaries ever did.

If you’d like to join me behind the scenes for stories that didn’t make the post and other historical tidbits, you can support me via my Patreon.